|

Ofunato Civic Centre and Hall, also known as Rias Hall |

||

|

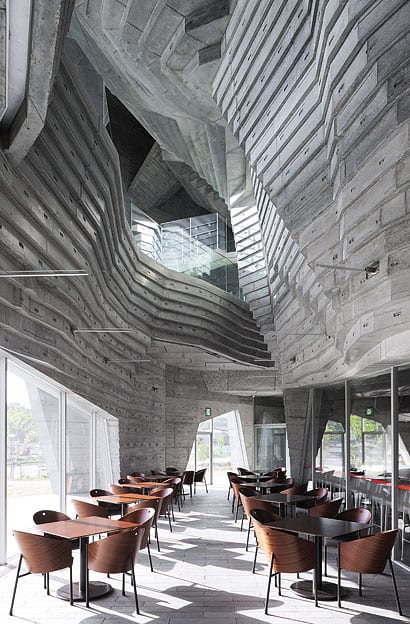

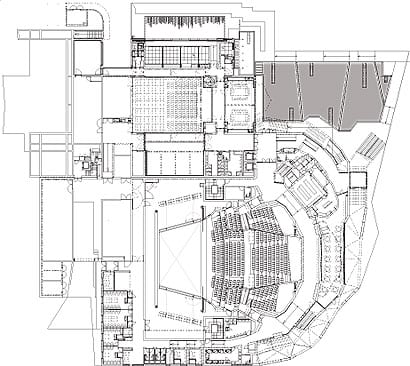

“About eight years ago I was about to give up.” A rare pause interrupts Chiaki Arai’s incessant torrent of words. “I was 52 and on a losing streak. So I went to see Frank Gehry, and saw his big factory full of people making crazy things. He told me to relax, to endure. And now I’m winning every competition.” Arai beams with satisfaction as he casts his eye around the cavernous interiors of the first building to be completed from that winning streak, the Ofunato Civic Centre and Library, also known as Rias Hall. We are in Ofunato, a town on the scenic Sanriku Kaigan coastline of Iwate prefecture, in northern Japan. I am here with Arai and Sou Fujimoto, observing the recording of a conversation between the young star and the elder stalwart by Tokyo Gas, an energy company that is carving out a role as a patron of architectural culture in Japan. The building is a remarkable tour de force for a man who had all but given up. Combining a 1,100-seat opera theatre and concert hall, an extensive library, a number of large flexible exhibition, rehearsal, and workshop spaces, a recording studio and a diminutive teahouse, the building is a bastion of civic culture. The diverse functions are combined into a hefty concrete volume, which rises in craggy masses above the surrounding town, echoing the mountainous landscape beyond. Inside, the building is part-cave, part-labyrinth, robustly geological in character and animated with unexpected glimpses into other spaces through walls and floors. The spaces of the foyer in particular are extraordinary, achieving a coiling Piranesian quality, rising through multiple realms of finely layered, overhanging concrete, supported by oddly angled flying buttresses and lit from hidden apertures high above. The interior has something of the atmosphere of a natural grotto in a rocky seashore.

The interior has the feel of a natural grotto in a rocky seashore The geological metaphors are explicit, conscious references to the local landscape. The coastline around Ofunato is famous in Japan for its dramatic scenery, with narrow inlets and rugged outcrops eroded by the waves into arching formations. Motifs referencing this scenery appear here and there in the architecture, from the skewed apertures of the exterior wall that wraps the foyer to details in the fixtures and lighting. The name of the building itself, Rias Hall, is drawn from “ria”, the geomorphological term for this type of indented coastline. These local meanings abound in the concert hall, the heart of the building. Designed in close collaboration with eminent acoustic consultant Nagata Acoustics, the design of each of the elements fulfils both an acoustic function and a semantic association. Waves of blue seats lap against heavy grey walls of textured concrete. Large cantilevered trays loaded with more seats overhang the sides of the space like rock formations. The ceiling is covered in clouds of faceted white reflection panels. Each seat, Arai tells me enthusiastically, has been precisely positioned for the best possible acoustics. But this overload of design justification just washes off me. It is the strength of the space overall that impresses. This combination of semantically loaded figuration with powerful spatial atmospherics is a clue to the formative experiences of its architect. Chiaki Arai is not particularly well known, even in Japan. But he has a unique and fascinating provenance, having studied at the University of Pennsylvania and worked for Louis Kahn in the early 1970s, then moving to a stint with the Greater London Council and soaking up the conversations of Leon Krier, Charles Jencks, Bernard Tschumi and Rem Koolhaas at the Architectural Association during the ferment surrounding the birth of postmodernism. The architect, who has just entered his 60s, has been quietly prolific, shaping a swath of Japan’s public architecture over the past three decades. His success in gaining commissions for regional cultural centres, such as at Ofunato, is a real David and Goliath story – an independent architect singlehandedly competing against the formulaic product of the large construction firms that dominate this sector. Leafing through Arai’s portfolio, however, and comparing it to what he has wrought at Ofunato, there is little sense that you are looking at the work of the same architect. His earlier work could be unsympathetically labelled as “earnest PoMo”, a collage of historicist forms and techniques in modern materials, with symmetrical plans, structurally ornate domes and figurative ornament. The crisis of confidence that prompted the meeting with Gehry, and his subsequent liberation from his former design language and scruple, seems to have unleashed a wave of vigorous creativity in Arai. With the completion of Rias Hall, and the attention given it by younger architects such as Fujimoto, marks for a kind of late arrival for Arai. This recognition, prompted by the formal originality of his recent work, is drawing attention to Arai’s design process, one that he has been developing for decades. Like an architectural mille-feuille, both the building and the method of its construction are defined by layered complexity. The intricate stepping formwork for the concrete layers sometimes took six months for each pour, and it was two years before the basic structural concrete shell was complete. The process also involved an exhaustive process of consultation, with more than 90 community meetings taking place over a period of five years. In these meetings, the design evolved from a simple collection of blocky forms to its final sculpted shape. Arai explains: “The proposal we made for the competition doesn’t look anything like the final building. After we won the competition, we held workshops with the local townspeople to completely redesign the building afresh.”

The intricate stepping formwork took two years to complete Ninety meetings! Each requiring a nearly five-hour trip from Tokyo. Project architect Masatoshi Naito told me that he had made the trip 600 times during the course of the project with only the faintest flicker of weariness. The importance that Arai places on public participation in the design process arises partly out of an authentic concern for the ideals of participatory democracy. In Japan, local communities have usually lain back and thought of nation and emperor while the machinery of the centralised state had its dastardly way with them. But the Sisyphean effort that his office puts into this process hints at a more specifically architectural motivation, closer to Arai’s heart: how to create an architecture that overcomes the homogeneity and sterility of construction-state modernism, and foster locality and community? Arai explains that these consultations achieve many things. They draw out and foster what he calls topophilia, the love of place, in the community. Each of the various spaces in the building is carefully discussed, and a collective “storyline” is produced that links these spaces into a coherent entity, like scenes in a storyboard. The workshops build a constituency of supporters for the project and reveal local images that can be incorporated into the design, lending a regional distinctiveness to it. But since the Ofunato project, it is the unpredictability, the contingency, introduced into the design process by such procedures that is now most compelling to Arai the architectural implications of which he is now exploring. “Inconsistent inconsistency” (a phrase which has considerably more grace in Japanese than in its English translation) is how Arai describes the goal. “Modernism flowed in two distinct streams,” he explains. “One approach, represented by Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, is to create ‘consistent’ spaces that can be applied the world over. The other stream, embodied by Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Kahn, is to give each structure an originality and local roots, resulting in the individuality of each piece by creating ‘inconsistent’ spaces.”

The entrance foyer, with a translucent fibreglass ceiling Arai’s next project, the Yuri Honjo Cultural Facility in Akita prefecture, to be completed in 2011, is about twice the size of Rias Hall, and pushes this wilful inconsistency to another level of complexity. The workshop-based design process has resulted in plans in which structural paths do not line up, resulting in a complex web of structural walls and struts. The resolution of this complexity is being achieved in his office by a kind of “parametrics by hand”. Arai’s desire to achieve critical density of social activity results in a kind of cornucopia of civic elements packed together in an enormous casserole of a building, like a kind of “mother ship” of public functions landing in the boondocks of rural Japan. He even cites the Death Star from the film Star Wars as part of the inspiration for this latest work. Arai is famously voluble. He seems to want to capture everything in the net of his attention.This immense appetite is also there in the vigorous enthusiasm of his architecture, in his excited advocacy of “inconsistent inconsistency”. The challenge now is how to distinguish this from chaos.

The dimly lit tea room, with LEDs behind a brass screen

The restaurant, with coast-inspired cliffs

Each seat in the hall has been precisely placed to aid the acoustics

|

Image Sergio Pirrone

Words Julian Worrall |

|

|

||

|

90 meetings with residents |

||