|

Claude Parent’s radical architectural theories – rejecting “bourgeois” verticality for ramped cities and sloped buildings – chimed with the spirit of 1960s Paris Working together with Paul Virilio under the banner of “Architecture Principe” in the 1960s, Claude Parent developed a theory (it had to be a theory – this was, after all, France) that we were living in the age of the oblique. This is how it went. The pre-industrial era was the age of the horizontal. The fields, the landscape, travelling on foot along paths, it was flat. The industrial revolution changed all that. Factory chimneys and steel-framed skyscrapers announced the coming of the age of the vertical. It culminated in the launch of rockets into space, the ultimate escape from Earth’s gravity. The 1960s was a time of crisis (France is always in a time of crisis, but this was a special crisis). This was to be the age of the oblique, the slope, the ramp, an architecture of resistance and non-conformity to gravity or the bourgeois values of furniture on floors. Chairs? Who needs them. We can just lounge on the sloping surfaces. Stairs would become redundant, cities could be built at angles, expressing dynamism through a radical architecture that shook off the dated hierarchies of post and beam.

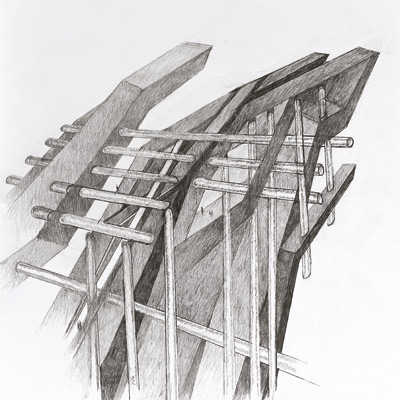

Parent, now 91, in his Paris studio Sitting in his Paris studio a few weeks ago, Parent, now 91, described the idea to me using a book. He placed it at a 45-degree angle to the surface of the table and explained how this was an architecture of openness. On one side a slope that could be climbed, on the other a roof which could be entered under. “Doors,” he told me, “are holes cut into the barrier of the wall. It is absurd.” It is, in its own way, irresistible, this architecture of resistance. And Parent’s beautiful pencil drawings of extraordinary ramped cities, of sci-fi settlements like spaceships, remain seductively mad utopias. In their ambition they not only presage Daniel Libeskind and Zaha Hadid, they arguably surpass them. While those one-time deconstructivists pandered to the bourgeois values of the level floor (their deceptively dramatic facades revealing themselves as a sham), Parent went all the way. His interiors were landscapes, strange visions of a theatrical, disorientating world to fit a radical new society. He was subsequently, naturally, almost completely ignored. His work passed into myth and his few early houses were changed and forgotten. But now, with a leading role in Rem Koolhaas’s Elements exhibition in Venice, as well as a show of his work at the Liverpool Biennale, Parent is having a bit of a moment. His history is rather paradoxical. He worked for Le Corbusier but never qualified as an architect. His radical ideas led him to be known as the “Supermodernist” and he was revered by the generation of 1968 as a maverick and lone genius, yet he refused to be associated with the student uprisings – indeed his acrimonious split with former partner-in-theory Virilio was caused by Parent’s refusal to join him on the barricades. And this most unusual and original of architects ended up designing massive, clunky nuclear power stations and alienating himself from exactly those radicals who had once seen him as a hero. Perhaps that paradoxical nature, the idea of an architect of ideas who embodies the grand aspirations of modernism but also managed to get things built, appeals to Koolhaas and to architects who have become impotent in the face of increasing specialisation and the generic corporate language of contemporary commercial design.

Drawings by Claude Parent, 2013 Certainly the buildings Parent did realise constitute an extraordinary oeuvre from what now seems a very different era. His early houses present a postwar world of confident, even fierce modernity. At times they recall Le Corbusier or Niemeyer, at others they evoke the ridiculous Arpel Villa in Jacques Tati’s 1958 film Mon Oncle. But occasionally they also thrill. The beguiling Maison Drusch (1963-65) at Versailles has one block stuck in the ground at an angle, as if it had fallen from a spaceship, while the incredible Maison Andrée Bordeaux Le Pecq (1963-65) in Normandy revels in a roofscape that anticipates Jørn Utzon’s Bagsvaerd Church and uses concrete with an elegant delicacy that escaped Corb himself. Most remarkable and famous however was the church of Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay in Nevers (1963-66). If much modernism is condemned for looking like a concrete bunker, that would have been the highest praise for this strange structure. It was inspired by the Atlantic forts built by the Germans during the Second World War, massive monolithic structures that impressed the young Virilio (who had grown up on the coast in Brittany). The architects had been impressed by the way one ruined bunker had begun to subside into the sand at an angle, tilting its floor, and by the cracks that had riven the concrete, letting light into the gloomy interiors. Virilio’s passionate exploration of what he called “bunker archaeology” proved hugely influential and Sainte Bernadette du Banlay was its apex, an almost frightening, alienated architecture, seemingly sealed and impregnable. In fact it’s split down the middle (an echo of the ruined bunkers) and this fissure admits a sharp, numinous streak of light, a crack in the clouds. In Nevers we can also see how the traditional elements of architecture disappear. There is no difference between wall and roof and even the floor seems to meld into a seamless mass. There is nothing like a traditional door and no windows. It is radical architecture from a moment when the Church was commissioning some of modernism’s finest moments; comparisons with Ronchamp are not off the mark, though there is little search for the romantic here. In a curious episode which indicates Parent’s lack of acceptance by the mainstream avant-garde (and the mainstream avant-garde’s conservatism), both he and Virilio were invited by Peter Cook to talk at a conference in Folkestone in 1966, when most of England had its eyes on the World Cup. The two architects turned up clad French intellectual-style in black, head to toe, toting pictures of their Nazi-bunker-inspired church at Nevers. The Brits (and the others) reacted badly to the Nazi imagery and booed them off with Heil Hitler salutes. Yet Parent kept popping up.

Parent’s drawings can be seen at the Liverpool Biennale After he split from Virilio in 1968, he continued exploring obliquity and his most explosive exposure came at the 1970 Venice Architecture Biennale where the architect constructed a landscape of ramps, slopes, neon-grid ceilings and sculptural planes that turned the French Pavilion into a sci-fi/expressionist cocktail of Dr Caligari’s Cabinet and Tron. The slopes were there to be lounged on, the steep inclines to be climbed; walls and floors melded into one. As a student I always thought Libeskind, Hadid, Himmelb(l)au and the other decons were a little half-hearted. If elevations were spiky and skewed, why should floors be level? It was the sections that gave these buildings away as cop-outs. All that rhetoric about disorientation and the smashing of bourgeois comfort zones – Parent did it better than any of them, and two decades earlier. Parent is back in Venice now. He has a small corner to himself in Koolhaas’s exhibition in the Central Pavilion. His ramps and wedge-shaped seating, the slanting floors with squidgy surfaces and some cardboard cut-out figures (a replica of his own one-time Neuilly living room) are lounging opposite the ramp and accessibility codes pioneered by US war vet Tim Nugent. Koolhaas, you sense, is enamoured of the challenge, the plane that gives resistance. Level floors are easy, ramps are for real theorists. And, of course, it was Rem who revived the ramp in his magical Seattle Public Library: architecture reimagined as pure ascent. Parent is also getting the chance to recreate more oblique landscapes, designing an exhibition for Tate Liverpool’s Wolfson Gallery during the city’s Biennale. Among the works will be his own exquisite pencil drawings of sloping cities and angled architecture. The designs still look strikingly utopian, as if we hadn’t caught up yet. “Architecture,” wrote Parent, “will once again be a part of the domain of self-evidence. It will be indisputable, undisputed. It will remove itself from the domain of the vanguard. It will just be. Mankind will acknowledge it as a part of itself. The other arts will once again find in architecture coherence and reality.” Which settles that. And is why you should see it. This article was first published in Icon’s August 2014 issue: Venice Biennale, under the headline “Marx and angles”. Buy old issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this |

Words Edwin Heathcote

Images: Claude parent and Emmanuel Goulet |

|

|