|

|

||

|

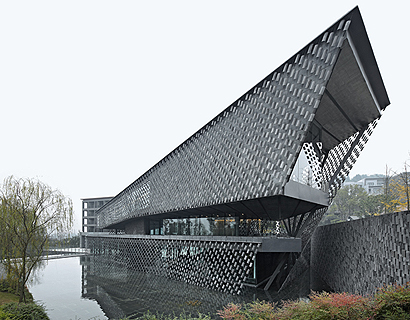

The Xinjin Zhi museum in Chengdu, in south-western China’s Sichuan province, is an exhibition building dedicated to Taoism located near the base of a mountain of holy significance. Sombre, and constructed mostly from steel and concrete, it is surrounded by veils made of thousands of traditional clay tiles held along thin gossamer wires. The building is intended to evoke various concepts of importance in the Taoist tradition – nature, balance and the reconciliation of opposing forces, for instance. The exhibition spaces within are continuous, looping from the darkness of the basement to the light of the third storey, from where there are views of the holy mountain. The circulation spirals around, with the building envelope responding to various site conditions – formally, it recedes from a large bulky building, apparently breaking into separate blocks as it does so. To the square from which the museum is accessed it presents a flat facade, while to those on the road that swings past at second floor level it presents a twisted, curved aspect. Two large, reflecting pools surround the structure on different levels, helping to cool the building, but also playing to the symbolic value of nature – and specifically water – in Taoism.

credit Daici Ano By far the most impressive part of the building is the tile screen, which appears in three different guises – almost solid at the basement level retaining wall, almost stacked at the tea house on the second floor, then appearing with a pixellated pattern across the main facades. It serves several functions: pragmatically, it acts as a solar shading device, creating pleasant interior light and lessening solar gain; it also allows for areas that are both external to the envelope and seemingly inside, owing to the impassibility of the wall. The screens also symbolise a release of weight – or an “increase in lightness” as the project architect explains: “We wanted to make the wire as thin as possible, which was challenging, but it was strong enough.” The super-taut wires render the supports near invisible, resulting in gentle wave shapes across the facade that are intended to give the impression of the tensile structure being in seemingly effortless repose. This building is reminiscent of Benedetta Tagliabue’s Spanish pavilion for the Shanghai Expo of 2010 – both are Chinese buildings by foreign architects that create a feature or a permeable facade through reinterpreting a local craft culture. But it is also typical Kengo Kuma, which is one of the most interesting Japanese practices working at the moment, with a wide variety of projects ranging from cafes to full-scale commercial projects. With a very contemporary take on certain themes of postmodernism, such as historical reference and local culture, the practice has been creating buildings that dazzle with the ingenuity of their surfaces, materials and structures. The prospect of it achieving the same standard on British soil with its V&A museum in Dundee is tantalising.

credit Daici Ano |

Image Daici Ano

Words Douglas Murphy |

|

|

||