Laban Dance Centre. Photo by Claire Saxby via Flickr

Laban Dance Centre. Photo by Claire Saxby via Flickr

At once traditional and avant garde, Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron are hard to define. And they’re certainly not shy of controversial work.

Herzog & de Meuron was founded by Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron in 1978 in Basel. The two became friends at only seven years old, and their career paths were closely parallel. They both started university studying degrees other than architecture and switched a year in, Herzog from biology and chemistry, and de Meuron from civil engineering.

Both attended Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, graduating as architects together in 1975. And both remained at the university as teaching assistants immediately after their studies, then founded their architectural partnership in 1978 in an office in Basel. Since the late 70s the studio has not grown to an office of over 120 people worldwide, with additional offices in London, Munich and San Francisco.

The studio’s impressive buildings often have an immediate impact with their unusual forms and textures. The duo’s work breaks the cliches of architecture, blends old and new, traditional with avant garde and they are not afraid of controversial work.

Read more: Interview with Jacques Herzog

In Britain, the studio is best known for the conversion of the huge Bankside Power Station in London into the Tate Modern, one of the world’s largest collections of modern and contemporary art and the UK’s third most visited attraction. The Tate opened in 2000, and was largely responsible for revitalising the South Bank area of London. Herzog and de Meuron won an international competition with a proposal suggesting the least changes to the original structure.

In 2016 Herzog & de Meuron were commissioned to undertake the Tate extension, initiated titled Switch House. The extension increased the galleries exhibition spaces by 60 percent and includes spaces for learning. Unlike the Tate Modern, which was contained within the framework of the old power stations form, the extension is has a twisted geometric shape, with folded facades.

The Tate Modern is also one of a handful of renovation projects the studio has undertaken. In these projects, the architects’ ability to combine old structures with completely unconventional forms, materials and textures is often impressive.

Other notable projects by the studio include the Beijing’s National Stadium, known as the Bird’s Nest, a dramatic structure that features a web of steel lattice work and which served as the main arena for the 2008 Olympic Games. The Stadium is also scheduled to be used in the 2022 Winter Olympics. Herzog & de Meuron also completed the de Young Museum in San Francisco, a project that involved the revival of an old museum that had been destroyed in an earthquake.

The studio’s VitraHause in Weil am Rhein, Germany, is also a notable structure comprised of twelve cube-like houses that jut out into an unusual three dimensional composition. The building is used as an exhibition space for Vitra’s furniture and the interiors were designed to mimic residential spaces.

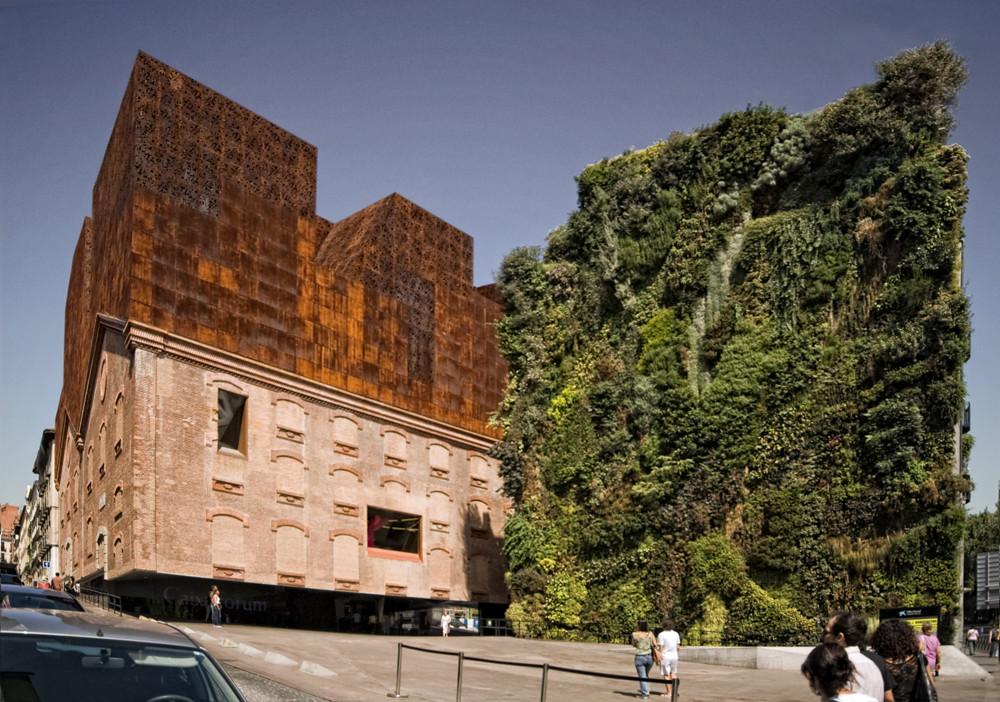

Herzog & de Meuron work closely with nature in built projects. The architects have a fascination with materials – informed and supported by extensive research they undertake – and textures. One research topic they pursue is into how mosses and lichen grow on the surfaces of stones. Living facades have been included in projects by the studio, including the CaixaForum in Madrid.

CaixaForum Madrid. Photo by Óscar Carnicero via Flickr

CaixaForum Madrid. Photo by Óscar Carnicero via Flickr

As well as built work, the two architects have embarked on several collaborations with artists, including Remy Zaugg and Ai Weiwei. The collaboration with Zaugg in 2001 on the lighting for his exhibition space informed the design of the Tate Modern.

Herzog and de Meuron were awarded the Pritzker Prize in 2001, the first time the prize was awarded to a partnership instead of to a single architect. The studio also won the Stirling Prize for the Laban Dance Centre in 2003, and were awarded the RIBA Gold Medal and the Praemium Imperiale in 2007.

Both architects teach at ETH in Zurich and at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.