|

|

||

|

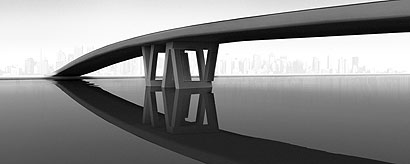

Like many product designers, Dror Benshetrit doesn’t like being called a product designer. Nor does he see himself as a mere form-giver. He’s created everything from the roundly pleated Peacock Chair for Cappellini, to a boutique interior for fashion designer Yigal Azrouël and a development plan for an island off the coast of Abu Dhabi. And in light of his latest project – a new structural truss system called QuaDror – he’d prefer to assume the title of “transformer”. Benshetrit’s QuaDror – so named to reflect its central, four-part form and, well, its creator – is swiftly rebranding the Eindhoven-trained, Israeli-born New Yorker as a polymath of architectural designs both large and small. The result of more than five years’ development, QuaDror was unveiled at Design Indaba in Cape Town this February. Comprised of four identical, interlocking L-shaped parts joined in oppositional orientation from one another, QuaDror promises to revolutionise the structural efficiency and integrity for projects of varying scale, from micro- to megastructure. The geometric parity of the truss allows for economical flat-packing and construction, and modular units can be aggregated and stretched to a number of configurations and sizes. Elongate the legs, and the unit opens up to a rhombic sawhorse that’s 25 percent stronger than the traditional A-frame. Its applications are just as versatile as the A-frame’s: the diagonally intersecting trestles are conceivable not only as table legs, but also as bridge supports and wireframes for buildings as large as skyscrapers. Stacked and linked like a honeycomb, the solid, flat-standing units can create beautifully tessellated, super stable room and street dividers that insulate sound significantly better than a standard, smooth-surfaced wall. “There are a few things that we keep discovering all the time,” Benshetrit explains. “There are also a few things we aren’t speaking about yet, some additional categories that we are still developing.” As he speaks, he casually opens and collapses a number of QuaDror demo models scattered about his desk: one made of wood, another of steel, and a third in Corian. “We’re spinning models, we’re sketching in our books, and sometimes we’d be showing something and clients would ask us, ‘Well, what is it? Is this a box or a building? Is it this big or THIS big?’ And sometimes, it’s exactly the same. It uses the same principles, it carries the same certain geometrical logic.”

As the project grows increasingly beyond his specialised training as a product designer, and into engineering, architecture and urban infrastructure, Benshetrit is quick to admit he’s hardly an expert of all trades. “We’re not intending to be knowledgeable about all of the applications – it’s all about collaborating and teaming up with the right people.” Since the unveiling at Indaba, Benshetrit says the influx of queries from potential collaborators has been huge. “We are talking with a lot of people.” Though he hesitates to name anyone in particular, for fear of showing his cards too early in the game, Benshetrit says StudioDror has been speaking with several architecture firms, engineers and even medical firms, that are exploring the use of the form at more of a micro scale than he had ever thought possible. “When we met with people in the beginning we showed them everything we could do with QuaDror. It was a little overwhelming, almost like, ‘What are you trying to do, save the world?'” he says. “And it’s like, well, yeah!” he adds, only half-jokingly. Beyond the individual scale, Benshetrit has far-reaching goals for his self-named geometrical truss. At Indaba, his talk focused on implementing QuaDror for relief housing in favelas and slums in developing countries. “When we think of slums and favelas and the poor structural conditions they operate in, you’re talking about billions of people who live in those conditions,” he explained. “So when you talk about scale, it’s not just about a scale of size, like a hundred-storey building, but a scale of influence.” Back at his studio he continues to toy with the models (prototype miniatures, really, of future highway dividers, high-rises and bridge supports) either idly, as if they were Rubik’s Cubes, or meditatively, as if they were a pair of Chinese exercise balls. It’s not hard to read the gestures of Benshetrit, who is tall, well built and comfortably reclining in his office chair, as those of a generational visionary (or megalomaniac) reimagining the world with his sculptor’s hands. As QuaDror starts to be implemented in the coming months, the strength and ingenuity of its design, which is protected by no fewer than 16 developing patent provisions, will be put to the real test, as a host of engineers, architects and designers eagerly look on. “We’ve trained so many different players to go to the Olympics,” Benshetrit says. “Now they’re all lining up and waiting for the race to start.”

|

Image Clayton Cubitt

Words Aileen Kwun |

|

|

||