The green belt has always been an unhappy mash-up – a patchwork of leftover land, neither urban nor rural. But the idea of limiting the city is essential, both for energising the space within and freeing the natural world beyond

The view west from Tilbury Fort, Essex, 2019. Image: Chris Dorley-Brown.

The view west from Tilbury Fort, Essex, 2019. Image: Chris Dorley-Brown.

Words by Phineas Harper

Fiercely defended by some, while under siege from others, green belts are – depending on who you talk to – national treasures, arcane throwbacks, the cause of the housing crisis, saviours of the countryside, too permissive, too constraining, sacrosanct or idiotic. For nearly 200 years, they have been prey to cultures intolerant of limitation. Consequently, they are closed, unloved landscapes, bereft of biodiversity and constraining in a sense that is far more insidious than their creators imagined.

Our resistance to limits is a foundational myth of neoliberal culture. ‘There are no limits to growth and human progress when men and women are free to follow their dreams,’ declared Ronald Reagan in his re-election inaugural address in 1985. He was, of course, lying. Only a decade earlier, the Club of Rome had prophetically warned that, if the physical limits to growth are ignored, society will ‘overshoot those limits, and collapse’. But life without limits was a powerful propaganda message for Reagan’s doctrine of deregulation. Today, overcoming limits is still celebrated through cringeworthy clichés: ‘Know no limits’, ‘you are your only limit’, or ‘don’t tell me the sky is the limit when there are footprints on the moon’. Even as unprecedented fires, floods and biodiversity loss scream of planetary boundaries pushed to breaking point, our relationship with limits remains antagonistic. This antagonism is played out in the quasi-rural landscapes of green belts, land designations which have shaped the relationship between the city and the rural for generations.

Green belts, however, are not particularly green. Instead they are a patchwork of gated industrial farms, landed estates, private golf courses (golf takes up 2,500ha of green belt within London alone) and even airports. In the UK, only 3.9 per cent of green belt land is openly accessible. These paralysed girdles surrounding our cities embody the paradox of a culture both addicted to, and sick from, growth. They are an unhappy mash-up, neither commanding the clarity of an affirmative threshold to the rural, nor the generosity to be used well by those who dwell within them. Instead, could we embrace the positive possibilities of reimagined urban limits, choosing them not under duress, but in the knowledge that hearty moderation is better than sickening over-indulgence? As climate change and inequality intensify the struggle over land, green belts are becoming a critical site for political and architectural imagination. But to understand what green belts could be, we must understand what they were intended to be.

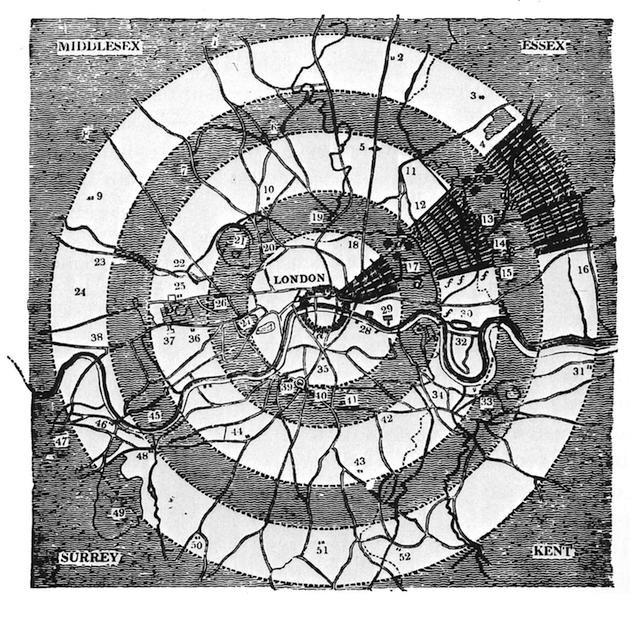

Loudon’s breathing zones were formed of concentric circles of alternating parkland and city.

Loudon’s breathing zones were formed of concentric circles of alternating parkland and city.

In 1829, the year before marrying author of proto-feminist science fiction novels Jane Webb, the garden designer John Claudius Loudon proposed vast concentric rings of alternating parkland and city radiating out into London’s hinterland from Blackfriars Bridge. The circular ‘breathing zones’ were never realised, but like Webb’s sci-fi predictions that women would soon wear trousers and humanity would be connected through information networks, the visionary botanist had planted a seed. The great urban parks of the 19th century bear his influence, providing respite of artificial rurality in city centres. Then, a decade after Loudon first unveiled his ideas, they were trialled for real – in Australia. In the 1830s, British colonists declared into existence South Australia and established its capital in the Kaurna land of Tarndanyangga.

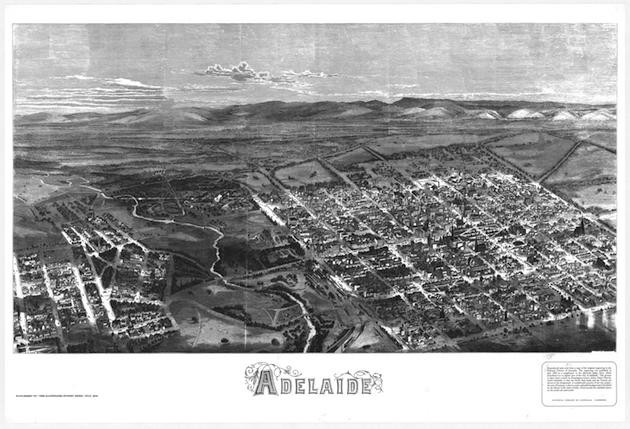

The new capital city of Adelaide, designed by colonel William Light, was split into halves either side of the Karrawirra Parri River and surrounded by a ring of parkland forming a figure-of-eight green belt. The idea caught on and green belts were soon created in New Zealand, the US and elsewhere. As populations grew and cities oozed outwards, these belts became seen as a tool to constrain urban sprawl. A century after Loudon published his eccentric designs, the Greater London Regional Planning Committee took up a version of them, recommending a Metropolitan Green Belt ‘to provide a reserve supply of public open spaces’. Today a remarkable 13 per cent of England is designated as green belt land by statute, entrenching strict conditions on its use and development.

Shibam in Yemen – the city’s fortified perimeter has given rise to an urban landscape of tall mud-brick towers. Image: Alamy.

Shibam in Yemen – the city’s fortified perimeter has given rise to an urban landscape of tall mud-brick towers. Image: Alamy.

Yet many of the most stimulating urban thresholds are much more abrupt. Shibam in Yemen, for example, is a city comprising mud brick towers rising between five and 11 storeys. The buildings are so tall because Shibam’s fortified perimeter wall is a hard edge, meaning its citizens build up, not out. Venetian architects, constrained to building on the lagoon’s 118 small islands, have poured architectural intensity into what space they had, creating one of the richest urban realms in the world. In America, infamous for sprawl, would Manhattan have achieved such architectural dynamism if it were not hemmed in by the Hudson river? Perhaps the non-negotiable thresholds of New York, Venice and Shibam imbue their cities with an architectural energy that green belts lack. As we edge towards the centenary of the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947, which established them in the UK, what does the future of green belts look like?

Many call for managed deregulation, including right-wing think tanks such as Policy Exchange, consultancies like QUOD and property developers like U+I. Some investors, scenting an opportunity, are lobbying journalists and politicians. In 2014, the Economist claimed that ‘the supply of land in Britain is artificially restricted’, and called for the deregulation of the green belt to ‘free up more land’. Just two months later, the Guardian published a list of reasons to build on green belts, asserting that they drove property prices out of reach. The argument goes that British property is expensive because there are not enough homes for the population; a straightforward mismatch between supply and demand.

Illustrated view of Adelaide, showing the figure-of-eight parkland designed by William Light, 1876. Image: Alamy.

Illustrated view of Adelaide, showing the figure-of-eight parkland designed by William Light, 1876. Image: Alamy.

This analysis is overly simplistic to the point of cynicism. In reality the scarcity of homes that we call ‘the housing crisis’ is not the cause of high house prices but a symptom. Developers know that when house prices are high, they can maximise their profits not by building lots, but by eking out fewer homes slowly. Far from suffering an undersupply of land, housebuilders in fact sit on it, completing around 42 per cent fewer homes each year than they have planning permission for. Without wider systemic reforms, all that deregulating the green belt would generate is huge windfalls for land owners.

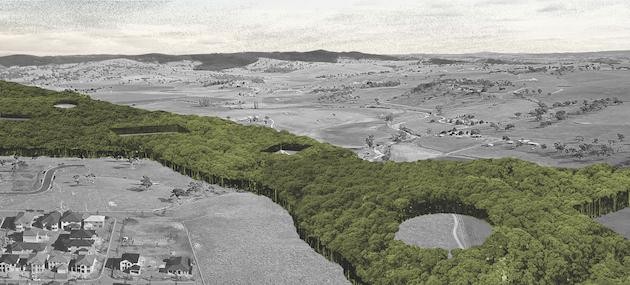

A more promising idea is emerging where green belts began. The Cumberland Plan adopted by Australia’s Government of New South Wales in 1951 proposed a vast green belt encircling Sydney. The belt was never properly implemented and Sydney now extends far beyond the city limit intended by Cumberland County Council, threatening to consume the entire basin. The sprawl is spurring young Australian architects to propose new ways of establishing a positive edge between city and country. Sydney-based studio Other Architecture envisions a so-called Burial Belt, a thickly wooded cemetery that would wrap around the city. Over 1.5 million people will die in Sydney before the middle of this century, but no cemeteries have been built since 1960. Even in a nation as vast as Australia, citizens’ wishes for their final journeys may soon go unfulfilled. Instead, the Burial Belt would marry urban- scale reforesting with interment plots, establishing a remembrance woodland. Where the Cumberland green belt failed to capture the hearts of Sydneyans, Other Architects hopes its Burial Belt could form a stronger border, imbuing the band of trees with meaning, leveraging respect for the dead to curtail sprawl. Its design mixes the profane with the profound to create a spiritually nourishing alternative to failed green belts of the past.

Today, Adelaide in South Australia still incorporates the principles of green space adopted in the 19th century. Image: Andrey Moisseyiev

Today, Adelaide in South Australia still incorporates the principles of green space adopted in the 19th century. Image: Andrey Moisseyiev

Peter Barber Architects in London is also exploring the possibility of a more articulated city limit. The practice’s 100 Mile City proposal envisions a ribbon of dense housing peppered with small schools, squares and factories running the circumference of London. Barber estimates that a ring just 200m wide and four storeys high would provide accommodation for 3 million. To one side, suburbia, now revitalised and sprawling not out, but in towards the core of London. To the other, a sharp switch to fields, forests and wetlands. Like approaching a medieval walled city, London would have a physical, not just administrative border. For Barber, the project is a provocation. ‘It’s a kind of preposterous idea,’ he says, ‘but it’s much less crazy that the situation we find ourselves in.’ The project is rooted in an ambition to give the edge of the city a civic generosity.

Royal College of Art graduate Joe Mercer is also exploring ways to reconnect the green belt with its lost public ambitions. Over half of London’s green belt land is used for agriculture, much of it inefficient meat farming. In his Cornucopia proposal, Mercer envisages a ring of transport infrastructure connected to Dutch-style greenhouses for land-efficient growing. By concentrating agriculture more tightly, he argues, it is possible to reduce the green belt land used in farming from 59 per cent to just 7 per cent, quintupling publicly accessible space instead. For Mercer, this would ‘allow the landscape to return to a feral state and fulfil the original intention of the Metropolitan Green Belt as a collective natural asset’.

Burial Belt, Other Architects’ proposal for using woodland burial to combat urban sprawl in Sydney. Image: Other Architects.

Burial Belt, Other Architects’ proposal for using woodland burial to combat urban sprawl in Sydney. Image: Other Architects.

Today the green belt survives as an unhappy botch between neoliberal antipathy to limits and a reactive rural planning culture that finds it easier to deny than propose new solutions. We are left with cities that bleed into rurality with land not quite on the table for investors to speculate on, but not quite off either – a schizophrenic hinterland. How can we escape this? Ecological economist Giorgos Kallis believes the answer lies in challenging the drive to surpass our limits. ‘Like women and men who mature in life when, coming to terms with their own limits, they find their true desires,’ he writes, ‘civilisation will have truly progressed when collectively we come to know and respect our limits.’

For our green belts to serve us better, we must first serve them better, by not just grudgingly accepting them, but through a process of better defining and celebrating the border between rural and urban – of finding and enjoying our limits.