|

|

||

|

The founder of BIG is revamping and extending a Danish zoo in which the humans will be confined and the animals roam free. Talking from New York, he explains the project We had some unfinished business in zoos. We’d earlier won a competition to design a circus and zoo in Chongqing in south-west China, and were really happy with our design, but it was just before the 60th anniversary of the People’s Republic, so they went on a two-week celebration binge and awarded the commission to the third place, a local Chinese company. I think there was some fraternisation going on … When we were invited to work on the Givskud project, the zoo’s director, Richard Østerballe, told us that its approach has always been to have only social animals that can live together in larger groups. A lot of animals don’t, so end up incarcerated and alone – if you give them too much space, visitors can never see them as there’s often only one. Social animals can have much larger areas, so you’ll be able to enjoy them in a more natural setting, even though they are roaming around a sizeable territory.

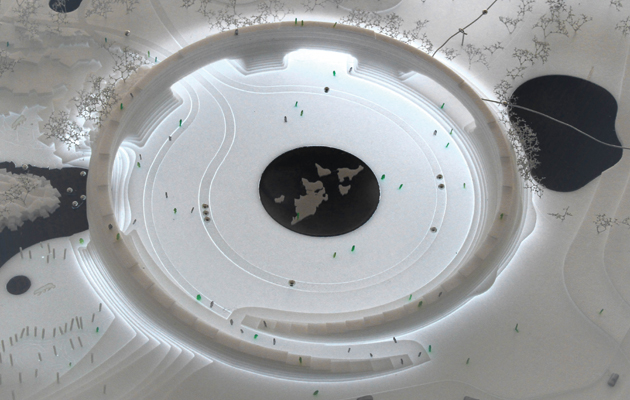

Bjarke Ingels, who appeared on the cover of Icon’s Zoos issue In a way, the job was to create a zoo that was designed on the animals’ terms, and at the same time try and undo the visual evidence that you are in a manmade environment full of walls, fences, moats and small caretaker buildings. We came up with a masterplan that drew on this zoo’s origins as a lionpark in the 1960s. The idea back then was that the private car allowed you to get close to the animals in an environment that was familiar – the surreal nature of sitting in your family car with lions right outside strikes me as a pretty cool concept. Givskud had developed a mixture of the car and walking to enjoy the animals, so we have built on this for our plan – at the moment this is only a guide, based on principles rather than precedent, which will be realised gradually as funding is raised. The main planning intervention is the arrival crater, where you can stroll around the rim and look out at different continents – Asia, the Americas and Africa – in which the animals will be reorganised over decades, almost like a migration. The crater acts as the end of the human world, and from then on everything is on the animals’ terms. It was a little bit inspired by the movie King Kong. |

Words Bjarke Ingels

Images BIG

Above: From the arrival crater you can look upon the zoo’s three “continents” |

|

|

||

|

The arrival crater with exits to the zoo’s three continents |

||

|

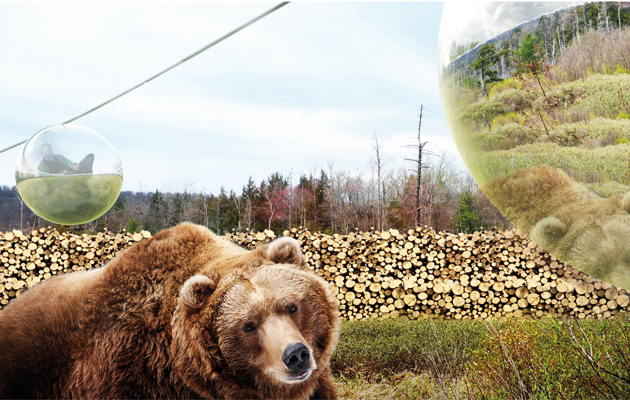

The villagers live in a typical native jungle village, but then they have this humongous wall with a giant gate, which is clearly a gate into something else – the wild jungle where King Kong lives. And we like the idea that the crater starts on the ground and coils around itself, rising up to incorporate the buildings that relate to the zoo and the arrival process, and you can also walk around the edge of it, more like an inhabitated land arc than an actual building. But it starts at the human scale at one end, then grows to become the gateway into the wild. You realise that you are preparing to go and explore something that is not part of your normal existence. The success of the bicycle has been quite remarkable in Danish urbanism over recent decades – people take bicycles more than any other way of getting around, so in that sense it’s almost like second nature. We thought we could take advantage of this and make Givskud a uniquely Danish experience, where you would propel yourself with pedals in the water, or on air, or on land. It’s not like you are just being dumped on a train – you actually move around autonomously within certain guidelines. We created a little catalogue of experiences – almost like an inventory of different separation systems. Some animals, all you need is a dent in the road, and they won’t pass, and others, like wolves, can really jump high, so you have to choose different means of separation for the various species. We foraged through the Danish landscape and found environments that are quite similar to the natural habitats of some of the animals – for instance, we have these massive wandering dunes in the north of the country that look like the Sahara, so we just started collaging camels into Danish sand dunes. |

||

|

Small pedalos provide transport through Asia |

||

|

A lot of the things that have happened in Copenhagen over the past decade, and also in New York, are focused on making cities more like habitats or manmade ecosystems, reintroducing nature and flora and fauna into the urban environment, so that gave us some kind of basic architectural discourse to apply to the art of making a zoo. As a result, all the architecture in the zoo, instead of referencing the human world or clichés of exotic countries like Chinese pagodas or African clay huts, will be somehow integrated into the landscape, with turf flowing over the roof, or nested between some rocks. We’re taking this idea that when you’re in a city, you integrate the trees on the conditions of the city, planting them in alleys alongside the roads between parking spaces. We are just swapping it, so we create a natural habitat with all of the city elements integrated, reversing the priority. And I think maybe that is what people want and expect today. Zootopia will contain all the accommodation necessary, but it will be an outdoor experience. When we did the Shanghai World Expo in 2010, I was reading Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City, a book about the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, where they invented the Ferris Wheel. What struck me was that, back then, these world fairs were literally a way for people to experience the world, perhaps to see pygmies or bellydancers from northern Africa. They couldn’t see it on television and they couldn’t travel there, so it really was a moment of wonder. |

||

|

Bicycling through Africa, concealed in a mirrored pod |

||

|

Today, people see amazing programmes on National Geographic, and they have probably also been on a few holidays where they saw real animals in their actual habitats. In that sense, although zoos remain important for education and research, to ensure an interesting experience they need to be more than just the passive consumption of a premeditated experience. At Givskud, instead of eating a prechewed meal, you’re moving around on your own, and because the whole zoo is based on social animals, and is much bigger than the typical zoo, you never stand outside some bars looking in at an incarcerated cat all alone in its cell. You will always be encountering a larger group of animals enjoying something much, much closer to their natural way of life, interacting with each other and prowling around. But that also means that, as a visitor, you will have to move around yourself. That’s where the bicycles come in again. You travel around then you get off, stroll about in a different setting with different security measures, then remount and continue on your way – it becomes a more individual experience. We also looked at expanding the zoo experience – Givskud had already started experimenting with allowing people to sleep in a hut in the wolf park, so we are trying to expand upon those ideas of what you could do with or in close proximity to the animals, so it becomes less of a premeditated, prepackaged experience, and more like real, live interaction with the animals. Urbanism is the art and science of reconciling differences. If you take the city, it is a physical experiment in accommodating a lot of different people from a lot of different backgrounds, age groups, religions, income levels, genders, sexual orientations, whatever, into a limited amount of space, in a way that maximises the freedom for each individual without inhibiting that same freedom for other individuals. Everything we do, from traffic planning to residential architecture to workspaces and parks, is an attempt to maximise the quality of life for all the different individuals. No situation is more extreme than a zoo, with the added difficulty that you can’t speak to the animals, but reconciling differences in a constructive way is really what Zootopia is all about. |

||

|

View of the arrival crater from above |

||

|

If you visit Givskud today, you’ll find it’s a pretty goddamn good zoo, and its intentions are admirable. The goal we are pursuing here is to make it even better for the animals. I think, in a way, we owe our humanity to the fact that we started investigating science and animals. Certain geologists refer to the era that we live in now as the Anthropocene – a geological era in which the main influence on the transformation of our planet’s geography is human. We dam rivers, contribute to global warming that causes sea levels to rise, we domesticate animals and plants – our power to influence the planet in a very real way is indisputable and, as Stan Lee taught us, with great power comes great responsibility. It’s not even a choice to leave nature alone – in a way we do need to take responsibility for it, so we also have to make sure we understand it. The second we became architects, started building buildings, laying out the fields and so on, we no longer evolved purely by adapting to our environment, by finding caves we could inhabit or trees we could climb. In a way, we reversed it and started evolving our planet by adapting it to our life, which is a pretty amazing thing, but it’s a power that has to be wielded with a great sense of responsibility. In that sense I think there is still a role for zoos – you can see animals in as good conditions as we can provide, we can study them, and kids can realise that they are not just something on television. Even though the Givskud project is “zootopian” in its ambition, we just have to do as good a job as we possibly can. Like all projects, you start by setting the bar, then you work with the available means to try and meet those objectives. This article first appeared in Icon’s February 2015 issue: Zoos, under the headline “Zootopia”. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this |

||

|

A zip line over the Americas allows its animals to be viewed from above |

||