Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter

Tucked away on a quiet side street in a leafy area of Helsinki, Alvar and Aino Aalto’s discreet suburban home demonstrates a beauty and practicality familiar from their better-known designs

Photography courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation featuring Alvar Aalto in front of his house in the 1930s

Photography courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation featuring Alvar Aalto in front of his house in the 1930s

Words by Jessica-Christin Hametner

Behind an unassuming entrance, the Aalto House nestles into the hillside of Riihitie in Helsinki’s leafy Munkkiniemi neighbourhood. From the quiet residential street it might take visitors to Aino and Alvar Aalto’s iconic home-museum a moment to find the entrance. Yet it is exactly this modest simplicity that perfectly encapsulates the Aaltos’ humane approach to architecture.

When in 1934 the architect power couple acquired a site at Riihitie, the pair – who moved to Helsinki from Finland’s former capital Turku – began designing their own house, which was completed in August 1936. Envisioned as both a family home and an office, Aino and Alvar Aalto’s overlapping styles that blurred the lines between home and work were light years ahead of their times.

While Alvar shared the minimal, function-first philosophy of Bauhaus – its influence most evident at his designs for the Paimio Sanatorium completed three years prior to the young couple moving into their Helsinki home – the modern aesthetic of the Aalto House feels warmer and more intimate than his previous works.

Photography courtesy of Artek featuring Aino and Alvar Aalto

Photography courtesy of Artek featuring Aino and Alvar Aalto

‘I certainly wouldn’t describe the Aaltos’ early style as modernist,’ says Katariina Pakoma, senior chief curator of the Alvar Aalto Foundation. ‘The early designs were inspired by the neo-classical era but towards the end of the 1920s they shifted towards modernism. Their great international breakthrough came with the Paimio Sanatorium, but over the years the Aaltos’ style evolved and what we see in their home today is something quite different – it’s full of experimental details and lots of natural materials.’

This interplay of raw materials, most notably between brick and wood, is repeated both inside and outside. On the exterior of the building, the slender mass of the office wing is painted in white, lightly rendered brickwork, while at the rear of the building dark-stained timber cladding forms a high-contrast look above a south-facing terrace. While swatches of glazing enhance the connection between the living spaces and garden, the streetside elevation of the house is discreet and closed-off – a dramatic juxtaposition to the open design elements at the back.

Although the landscape was an integral aspect of the Aaltos’ approach to architecture, it belies the truly spectacular space that exists beyond: the home only begins to reveal itself inside, and as it does, provides an insight into the couple’s empathic design philosophy. Notably, the pair admired the Japanese sensitivity to organic forms, clean lines and honest expression of natural materials, which in the years to come would continue to inform the Aaltos’ own enduring designs.

Photography courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation featuring the main entrance of the house

Photography courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation featuring the main entrance of the house

On the ground floor, the varnished parquet flooring creates a seamless connection between a string of social spaces, including a living and dining room featuring a wealth of iconic objects, and an architectural studio that served as an office until 1955 before the team moved into the Alvar-designed building at Tiilimäki 20.

The embrace of natural materials and the subtle nod to Japanese design continues in the living room where wood-framed sliding doors, which are likened to Japanese fusuma screens, serve to separate or unite internal living spaces as needed. Seeking out more progressive practices, the dining room is wrapped in a sound- absorbing fabric that looks and feels like suede, while decorative chairs, bought by Aino and Alvar during their honeymoon to Italy in 1924, showcase a perfect blend of form and function.

The living room is equally filled with original masterpieces – a paper prototype lamp by Danish luminary Poul Henningsen complements the interior scheme, while Alvar’s beloved Beehive pendant light is centred above a coffee table with elegant, curved legs. However, the room’s pièce de resistance is the Aaltos’ iconic 400 Tank Chair. With its bent arms and striking zebra print – selected by Aino on a trip to Europe – it was created by Alvar in 1936 for an exhibition at the Triennale Milano.

Photography courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation featuring the Aalto House living room

Photography courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation featuring the Aalto House living room

In the studio, Aino’s original bench and sofa designs sit alongside architectural drawings, scale models and Alvar’s paintings. Providing new perspectives into the Aaltos’ personal life and Alvar’s lesser-known passion for painting, the studio highlights how art guided Alvar in his designs. ‘Although he never regarded himself as an artist, Alvar was a keen painter,’ says Pakoma. ‘He also made sculptures using wood, which allowed Alvar to experiment with wood-bending techniques that he could employ in his furniture designs.’

Running perpendicular to the living spaces downstairs, the three bedrooms on the first floor layer various textiles and Japanese-inspired touches to create a feeling of liveability. As downstairs, there is a continual awareness of nature, light and an embrace of organic materials. A rug in the master bedroom adds tactility to a practical linoleum floor, while delicate armchairs designed by Finnish designer Maija Heikinheimo create visual interest without overpowering the interior.

‘It’s a bit more modest upstairs,’ says Pakoma. ‘Even if this house is quite minimalistic, it is also full of interesting details. The Aaltos worked hard and gave attention to every detail of their home.’

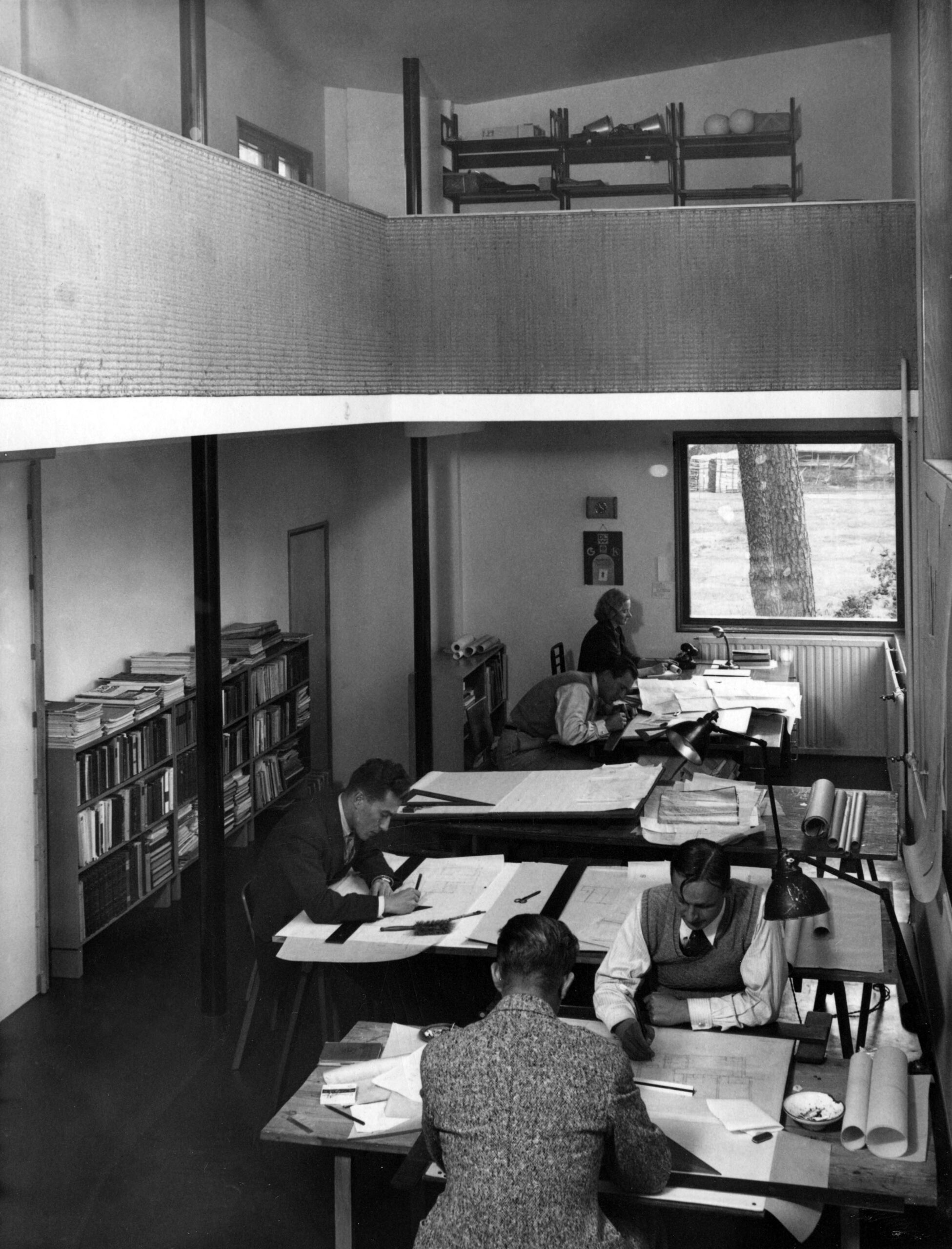

Photography courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation featuring the house’s office and studio in the 1930s

Photography courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation featuring the house’s office and studio in the 1930s

Recognising the role architecture plays in shaping human experiences, Alvar’s meticulous attention to detail is captivating. From the use of circular skylights in the corridor to maximise natural light to the sculptural doorhandles – originally designed for the Paimio Sanatorium – that loop inwards to avoid catching on sleeves, Alvar considered every part of the design to promote wellbeing.

Together, the Aaltos received significant recognition for their work, which spans architecture, furniture and glassware design. In this modest family home, however, another story unfolds – namely, the remarkable history of these Finnish architects whose creative output goes far beyond aesthetics. Breathing life and humanity into modernism, this home shows why the Aaltos’ work continues to stand the test of time.