All photos from the archive of Denise Scott Brown

All photos from the archive of Denise Scott Brown

As a new exhibition of Denise Scott Brown’s photographic efforts opens in London, Icon considers why the 86 year-old is still one of the most important voices in architecture today. By Rita Lobo

At the height of the ninth decade, Denise Scott Brown remains one of the most influential architects in the world. She is a partner at Philadelphia firm Venturi Scott Brown and Associates, which she built up with Robert Venturi; she co-authored the seminal treatise Learning from Las Vegas, the book that birthed post-modernism; she’s been a lifelong advocate for collaborative, inclusive and diverse architecture – since long before these were buzzwords. She describes herself as the Grandmother of Architecture, and she’s one of the only voices arguing for a more inclusive, popular, and functional industry.

As an architect, her star keeps on rising, even though she bowed out of design long ago to focus largely on writing and research. Earlier this year, the Sainsbury Wing at the National Gallery in London was awarded Grade I listed status by English Heritage; reserved for buildings of exceptional interest like the Royal Albert Hall, and the Houses of Parliament. Only 2.5% of protected buildings in the UK are Grade I listed and the Sainsbury Wing is the only post-modern effort to make the cut. ‘People have a wrong view of what postmodernism is, at least for us, and how we came at it,’ Scott Brown says of the building, which she designed along with husband Venturi to house the National Gallery’s Renaissance collection. ‘Now what’s happening is people begin to understand we have nothing to do with something that I call po-mo, which is an illegitimate inference, I would say.’

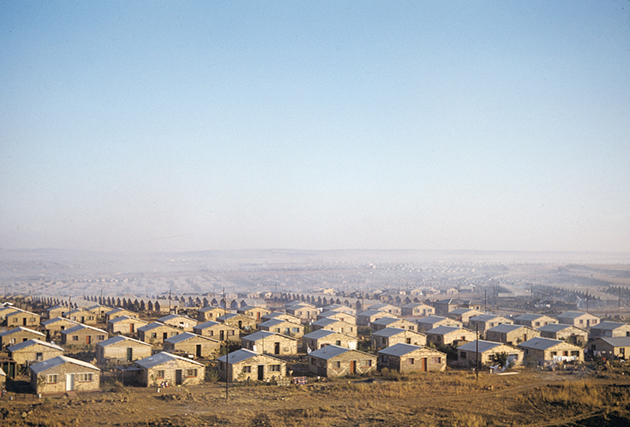

Los Angeles, 1968

Los Angeles, 1968

For Scott Brown, post-modernism is rooted in the post-WWII social thought. ‘Isn’t it lovely for everything to reach the sun and be made of glass, and to be rolling fields,’ says Scott Brown about her colleagues’ reluctance to embrace the social implications of post-modernism. ‘Then, the reality doesn’t translate that way on social levels, on physical levels, and architects won’t do the learning to learn how to do better. We just have a chance to do the good we can do. Acquire more lands, and the social vision would be that the working class would be living in these things. Of course, the exact opposite happened. People were terribly thrilled about Jane Jacobs. They’ve learned absolutely nothing from her, and they still do the same things they were doing 70 years ago.’

Scott Brown started her life in South Africa, before moving to London to study at the AA, before emigrating to the USA for more opportunity. ‘When I got to America, everything was very quiet. It was the 1950s. Within two years, there was a revolution going on,’ she says. She’s referring, of course, to the urban renewal movement that came to inform so much of her future work and research. ‘That was very, very exciting, and we’ve lived on that, looking at things architects want to confront about economics, society, and same way about natural systems, and trying to put it all together. It’s not the sociologist, but the creative architect with a social bend.’

Her ideas came to a head in 1968, by which point she had been working as an architect and teaching at the prestigious school at Yale, when she and fellow professor Robert Venturi took a trip to Las Vegas. Their ensuing book, Learning from Las Vegas, compiled from the research the pair carried out with graduate students on the taxonomy of the forms, signs, and symbols of the city, remains one of the most insightful critiques of Modern architecture.

Car view of strip by Denise Scott Brown

Car view of strip by Denise Scott Brown

Throughout her career, Scott Brown has been an avid photographer. The self-portrait on her standing, arms akimbo with her back to the Vegas strip at sunset, is her best-known shot, but certainly not the only remarkable image in the photographic oeuvre. ‘At the end of every studio I taught, I’d go out and take more photographs to teach the next studio,’ she says. ‘Those studios were not those architecture ones where each person has a problem. They were teamwork, and it was a group problem in which people shared different aspects. It was a very interesting way to teach.’

Wayward Eye, a retrospective of her pictures curated by her featured in London over the summer, based on a more extensive show curated by Scott Brown herself debuted in Venice two years ago. Like all of her research and architectural practice, Scott Brown’s images are thoughtful and emblematic. They are hardly just snaps of a full life but are imbued with her constant militancy and relentless thirst for knowledge.

It’s refreshing to see Scott Brown’s work rediscovered and celebrated. Though she has seldom stopped working and writing over her long career, lots of it has been overshadowed by her more well-known husband – Venturi was famously awarded the Pritzker Prize in 1991 for work they had completed together. There has been more than one petition to rectify this mistake and award Scott Brown her own gong, but so far Pritzker has been reluctant. But Scott Brown used the Prize (or lack thereof) as an opportunity to raise issues of sexism in the industry, but also to further the idea that architecture is a collaborative effort, and as such, it’s inherently inappropriate to single out only voices for awards, a position she voices to this day.

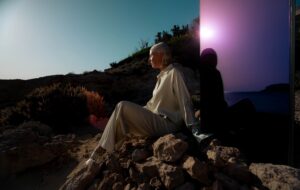

Denise Scott Brown’s view of New York City in 1962

Denise Scott Brown’s view of New York City in 1962

Scott Brown is delighted for the noise and has been using the petition and attention to speak up about what she perceives as injustices in the industry. ‘Then there’s the issue of the opportunities of young architects in firms, and that huge statistic that says 50% of students of architecture are women and have been for years now, and that they go into the office that way, and quite soon it reduces to 17% in the office,’ she says. ‘But also, there’s no place for old architects in architects offices, men and women. There’s this petition about me for the Pritzker Prize if you read the statements of the young architects there, men and women, they’re horrifying what they’re putting up with. So we have a long way to go in retrospect.’

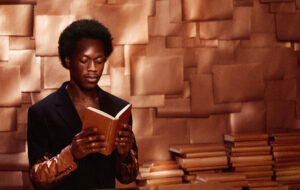

Denise Scott Brown started photographing architecture in Africa in the 1950s

Denise Scott Brown started photographing architecture in Africa in the 1950s

Scott Brown is right to question the role of the old guard continues to dominate architecture and is happy to use her position to voice her concerns about the state of the industry and to keep arguing for a more popular, and populist industry. ‘One young man came to me, and he had this big, wide smile because I said I’m architecture’s grandmother, no one else wants that title. I’m happy to have it. I’m talking up architecture,’ says Scott Brown. ‘So, with this big smile, he says, “You’re architecture’s grandmother, and you tuck architecture up in bed. But you know what’s happened? Architecture jumped out of the window and went out all night.” So I said, “Just keep away from cities because you’ll be a menace. Just don’t try to design cities, because you’ll do so much harm. By the way, when you climb back in the window land on your bed, I hope it’s your grandmother waiting for you, not your mother because your grandmother will be a lot more kind”.

Denise Scott Brown: Wayward Eye is at the Betts Project in London from July 11 to 28

The exhibition is initiated and co-created by PLANE—SITE, Betts Project and Jeremy Eric Tenenbaum