|

image: Maja Flink |

||

|

Conversation between architect Francois Roche and graphic novelist Warren Ellis, moderated by blogger Geoff Manaugh, at the Architectural Association, London, 29 May 2009. Geoff Manaugh François, maybe you could say a little about how you work with a client, and Warren, I want to ask you about your relationship with an illustrator. Francois Roche We know that it’s a lot of work to write a story. And it’s exactly the same with a client, it’s a lot of work. When a client comes to me I have to understand what he wants exactly and I will then filter his desires. We need to extract a lot of information: the sexuality of the client, the situation – political, sociological, chemical, ecological or ecosophical. So when you start a book you start by embracing the complexity, and step by step from the complexity something grows. Warren Ellis As a writer of graphic novels, what I’m producing is a complete blueprint for the work. A full script describes every panel, one by one, laid in a dialogue, that’s just the working document. Obviously it turns into comics from the script. Comics are such a weird bastard hybrid form anyway. Comics are cartoons, they’re political cartoons, they’re theatre, they’re T-shirt slogans, they’re film to an extent, they’re just eight or nine things that have been glued together to form this bizarre 20th-century art form. So yeah, the relationship with the illustrator is peculiar and hard to define because they’re not just a hired hand, there is a very particular skill-set to comics art that you don’t really get in any other narrative art form. GM As a layman, architecturally speaking, what goes through your mind when you see François’ work and hearing him talk about it? Is it exciting? Is it potential material? WE As with any theory, it’s fascinating to me. It’s absolutely material. People always ask me as a writer where I get my ideas from and it’s quite simply this: I take in as much information as possible from as many different places as possible and place it in the compost bin in the back of my head and it will eventually rot down and at the bottom there’ll be one piece of data that will plug in to the second piece of data and that’s the germ of the story. GM Actually, where don’t get your ideas from? Is there a place that you want to avoid … WE As a writer you have to go everywhere for your information. What you do avoid is certain writers and certain forms of writing. When I’m very, very deep in writing fiction, I won’t read fiction. And there are some writers whose styles have very strong flavours, they’ll affect your style just by reading them. Stephen King uses the metaphor of “you don’t put that in the fridge because it’ll flavour the milk”. With King it’s Ellison. If he reads a lot of Ellison he starts writing like Ellison. [For me it’s] Hunter Thompson and Jack Kerouac. GM I look at buildings as how they present possible narratives. I interviewed Patrick McGrath, a British novelist who writes gothic stories, so there’s a lot of foggy moors, old castles, abandoned houses, attics that no-one goes into … but then the question is: is there a setting in which Patrick McGrath could not write a novel? And that becomes an architectural question.

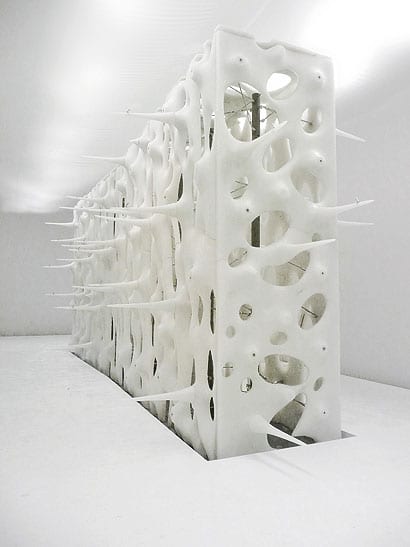

François Roche’s Things Which Necrose, a structure that decays in humid air, built for the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark, 2009 WE Yes, it does, I see that. If you drop Patrick McGrath on a tropical island, he will never write anything again. I feel the same way. [I couldn’t write in] somewhere that isn’t obviously a social machine and a struggle. I’m fine with villages; tiny British villages with three public buildings: a Post Office, a general store and a pub. My girlfriend lived in one for years. GM François, your buildings are open to time. You’ve got the building that’s fuelled by a cow – the cow walks out, takes a shit, and fuels the building. You’ve got the spider web house with the nets that are going to change over time because there are plants growing through them. And there’s the building in Thailand that accumulates the dust of the city. By including time in your buildings are you including narrative and entering the realm of the writer? FR We don’t consider a building as the end of the story, it’s a fragment of the story. So we need to construct the story for before and after the construction of the building. Architects work a lot with mathematics, and it’s very difficult. In fiction, you have “if”, “why”, “maybe”. When you are writing mathematics it’s hard to protocolise “maybe”. It’s a big problem in architecture schools now. We are inside this movement of mathematics, using mathematics as a determinist system, and [we must] include something that is un-determinist or unpredictable. In the script – we talk about scripting, we talk about following the scripts – it’s very weak compared to your script. And if we want to force the complexity of our script we need a lot of knowledge. WE It sounds like you’re actually interrogating your own materials, which I find very interesting. FR Yeah, it’s not only to interrogate but to interrupt the integrity of something. I love to push people to be confused, to be in front of something they are not able to consume easily. WE They have to work that little bit harder to understand what’s in front of them. FR Yes, exactly. Like in science-fiction, you need to identify a format of something, the format is always different. WE That is absolutely science-fictional thinking, it’s “the door dilated”, it’s that thing in front of you that didn’t exist before that you just have to work that bit harder to comprehend, which is why so many people claim they don’t like science-fiction. They feel like they’re being tricked by the text. FR Exactly. Many people refuse to be absorbed by something they don’t know. Žižek talks about Kinder eggs. Kinder eggs were forbidden in California in the mid-1960s because it was a total disruption of American life where everything needed to be predictable, and here you didn’t know what was inside. You could buy cocaine but not Kinder eggs because they thought it could corrupt the young. Kinder eggs were made by the Germans after the war to reconnect to the unknown and to force the kids away from the lazy period where everything was free. It’s a beautiful articulation of knowledge. GM One thing that kept coming up with you, Warren, was moving into new buildings. I feel like many people have killed themselves here. And that’s got this kind of almost hauntological forcefield … for some of you who look for narrative and possibilities you can build that sort of history into a building, almost like a presence.

François Roche’s Things Which Necrose, a structure that decays in humid air, built for the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark, 2009 WE I was told a story many years ago about a couple who locked themselves in a room for three weeks and did nothing but take LSD, have sex, cut themselves and smear all their bodily fluids over every surface of the room. This is obviously an extreme example. You could feel it. FR You know the Winchester house? It is very interesting … constructed over 40 years [by the widow of the man who created the Winchester rifle]. Every time she closed a wall, she closed a window, to put in jail the ghost of the people killed by the rifle. Her husband died and she gained the royalties from the rifle – she became afraid of the money that was coming in, and to stop the guilt over the deaths of the people killed by the rifle she tried to trap the ghosts in the house … it came to be 150 rooms. GM I think François has a unique body of work which would be interesting to someone like you, Warren, because it’s about growing architecture – this kind of new discourse which is taking over schools, becoming much more speculative and imaginative. You can build anything nowadays. WE As a science fiction writer I’ve got to sit here and think wouldn’t it be great to design a building that exuded pharmaceuticals … Are we GM A famous example in the US of bad design was the FEMA trailers after the hurricane Katrina. After people lived in the trailers long enough, formaldehyde leached by the plywood was causing respiratory illnesses, asthma and probably cancer in the future. So why not build plywood that’s injected with something good? Why not an anti-malarial in the plywood? I’m quite curious to see what the architects and the science fiction writer can learn from each other. FR I asked Bruce Sterling two years ago to write about the building we’re finishing, and he wrote about the building but he took the position of 30 years after it was completed and it helped us a lot to finish the building. He put the critic in the future, which is very interesting, and because of that he helped me to negotiate the present better. GM What kinds of things was he imagining? FR We were doing the building in the forest entirely with spider nets and wood, a lot of textile and fabric to start to push away the forest and use the forest as wall. It was 500sq m, so not too big, but there is a kind of porosity where you don’t know whether you’re inside a building, inside a forest or inside a labyrinth. He wrote a text about some guy coming to research this house in 30 years with a GPS, and he was not able to find this house – it had disappeared entirely. Like the Blair Witch house or something. Because of the text we took care to blur the boundaries of the house we were in construction, we blurred the boundaries. So it’s interesting how the text as a report from the future is at the same time modifying what you are doing in the real time. Honestly that is fantastic. GM Would you ever design a building knowing that it might inspire somebody like Bruce Sterling to write a story like that? FR No … I hate when in architecture books there is only comment on the building. All the time I ask somebody to make a layer, to invent another story and to pull layers and to push reality to go in some, not to unfold the reality but to push the reality a bit further or beyond the construction.

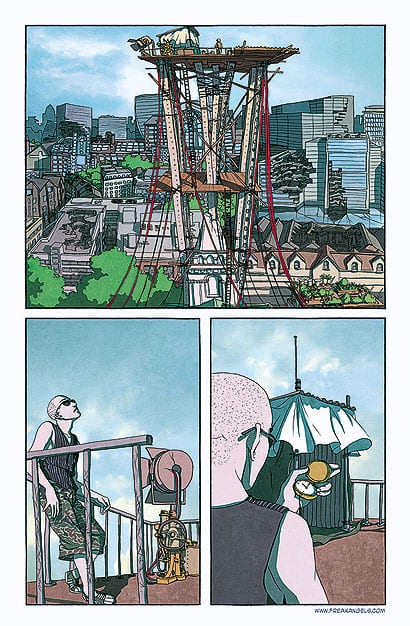

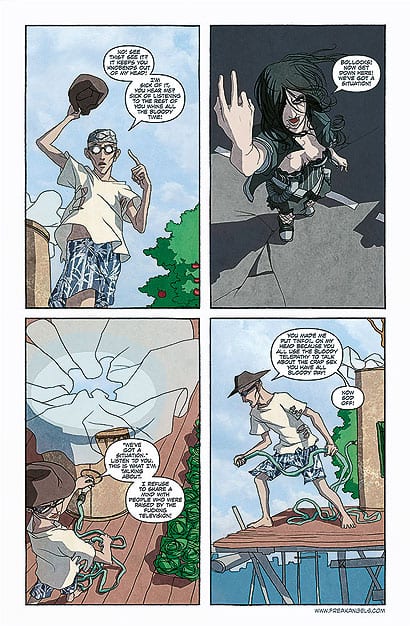

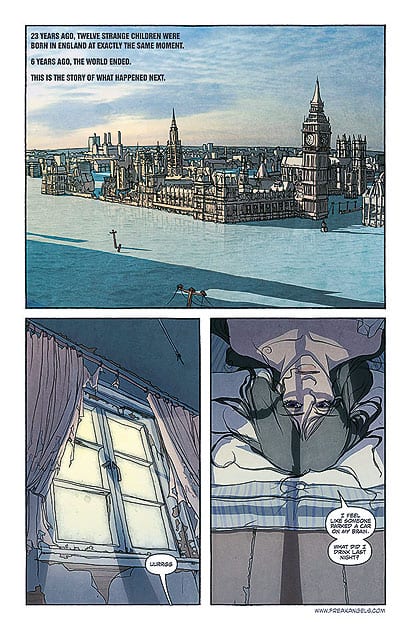

Illustrations by Paul Duffield for Warren Ellis’ serial FreakAngels (image: www.freakangels.com) WE People have an idea in their heads of what science fiction is and they don’t imagine it as engaged with the world. The function of science fiction is in fact to be directly engaged with the world, to affect it and to allow yourself to be affected by it, to learn from it and to take on whatever it says about the social condition. GM If you could influence a building the way that Bruce influenced François’ building, which direction would you be interested in? WE In many science fiction stories there is the house that follows you, the house that reacts to you, that’s been a classic setting for many years. It could be a house that will fuse with nature, or houses would exude pharmaceuticals or homeopathic remedies in water vapour, perhaps the roof is a fog farm and that’s where your water is coming from, which in certain parts of the world is going to be more useful than solar panels in the future. Where I am now in Essex it was classified as semi-arid by the United Nations ten years ago. This is the same part of Essex of course that’s going to get washed away when water levels rise. The architectural possibilities of that are interesting to me, many of the buildings in my area have been built on flood plains. I would be interested in a house that’s going to rise with the waves. GM Some people would call that dystopian … WE I wouldn’t define that as dystopian, it’s embracing change. There’s something unnerving about it but all these things have another side, it’s not binary, there are many useful things … Obviously that’s the slippery slope because that’s how things are sold to us, the ID card will be a useful thing but we all know what it’s really for, but I choose not to discount the possibility that some things might work out. FR I try to negotiate with my romanticism – I know it’s a bad word now, romanticism – the project we are doing about all this kind of charming distress we are talking about. When you are a romantic you try to be affected by a situation. You are like writers, you need to be outside but at the same time inside. When we start a project, we switch off the possibility of receiving a lot of influence, even contradictory, to feel the situation. And when you arrive in your location, you have a panoptic view, you embrace everything but in a way you need, to focus on what could be the input and output to reveal the condition of a situation and to extract from this condition something as a project. WE When I say “I would like my house to have wave motion generators to produce power for me and if some of that power could be hived off to desalinate sea water”, I’m not necessarily being a pessimist or a cynic I’m just covering my options and embracing the environment. Just because I carry a Swiss army knife instead of a penknife doesn’t mean, you know, I think I’m a dystopian or pessimist, it’s just I might actually need a screwdriver. GM I was once describing the future impact of swine flu on the city on BLDGBLOG and somebody on another blog accused me of romanticising disaster and beautifying negativity. But let’s do the opposite and describe a non-swine flu future where everybody lives happily and gets married and has a house etc, now you are accused of being, what, bourgeois? No matter what it is you are describing your enthusiasm for, you are either romanticising the apocalypse or you want everyone to live in the suburbs and be safe forever. WE We are primarily talking about our perspective from Western culture and Western problems and there are still places where those are good problems to have. We’re imagining a swine flu apocalypse for whatever reason, and right now there are fighters in the Congo, guerrilla fighters, who are practicing cannibalism during an ebola outbreak. That is bad problem to have. I think there’s perspective to be had in just the layers of discussion. There are apocalypses happening that we can’t conceive of, still.

Illustrations by Paul Duffield for Warren Ellis’ serial FreakAngels (image: www.freakangels.com) GM One thing that’s exciting about both of your work is the idea that architecture lends itself very well to storytelling and storytelling lends itself very well to being translated into buildings. And for me the reason to talk about architecture and science fiction is to acknowledge long-term effects, narrative, events, the way a building will be transformed over time … can you design a building that will inspire people in a certain way or could you write in a certain way to have architectural effects later? FR It’s very beautiful when you share a movie, when you tell someone “I saw a movie about an incredible story” and you transfer the curiosity to go see the movie. When you talk about a building you say “I saw a glass cube beautifully done” it interests nobody, just the architecture field. If you say “I see a glass cube which is melting when it is raining” or “a cow appears to warm the building and it smells of cow”, you say “oh, I want to go there”, it’s touching something psychologically in me. The problem with now is the building cannot be told, it’s just dry icon, and dry icon is a catastrophe, nobody will want to tell a story of a dry icon. There is a specific high-chemistry relationship which forces you to understand something different like a movie, to understand, to open your mind on something, not to be only a slave of coquetry and elegance. Last are Norman Foster … they are ridiculous, they are just the dick, the emission of the dick of the mayor, and that is problematic. So you could say, OK, the dick of the mayor is one hundred metres high … the story could be interesting because of the spermatic jets on the top, no, but you understand it’s ridiculous now. No, I want to be provocative as well. WE Just get that in at the end, yeah. This conversation took place after Thrilling Wonder Stories, a symposium at the Architectural Association curated by Liam Young of Tomorrow’s Thoughts Today and Geoff Manaugh of BLDGBLOG www.tomorrowsthoughtstoday.com

Illustrations by Paul Duffield for Warren Ellis’ serial FreakAngels (image: www.freakangels.com) |

|

|

|

||

|

Left to right François Roche, Geoff Manaugh and Warren Ellis (image: Maja Flink) |

||