|

|

||

|

The retail mega-project shuns the sterile indoor mall in favour of a low-density streetscape and Make’s elegant brick hotel Chengdu is China’s fourth largest city, with a population of 15 million, and among its richest. Its economic growth – as a high-tech gateway to the huge western provinces, and to India, Myanmar and beyond – has long outpaced Beijing and Shanghai. Its reputation as a commercial and cultural powerhouse, with an attractive lifestyle and temperate climate, is matched by the speed and range of construction. In particular, Chengdu has topped global lists for new shopping centres for almost a decade – Steven Holl’s Sliced Porosity Block is one among many. And there have been mistakes: the stalled New Century Global Centre (“the world’s largest building”) has been an embarrassment for all concerned, while last year’s IFS (a huge luxury mall in the Hong Kong mould) is a shiny, sterile experience. However, right alongside the latter, but taking a highly contrasting approach, is Taikoo Li. Local government, developers Swire and Sino-Ocean, and architect Oval Partnership have all collaborated to maximise the potential of this highly desirable site in Jinjiang, Chengdu’s business and retail centre. The demanding realities of modern retail are combined with recreated lane patterns and preserved buildings to provide an intelligent, low-density alternative to the standard indoor mall.

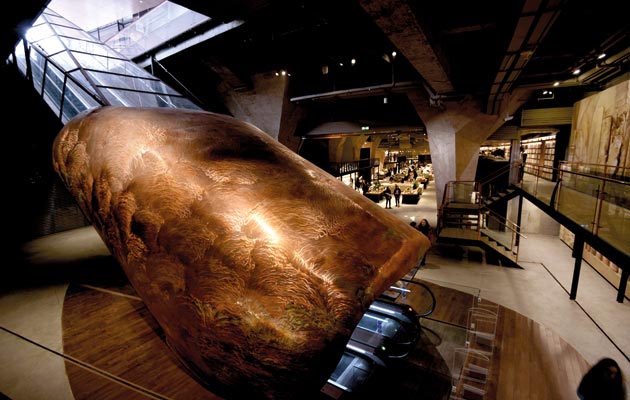

The main entrance down to the Fang Suo bookstore, impressively styled by Taiwanese designer Chu Chih-Kang An open, ungated pedestrian precinct has been constructed from scratch around six carefully restored heritage elements, including the important Daci temple complex, which attracts a wide local audience, and Guangdong Hall, a meeting point for Cantonese merchants. These act as focal points around the edges or along the axes of a synthetic streetscape created from two-storey pavilions. The latter are designed to evolve, allowing future architects to create new elevations under the fixed roofscape. The entire development is divided into “slow lanes” for restaurants and boutiques, and “fast lanes” bordered by pavilions with larger floor areas to meet the demands of major brands, many lured to western China for the first time (alongside Muji’s largest overseas outlet). Below is an extensive underground infrastructure centred around a new metro station. This provides large floorplates for the cinema, supermarket and impressive 4,000sq m Fang Suo bookstore, as well as housing mid-range stores for commuters and 1,000 parking spaces to ease the pain of pedestrianisation. A 47-storey office tower and a mid-rise hotel, both by Make Architects, complete the development. The former, Pinnacle One on nearby DongDa Street, was completed last year and sold as secondary to the main scheme. Intrinsic, however, is the striking Temple House Hotel. Its form and materials are inspired by the two heritage buildings included within its ambit, which feature the long grey bricks, rich timber and tiled roofs typical of the region.

A “slow lane” between Taikoo Li and the Daci Temple complex One of these buildings, sited in the main Taikoo Li area, serves as a tea room and spa: hotel guests can walk across in dressing gowns, epitomising the unusually porous approach to the entire development. The other has been adapted as an impressive main entrance from the south, with a reception, library and art gallery. This leads on to a large, atmospheric courtyard created by two L-shaped buildings – a ten-storey block of guest rooms and a seven-storey apartment block, the heights dictated by sightlines for the temple. An outward-facing cafe and a more intimate bar futher Taikoo Li’s reputation for food and nightlife. The courtyard – a nod to traditional housing – is divided by a wide, low podium covering a double-height restaurant. Visitor facilities run across the site below ground, including a pool, gym, ballroom, restaurant and conference spaces. Many are given additional light and height by conical ceiling structures that rise up as peaks in the courtyard. These, and an eye-catching stepped staircase, reference the terraced fields for which the Sichuan region is famous. Further below are three levels of basement linking across the wider Taikoo Li development. |

Words John Jervis

Above: A restored courtyard building forms the main entrance to the two blocks of the Temple House Hotel

Images: John Madden / Make Architects |

|

|

||

|

The tea room and spa lie outside the main hotel area |

||

|

The outward-facing facades of both blocks are clad in a dense skin of grey bricks, echoing the unbroken walls of the heritage structures but using a three-dimensional weave of recess and projection, in conjunction with black stone lintels, to imitate local brocade techniques. This brickwork becomes increasingly porous to attractive effect around the generous plant level at the top. In addition, handmade bricks cover almost the entirety of all facades up to the height of the restored entrance building, punctured by small brass elements in patterns that echo the perforated brickwork of the spa. This sensitive use of material, and the blocks’ restrained height, provides an effective mediation between Taikoo Li’s low pavilions and heritage structures, and the diversity of buildings beyond its borders. Similar intelligence with materials is evident in the slatted timbers of deep terraces at the ends of each block, and glass walls on inward-facing facades. The latter are fritted to resemble bamboo shadows, responding to light in an agile manner and echoing traditional wooden courtyards. Internally, the availability of black granite has allowed for its extensive use, particularly impressive in rusticated blocks below ground. As a result, communal areas are generally dark, continuing the slate-grey theme from the exterior, with pools of light to provide warmth and direction. In contrast, rooms employ timber in a range of shades, as well as sliding panels and screens, emphasising texture and light. With the exception of the restaurants and bars, interiors have been left in the hands of Make, ensuring a coherent whole. Sadly, the contractors’ decision to slot bricks into their backing panels when the latter had already been placed on the facades was a mistake. Although this does make for striking deep recesses, even on brief inspection imperfections inappropriate to a high-end development are visible, whether in the uneven quality of the overall effect, or the prominence of spacer stones, used in place of grout and still loitering between bricks. In addition, the belated insertion by local design partners of service doors, some with clumsy lintels, seems to have been undertaken in the belief that the uniformity of brick would conceal all. |

||

|

The hotel’s courtyard, with its raised light wells, looking back towards the restored entrance building |

||

|

This architecture is dignified rather than flashy – the hotel’s ambition is to express lifestyle not quest after luxury. For Make, it has been an important project and a learning process, demonstrating that the practice can deliver major projects with an enviable level of class in China. Yet, as indicated by similar issues at Holl’s Sliced Porosity Block, quality control remains a real problem for foreign architects in China, particularly for practices such as Make, for whom finish is essential to the desired effect. Taikoo Li is a high-risk venture for all concerned. Despite its imposing 74,000sq m area, only 110,000sq m of lettable space is spread across the 300 or so stores of its streetscape: eye-watering rents and short-term leases are inevitable. The success of Beijing’s Taikoo Li Sanlitun, the first development to explore this concept, also masterplanned by Oval, has calmed nerves and shown early concerns about weather and “undesirables” to be misplaced.

Screens and black granite are used extensively throughout the hotel interiors, here below grade In Chengdu, greater emphasis has been placed on access to walkways and greening of public areas. More importantly, there is the ambition that the precinct should fulfill the traditional role of downtown as a gathering point for the entire city, not just its brand-oriented youth, with long-term gains for all. In the eyes of its architects at least, the new public spaces, with their potential for organised events or general idling, are the greatest infrastructural gain of the entire process. Taikoo Li successfully bestows landmark status on a site suffering from aborted and inappropriate construction in the recent past. Inevitably, it is also a sanitised version of reality – the scatterings of hutongs and postwar housing blocks around its edges, described as eyesores in some evaluations, also fulfill the traditional role of downtown. Excising such diversity to milk the commercial potential of the concept would be a mistake. This article first appeared in Icon 148: Cities. Make’s building was on the shortlist for a 2015 World Architecture Award |

||