The Architecture of Hellfire Romeo: Drone strike in Miranshah, Pakistan 2012

The Architecture of Hellfire Romeo: Drone strike in Miranshah, Pakistan 2012

London-based studio Forensic Architecture represents an entirely new field of practice. Using open-source data and 3D design tools, its team painstakingly reconstruct sites of conflict to produce damning evidence of human rights abuse. What began as an academic exercise has become a powerful new way of analysing the world, writes Alice Bucknell

It’s a drizzling winter evening in south London; the Richard Hoggart Building at Goldsmiths College is almost totally deserted, its students having ditched the premises for cozier pub surrounds. A lofted classroom on the second floor remains illuminated as its dozen inhabitants concentrate wordlessly on their flickering screens. A bowl of tangerines in the centre of the room offers the only splash of colour in this white-on-white world, save for a dry-erase board with current clients-cum-collaborators listed in sharp green, and an unintelligible piece of cartography – not quite a metro map, nor timeline in any traditional sense – stretching across the opposite wall. Welcome to the Forensic Architecture Studio.

Forensic Architecture (FA) is a multidisciplinary agency based at Goldsmiths, University of London, that intends to rewire the discipline of architecture as a socio-political tool. The team uses investigative research methods and architectural thinking to split back open and re-assess international human rights violations either misjudged or ignored entirely by governments, police, the military, and corporations. Working collaboratively with NGOs like Amnesty International as well as human rights lawyers, FA stakes its claims by using open-source metadata gleaned from social media and the internet at large in order to produce damning evidence that upends previous investigations. It’s a process that director and founder Eyal Weizman refers to as ‘counter-forensics’.

![]() The Forensic Architecture team at work in Goldsmiths in London

The Forensic Architecture team at work in Goldsmiths in London

‘Forensic Architecture began in 2010 as a totally academic project,’ research coordinator Christina Varvia explains when I ask about the collegiate digs. A year later, Weizman, an Israeli architect and academic, received a four-year, €1.2 million (£1.1 million) starting grant from the European Research Council. The Left-to-Die Boat case, in which 63 migrants lost their lives while left to drift for 14 days in NATO’s maritime surveillance area at the height of the 2011 war on Libya, was among FA’s first hardcore applications of its process to potential crimes against humanity and remains one of its most powerful works to date. The report produced by FA subverted NATO’s own surveillance technology to transform the available data into evidence of the participating states’ awareness of the migrants adrift at sea. The report has since formed the basis for a number of ongoing legal petitions for the crime of non-assistance led against NATO member states.

‘When the grant ran out in 2015, we switched gears into a research agency, working to secure independent funding and commissions from NGOs, museums, and other collaborators,’ says Varvia. She doesn’t mention the ERC’s grant renewal in 2016, but it explains the ongoing connection with Goldsmiths, through which FA qualifies for the award and ‘through which we’re technically employed’. Since 2016, the parallel universe of Goldsmith’s Center for Research Architecture has offered an MA stream in forensic architecture, wherein future forensic architects can cut their teeth on the burgeoning discipline while their tuition fees help to prop it up.

After a joke about unpaid internships that doesn’t go down so well, we emerge from the murky waters of institutional a liation to talk about FA’s larger missive in the elds of human rights and non- governmental activism, as well as pushing against the boundaries of architecture itself. I learn that their use of ‘forensic’ doesn’t relate to the common understanding of forensics as the use of scientific methodologies in the investigation of crime. Instead, its use here stems from the etymological origin forensis (Latin for ‘pertaining to the forum’): a nod to the ‘multidimensional space of politics, law and economy’ in the Roman forum. Staying true to its heterogeneous origins, FA’s current roster – a core team of around 11 that expands and contracts to fit the bill for the project at hand – is a diverse crew of ‘architects, filmmakers, journalists, graphic designers, and artists’, says Varvia, gesturing around the room as she moves down the laundry list of specialisations. ‘Having all these different practices involved is essential,’ she says with a small smile. ‘I can’t imagine it working any other way.’

With so many skill sets converging beneath an outer coating of International Art Speak PR that would make anyone unfamiliar with media aesthetics and spatial theory go cross-eyed, it can be difficult at rst to decipher the pedestrian value in FA’s work.

‘We are not service providers, or graphic designers,’ Varvia says simply of the practice. ‘We work to see how the material already out there can be revisited and reimagined by the individual witnesses.’ Still, there is an electrifying potential underlining this effort to decolonise architectural thinking – a type of ‘architecture in reverse’, as Weizman calls it. Beyond architecture, FA’s work is an open call to reassess how we analyse the world, and the means through which we recognise such a thin threshold of ‘legitimate’ information distributed through it.

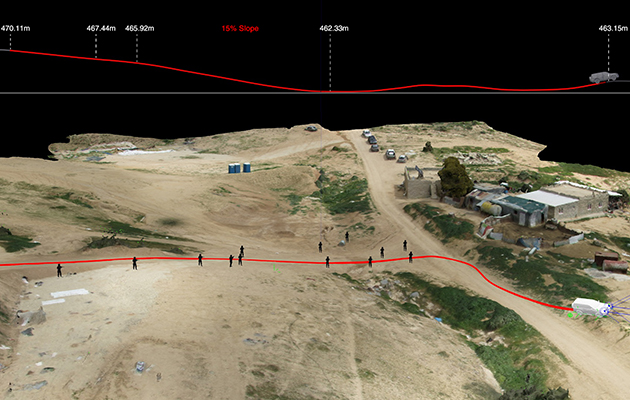

The Umm Al-Hiram project investigated the killing of a Beduin man and a policeman in Negev in 2017

The Umm Al-Hiram project investigated the killing of a Beduin man and a policeman in Negev in 2017

Despite the emerging discipline’s avant-garde ambitions, joining the ranks of FA requires just as many academic and professional qualifications as a traditional architecture studio; several team members come from past stints in large practices, which ‘helps with the deadline crunches or occasional overtime shift to see a project through’, architect and researcher Nicholas Masterton tells me over a pint later that evening. With a track record that includes Wilkinson Eyre, Masterton is no stranger to juggling four or five projects at once, but notes a key difference at FA: ‘I feel for the first time that my work matters.’ Perhaps boosted by the collegiate setting, there’s a palpable camaraderie among the group, who typically go out for drinks together after a long day of ghting police suppression and state-supplied cover-ups.

As FA moves out of academia and into an increasingly commission-led, project-based approach, its stage presence has dialed up dramatically. In recent years, FA has appeared at international art and architecture biennales including the 2016 Venice Biennale, Reporting from the Front, curated by fellow activist-architect Alejandro Aravena, documenta 14 in 2017 in Kassel, and the Istanbul Design Biennial in 2016, as well as key exhibitions in Mexico City and Berlin. Most valuable, it seems, are the countless lectures delivered by Weizman, who seems to be on a perpetual world tour (he was giving a week-long series of talks at various US institutions when I visited the studio). ‘We consider each exhibition to be a fundamental aspect of its related case,’ Varvia says, defending the strategic and symbolic significance of their institutional presentations. ‘It would be problematic if we were simply doing it for exposure, but each exhibition performs a political role.’

This sentiment is echoed by long-term FA collaborator Andreas Schüller, who directs the International Crimes and Accountability Program of the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR). Schüller, who has worked with FA since 2010 on cases from Guantanamo to Germany, recalls the painstaking process of reconstructing a crime scene within a basement room of the Haus de Kulturen der Welt (HKW) as part of 77SQM_9:26M – one of FA’s most significant and widely exhibited projects. ‘For us, it’s incredibly powerful, because we are mostly lawyers whose work never leaves the printed page,’ says Schüller. ‘The law is only one component of each case; it needs to articulate and make accessible the broader political context of this violence.’

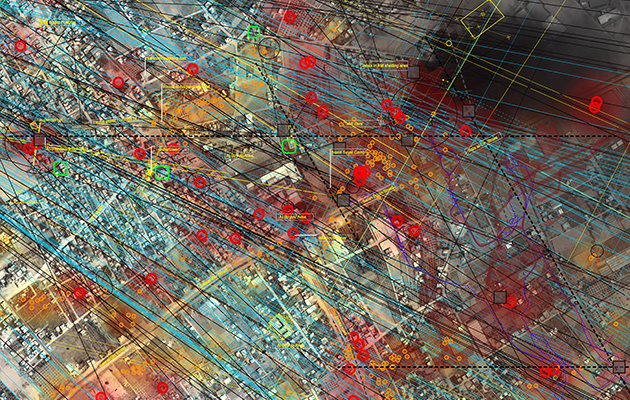

A still from an animation of eastern Rafah, in 2014, marked with air strike and artillery craters

A still from an animation of eastern Rafah, in 2014, marked with air strike and artillery craters

Stationed just a few hundred yards from the German parliament in Berlin’s HKW, FA’s crew of smell specialists, sound experts, architects and cameramen convened to recreate the 2006 murder of 21-year-old Pakistani Halit Yozgat by the neo-Nazi group NSU inside his family’s internet cafe in Kassel. A member of the Hess secret service, Andreas Temme, was present in the cafe at the time of the crime, but claimed ignorance. Through a detailed restaging of the murder, FA aimed to prove beyond reasonable doubt that Temme would have heard the gunshots, and not only seen smoke, but also Yozgat’s collapsed body behind the counter upon exiting the cafe, effectively countering Temme’s testimony. This data was presented and made publicly accessible within a 68-page document produced with the help of the ECCHR, while the HKW served as home base for a parallel public programme that saw the project collaborators joining forces to bring Pakistani civilians tied to the victim’s family to Germany for screenings and symposiums.

According to Schüller, all of the investigations and exhibitions they have collaborated on – from a torture case at the Saydnaya Prison in Syria in 2011, to a factory fire in Karachi, Pakistan in 2012 – go beyond a mere pedagogical exercise, allowing for witnesses and survivors whose testimonies were previously batted aside to have their suffering acknowledged. ‘It is an opportunity for them to open up and nally receive some form of closure,’ he suggests when I ask after the ethics of what could be read as exhibiting the trauma of survivors. ‘There are, of course, potentially damaging e ects triggered by this process of walking the victims through the traumatic event’s restaging, where they may recall previously suppressed key details that will bring forward the case. It’s a very emotional event, but it also has the possibility to be an extremely healing one.’

So what does this new discipline of architect-led activism centred around civilian data look like? ‘We don’t have access to our field sites in the way that traditional forensics operate, from the field, to the lab, to the forum or trial,’ explains Varvia. ‘Instead, we listen closely to the situated knowledge that states ignore, and we work closely with NGOs and other groups embedded in the local context to carry out these investigations.’ On FA’s watch, this roughly translates into mining the digital commons of the internet for potential evidence, extracting and repurposing it through the team’s fluency in specialised design software from Rhinoceros 3D to Adobe Premiere Pro 2018.

FA is currently showcasing its process in the exhibition Counter-Investigations: Forensic Architecture at the ICA as a sort of ‘forensic architecture 101’ featuring 12 deconstructed case studies and a public programme of events. Eager to learn more about this process myself, I end my visit with a quick lap around the studio to scope out some of the practice’s current projects. ‘Sometimes we don’t even have images,’ a young freelance designer explains while showing me FA’s evidence from an ongoing case in Negev, Israel. Using satellite footage combined with a leaked audio clip, FA proved that a runaway driver murdered by police did not intend to drive into a swarm of police cars, but was shot in the knee while his foot was on the gas pedal. He points out the precise moment of shooting before the car lurches down the hill.

FA’s investigation into the seizure of the Iuventa, am NGO rescue vessel in the Mediterranean in 2017

FA’s investigation into the seizure of the Iuventa, am NGO rescue vessel in the Mediterranean in 2017

Proven where? I ask. The designer hesitates, shrugging slightly: ‘Well, not officially.’ The most ambiguous part of FA’s work remains how and where it can be used. Working with an entirely different understanding of what constitutes evidence, it’s perhaps unsurprising that the biggest challenge to FA – beyond the issue of funding – is having its evidence recognised within the court cases and international tribunals that its collaborative prosecutors serve. For now, publishing findings online and exposing corruption through digital activism remains its primary tactic.

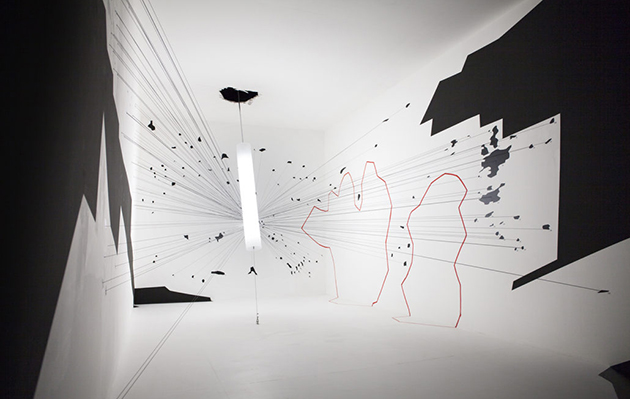

It’s also important to underscore just how different their working methodology really is. Another designer shows me a video recreation of a civilian drone strike in Gaza in 2012: one of FA’s most hyped cases. Presented in model format at the 2016 Venice Biennale, the flight path of the drone’s explosion – shown as a sort of star cluster in the video, and an elaborate series of strings at the Biennale – and the absence of damage to the wall suggests that bodies in the room absorbed the shrapnel shards. At its most simple application, FA’s work is about reframing value. It’s a parallel universe where the lack of information is merely a different type of information, and is as powerful as more conventional visual evidence. This process involves a logical leap into what Weizman calls the ‘threshold of detectability’ that dismantles the bias towards immediate or obvious evidence.

Exalting the unrecognised evidence of shadow clocks, dust clouds, debris sprays, smoke plumes and other ‘metadata’ extracted from low-res image uploads and illicit geotagged Tweets that somehow slipped through the system, FA is after nothing less than a total systemic overhaul of how we do architecture, and to whose benefit. There’s something fantastical about its practice, too, in using architecture as a time capsule that can effectively re-open misjudged human rights violations of years past, through an investigation of the investigation process.

‘The ICA is intended to be a homecoming,’ Varvia says of the show, a flicker of pride – and relief – in her voice. It is true that FA has exhibited far and wide alongside its cases, but this sort of exhibition, where it can reveal its process instead of (strategically) stirring the drama pot as part of the case at hand, is a relatively new a air. And a wholly necessary one, for the practice to elope from the hallowed halls of academic architecture’s armchair activism and become truly accessible to the public it serves.