|

|

||

|

Yes, the opening of the Design Museum is a significant achievement, but this is not how museums should be made or our buildings conserved – it leaves both culture and architecture diminished The west end of Kensington High Street has always been a struggle, weighed down by 1930s apartment blocks that menace occupants and passers-by alike. Despite the glamorous location, their brick mediocrity has long ensured a reputation as final redoubts for actors and prostitutes. Now, courtesy of a far more venal profession – the property developer – a new Design Museum nestles in their midst, constructed beneath the remnants of the most important piece of public architecture of the post-Festival of Britain era: the Commonwealth Institute (RMJM, 1960–62). The purchase of the Commonwealth Institute’s covetable site in 1958 and its consequent construction were paid for out of the public purse, so how did they end up in the hands of arch-developer Stuart Lipton – then of Chelsfield Partners – who reportedly paid a mere £4.32 million in 2007? Today, that sum would barely procure you a two-bed flat in the three gleaming new residential blocks that now hug the Commonwealth Institute’s main exhibition hall in a clumsy embrace. To allow the construction of this £120-million ‘Hollandgreen’ development, the Institute’s original gallery and administrative wings were swept away by the developers, as was its rare modernist landscaping.

The Design Museum seen from Kensington High Street through Hollandgreen (2016) The behaviour of Chelsfield has been depressing but predictable, as has that of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, given their desire to bring investment to an area sapped by the opening of the Westfield shopping mall in nearby White City. More dispiriting is the willingness of lead architects OMA and, to a lesser extent, the Design Museum to collaborate in this exercise in profiteering. Their architectural and cultural prestige has lubricated the project’s laborious passage through planning, and for what precisely? The architects have, at long last, their first major London project. The museum has a 175-year, rent-free lease on a ready-made, spacious landmark, albeit in an iffy location, as well as £20 million of funding in kind. And what does London gain? Even by Kensington & Chelsea’s low standards, the residential offering – 54 bland luxury apartments (one at £23 million) with no affordable component – is a sharp slap in the face. OMA partner Reinier de Graaf offers elaborate explanations of the conceptual complexity of these three new ‘discreet servants’, yet this is hard to square with their highly familiar language of burnished residential luxury, lifted in large part from Swiss cityscapes, complete with sequenced windows and occasional voids and protrusions. He asserts that this appearance ‘registers the amplitude of the [Commonwealth Institute’s] roof’s curvature like graph paper’. The claim is curious, as the three solid, shining rectangles render the subject of this supposed tribute invisible. Twisted 45 degrees from the street, they ‘align with the exhibition hall’, maximising light for interiors yet obscuring views of the Institute (bar that from the north, which, ironically, remains compromised by the same wall that frustrated the original architects in their pursuit of the ‘tent in the park’ concept back in 1960). Two cutaways shelter a private lobby and a forbidding route through to the museum via retail. Security barriers and cameras remain firmly in place. A swimming pool, gym, golf simulator, garages and other tasteless badges of gated life are buried beneath OMA’s new ‘romantic landscape’.

OMA’s Hollandgreen (2016) with Troy Court in the background But why should we care about the survival of the Commonwealth Institute anyway? Didn’t it exemplify the polite, gutless mediocrity of the ‘New Elizabethan Architecture’, neither Saarinen nor Smithson? Where is Brutalism’s social urgency? Wasn’t it just some cheap, post-Imperial propaganda project, built literally from the copper, hide and timber of ex-vassal nations? The interior design, with its gestures towards equality, merely mirrored the Commonwealth’s inept political attempts to preserve Britain’s influence by alternative means. Compare the few despairing efforts from the Twentieth Century Society advocating the deeply unfashionable cause of the Commonwealth Institute to the barrage of breast-beating about Robin Hood Gardens, Birmingham Central Library and countless later projects, and it’s pretty clear no one really did give a toss. But we should have done. The Commonwealth Institute’s hyperbolic paraboloid roof – in many respects unique, in part a result of the recourse to a pair of stockings to provide its form – may still stand, yet the listed modernist building beneath has been ripped out and replaced in its entirety, bar a few 1960s knick-knacks secreted here and there with an air of mild embarrassment. Initially, Kensington & Chelsea and the Commonwealth itself, keen to maximise proceeds from a crumbling, leaking white elephant, tried to raze the entire site. They failed in this ambition thanks to the Grade II* listing dating back in 1988 but, in a highly unusual turn of events, succeeded in 2005 in persuading English Heritage that the listing be altered to indicate that the ‘primary interest’ of the site related to the exhibition hall and that the administrative wing was of ‘lesser interest’, demonstrating a desire at high levels of government to hasten proceedings.

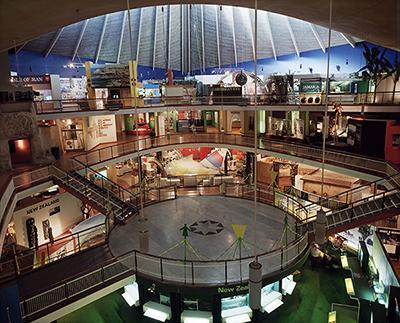

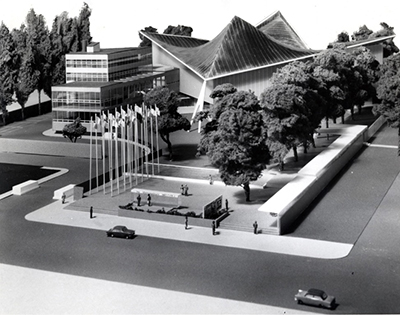

The Commonwealth Institute’s hyperbolic paraboloid roof today From 2007, huge resources were successfully thrown by new owners Chelsfield into proving that the entire heritage of the site was invested in that concrete-and-copper roof alone. The role of the modernist garden designer Sylvia Crowe, known for her work at Harlow and other new towns, in the English Heritage-listed gardens was aggressively minimized. Even today, de Graaf dismisses this elegant landscape with a knowing smirk as ‘essentially a carpark’, despite widespread respect for its covered ceremonial route, past flagpoles and over a mirror pond, that led directly into the centre of the exhibition hall. Similarly disparaged was the original interior by Peter Newnham and Roger Cunliffe, a heady atrium with circular balconies and a central dais, hailed in 1962 as an ‘immense and obvious success’ by the Architects’ Journal (which was rather less fulsome when appraising the roof). The ‘cheap’ and ‘uninviting’ textured glazing of the Commonwealth Institute’s opaque facade and its ‘prosaic’ wings were continually belittled in planning submissions, which also offered broken promises of increased public and green space, and of a ‘more positive relationship with Kensington High Street’.

The interior of the Commonwealth Institute by RMJM, photographed by Martine Hamilton Knight of www.builtvision.co.uk in 1989 Today, all parties – architects, developers, museum and local authority – readily proclaim the line that the final result is an unmitigated blessing, glorying in their achievement of ripping out all but that fragile concrete roof. Their basic premise is that only by ‘liberating’ (OMA’s own term) the roof from its dour 1960s reality could this copper and concrete expanse truly be revealed as an icon of modernism, isolated from anything that might suggest its historical or physical context. De Graaf, who expounds the ‘improvement (or even correction) of a given context’, appeared particularly pleased with himself at the opening as he stated that ‘dead sites and listing go hand in hand’. Yet the result is a shell. History has been scooped out from under the famed hyperbolic paraboloid, which drew on the pioneering concrete shell structures of Mexican architect Félix Candela in a frail yet understandable attempt to look beyond European architecture in recasting Britain’s contested role in a postcolonial world. It was just one element of an exhibition hall designed to express renewed optimism about the potential of technology, science and mutual understanding to improve society. Its demolished wings may have been clad in austere engineering brick, but they were appropriate in scale and material, housed an admired art gallery and cinema, and existed in an effective, forceful relationship with the main exhibition hall – in short, they were everything that the incongruous, slick Hollandgreen is not.

RMJM’s model of the Commonwealth Institute with additional wing in 1959

The exterior of the Commonwealth Institute by RMJM, photographed by Martine Hamilton Knight of www.builtvision.co.uk in 1989 Terence Conran describes the Design Museum’s new atrium as a ‘cathedral of design’, yet its predecessor was far richer and more revelatory. John Pawson, chosen as the ‘gentlest’ option for the insertion of this new interior within an existing structure, has designed an angled construction in immaculate yet inert oak. Strangely, he compares it to an open-cast mine, but in reality it is one more white cube, the hackneyed option for forced marriages of culture and commerce. Additional levels have been added to house three display spaces (none huge), an auditorium, educational spaces, a cafe, shop and restaurant, members’ and residency spaces, offices, an archive and more. 10,000sq m of ‘modern museum’ have been tightly squeezed under a roof originally designed to house little more than half that. Ironically, the original Commonwealth Institute, with its additional wings, had over 12,000sq m at its disposal, and boasted many of the same facilities. Those were different times. The inevitable result of this overloading is not gentleness, but an overbearing bulk that both contradicts and conceals much of the roof’s famed curves, hiding or anaesthetising what it purports to reveal. Lacking any focal point, the atmosphere feels more educational than uplifting – its predecessor, long mocked as a hangout of school trips, at least transcended its role.

John Pawson’s new atrium for the Design Museum (2016) So, the diminished roof is, as intended, the sole architectural gesture left on site, sheltering a glossy new structure – part-replica, part-revamp – underneath, pimped up with shiny transparent glazing to maximize event revenue and wow factor at night. It’s hard to feel that anyone comes well out of this act of ‘conservation’. The architectural press, with the occasional noble exception, has retreated into polite equivocation to avoid offence and inconvenience. Heritage bodies are left licking their wounds. Simon Thurley, their voice in government at English Heritage from 2002 until 2015, has confirmed his long-standing reputation as a lukewarm advocate of 20th-century architecture, proclaiming the transformation of the Commonwealth Institute a ‘successful conclusion’ – even, worryingly, a precedent. Apparently, modernist architecture must embrace radical transformation to overcome popular hostility, preserving ‘overall idea and significance’ rather than historic fabric. If introducing a new museum into an existing museum structure requires the latter’s gutting and the sale of all its public land, it seems we must celebrate this outcome. One can only wonder how Thurley feels more significant changes of use should be handled. One historical parallel might be the Queen’s Tower in South Kensington – the sole remnant of the Commonwealth Institute’s predecessor, the Imperial Institute, whose demolition lead directly to the foundation of the Victorian Society. Yet the Commonwealth Institute was all the more precious for being so much rarer. Given its historical context, it was indeed flawed and cheaply built, but that very context is a key part of the reason it was originally listed. More, it employed built form to express the architectural, political and social aspirations of its time. The glistening, crystal now standing in its place also speaks of its time, highlighting the Faustian monetary pacts that are involved in museum-making and architectural practice today. Highlighting post-Imperial sins may be a congenial means of virtue-signalling, but our own era has a great deal to answer for, and that is where we should concentrate our attention.

The construction of the Commonwealth Institute (1960–62) So now it is left to the Design Museum to fill the new structure with meaning. ‘Design’ has become a grandiose term, all-encompassing in remit and ambition. This does provide wide scope for exhibitions, hopefully ensuring the Design Museum’s viability in its challenging new location, as long as installations of design art do not proliferate. The initial exhibition, Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World, does not bode well in this regard, tending towards jargon, video work and insular navel-gazing of the sort that is hardly ideal for a museum pronouncing its desire to ‘move in from the margins’, be a ‘mainstream part of the conversation of the world around us’ and, incidentally, attract 650,000 visitors a year. Yet a degree of stall-setting for design’s expansive new era is understandable, and thankfully the future programme looks significantly more concrete. Of greater concern, given director Deyan Sudjic’s brave intent that the Design Museum become ‘a world-leading creative centre for design and architecture’, is the casual, destructive disregard that has already been shown for previous generations of practitioners on the site. The project deserves to succeed – mountains have been moved to bring it to pass – and we should wish it well. But it will always be tinged with a certain sadness. This is not how museums should be made, nor how buildings preserved, but these two ambitions have been ruthlessly crunched together at the behest of real-estate profits, because we are no longer willing or able to fund either of these goals from the public purse. If anything, the new Design Museum is a sharp reminder that the narcissism of starchitects and the expansionism of design advocates remain essentially powerless against the political and economic forces now shaping our cities. For an interview with the Design Museum’s director Deyan Sudjic, see our January issue, Icon 162 |

Words John Jervis

Above: The newly transparent Design Museum today

Images: Design Museum/Luke Hayes; OMA/Sebastian van Damme; Design Museum/Hélène Binet; Martine Hamilton Knight/Builtvision – image sourced from www.builtvision.co.uk – RESPECT COPYRIGHT; Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea; Allies and Morrison |

|

|

||