|

|

||

|

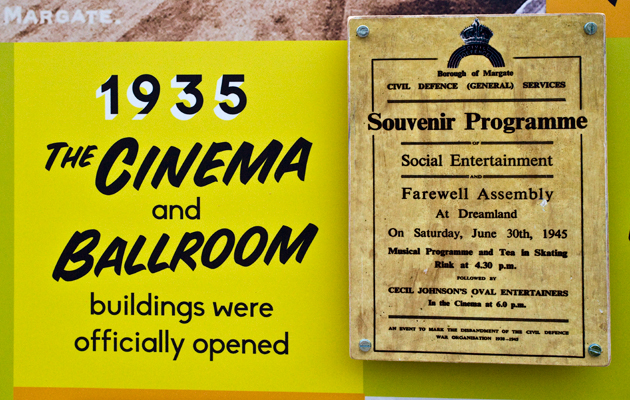

In line with the seaside town’s revival, Margate’s traditional fairground has reopened to the public – but with east London creatives, rather than children, as its main target audience. Its designer, Wayne Hemingway, explains why the attraction’s longevity depends on more than just nostalgia Twenty, even ten years ago, you’d associate Margate most with coastal siblings like Bognor Regis, or that matriarch of British seaside resort towns, Blackpool. The most even-handed assessment would be to describe these destinations as revelling in a certain tackiness, a good-natured pastiche of the era that pre-dated the package holiday but whose brave face was now starting to slip. But it would only have been possible to talk about Margate in those terms ten years ago if you hadn’t actually visited. By then the mask had truly fallen, the town beset by unemployment and low investment, with its main lure, the Dreamland theme park finally mothballed in 2003. This traditional fairground, opened in 1920, was the epicentre of the community; when its feature attraction, a historic wooden rollercoaster (the oldest in Britain), was partially destroyed by an arson attack in 2008, there was a sense of grief.

The start of Margate’s renaissance was signalled in 2011 with the opening of the David Chipperfield-designed Turner Contemporary. Even before this, there had been a notable bloom of independent shops, artists’ studios and boutique hotels. This was a different scene to that which the pre-existing community were accustomed to attracting and now the town had unexpectedly begun to feel closer to a different type of British seaside retreat: to the Whitstables, Aldboroughs and Southwolds, with their arts and music festivals. Then came the news that Dreamland, bought by the council in 2005 to save it from the developers, was to be restored. But how would the park respond to its changing surroundings? The task of guiding that transformation was left to designer Wayne Hemingway, formerly of fashion label Red or Dead and now head of Hemingway Design, a multidisciplinary practice that covers everything from marketing to housing schemes. For Hemingway the process centred on identifying the park’s potential audience, a group he unashamedly describes as “hipster”. A large quotient of the park’s visitors had always been drawn from the East End of London, and it’s hoped that the same will be true of this new incarnation. But, just as the demographics of the eastern quarter of the capital have shifted over the past 20 years, so too has the projected ethos of Dreamland. These young, urbane adults – creative and tech sector workers mostly – like to think themselves a culturally astute bunch, not the sort given to travel an hour by train simply on the promise of a Mr Whippy and a ride on the helter-skelter. |

Words Peter Maxwell |

|

|

||

|

The arcade eschews beat ‘em ups and penny-pushers for a stock of cult-classic pinball machines |

||

|

Thus, while the park celebrates a certain nostalgia and centres on rides, the attitude is one of playful irony, kitsch, but with high production values; as the title of two attractions, the Born Slippy and the Counter Culture Caterpillar, attest, there are in-jokes here that play to a very specific crowd, while the site manager’s pet favourite – the Hurricane Jets – is marketed as being perfect for aspiring Dan Dares, a reference likely to be lost on most children. Everything here is reassuringly authentic, sourced from parks around the world, with the dressing – food stands, seating, bins – upcycled by a team lead by Hemingway’s son. The newest thing, paradoxically, is the all-important rollercoaster, built as an exact replica of its fire-damaged predecessor. The ensemble fits somewhere between rockabilly revival and an anglophile Wes Anderson (though the rest of Margate remains decidedly Ken Loach). Even the wayfinding seems to defer to a discerning audience, the sitemap more concerned with exemplifying a wistful, carefree aesthetic than providing navigational assistance to lost toddlers. The overall colour scheme is telling, too: managing to be bright without shading into gaudy, and despite the confluence of hues, light and movement, the whole thing harmonises in a way that might be lost on a crowd interested simply in spectacle – evidence perhaps of Hemingway’s decades of experience orchestrating shows at London Fashion Week. But it’s the food provision that tells the story best, offering “a fresh fish counter with local day boat caught fish”, authentic Thai, champagne and craft beer alongside the usual mix of (organic) burger counters and candyfloss wagons. Beyond the fair are a host of ancillary venues that add to the site’s offering for culture-loving visitors: the arcade eschews beat ‘em ups and penny-pushers for a stock of cult-classic pinball machines, while the ballroom and roller disco are set to be late-night gig venues for bands and DJs. This programmatic direction culminates in the second phases of the project, pencilled for next year: a huge outdoor concert arena, aiming to turn Margate’s waterfront into some sort of perennial festival-on-sea. We talked to Hemingway about the impetus behind this hipster hangout. |

||

|

A new rollercoaster (top) has replaced the original wooden version (above), which was partially destroyed by an arson attack in 2008 |

||

|

ICON: How did you get involved with the project? Wayne Hemingway: We’ve been working on Dreamland for four years. We’d already heard what was brewing down here in Margate – we’re very attuned to community uprisings, which is essentially what this story is. We were asked to bid for this project and thought we’d come down to Margate – we were simply bowled over by it. The area has that wonderful shabby British seaside feel. Then you walk to the old town and see the range of independent shops and artists’ studios appearing there. Even four years ago, you could see the possibilities. It was something we immediately wanted to be involved with. ICON: What was the initial brief and did it change at all? WH: We didn’t agree with the parameters of the initial framework so we challenged it. The request was to develop a heritage theme park and we didn’t think that would work long term. We granted that the heritage aspect would have to be part of the package, but thought the park would have to appeal more widely, otherwise it would be an attraction that really only bore one visit. To rely too heavily on the heritage aspect meant it would be fixed instead of fluid, that the audience would know what to expect. We wanted, through a broader, moving range of events and a twist in the design language of the park, to create something that would continuously surprise.

|

||

|

A roller disco is part of the park’s late night offering

An original ride at the park: the Haunted Snail |

||

|

ICON: It seems like it’s quite an adult-orientated venue, rather something target at kids or even young adults. Is that the intention? WH: It is. We did our research: what children want are fast rides – they want Alton Towers or Thorpe Park. Dreamland could never be that, we don’t have the money – the cost of a new ride at Alton Towers is more than the whole of this project. Instead, we want to appeal to people who have got young kids. That way it’s not so much relying on “pester power”. It’s actually the parents – who are the people who have the money, after all – saying, “yeah, this looks cool”. Though it’s many years away, the mooted London Paramount theme park will be on the same train line, but we’re not competing with that – we couldn’t if we wanted to, but it’s also not the right approach for Margate. This is a community project done with grant money. Some of the bodies that have funded Dreamland see their financial injection almost as an act of philanthropy rather than an investment, so it’s an entirely different ethos. It’s much the same as the way that east London was originally brought back to life on the cheap by people who moved their and placed some personal investment in the community, rather than the big developers – though, of course, they’re running the show there now. ICON: What’s the community engagement process been like? WH: The story is that the local community pleaded with the council to save the site, to prevent housing from being built on there. They organised and set up the Dreamland Trust, they went court and stood outside at the hearings, they petitioned. They established a Facebook group with 40,000 supporters. While the park was closed, they’d come with spades and shovels to tidy it up weeds. People would queue up just to pay three quid to get inside and get a piece of paper that confirmed they’d been there, because they knew that, if they got 10,000 people, they could raise the 30,000 needed to open a visitor centre. |

||

|

The fairground’s overall colour scheme manages to be bright without shading into gaudy |

||

|

ICON: Traditionally, you’d associate Margate with resorts like Blackpool, but these days the ethos of the town seems to be moving closer to that of Aldeburgh or Whitstable – places based around the arts. How does Dreamland fit into that shift in emphasis? WH: I think the reason for that is partly its proximity to London, and in particular the east of London, which is the capital’s creative hub. Margate is one of the most accessible sandy beaches from Shoreditch – that’s one of the things we instantly recognised. Then we saw the Turner Contemporary for the first time and the impact it was having and it all seemed to fit. ICON: Do you think that there are two communities in Margate now: the pre-existing and the interlopers? WH: When a place is changing, there will always be that shift, but I think in Margate it is genuinely being welcomed, which is not always the case. I don’t sense any reticence. There’s no getting away from the fact that certain aspects of Margate are gritty, but that can be hugely exciting. We’re creating a lot jobs here. This is a genuine chance to change people’s lives. |

||

|

|

||