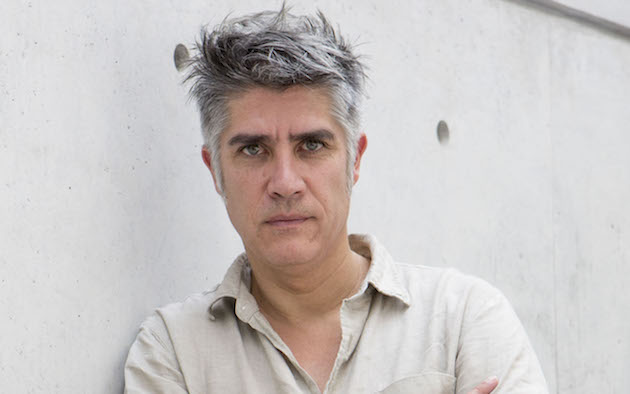

Pritzker Prize-winning architect Alejandro Aravena. Photograph courtesy Elemental/Phaidon

Pritzker Prize-winning architect Alejandro Aravena. Photograph courtesy Elemental/Phaidon

“Boldness is the fairest way to establish a dialogue with the massive forces of nature”, says the Chilean Pritzker-winner to Icon’s Matthew Ponsford

Alejandro Aravena was born in Santiago, Chile and graduated from Universidad Católica de Chile. Having abandoned architecture to run a bar, he was enticed back by the chance to design a mathematics faculty for his alma mater. He went on to build a string of public projects, including the monolithic Angelini Innovation Centre. Aravena met engineer Andres Iacobelli while teaching at Harvard University and the two founded Elemental, a practice that has built thousands of homes across Chile and Mexico, including its signature Half A Good House.

Aravena won the Pritzker Prize in 2016 and directed the Venice Architecture Biennale the same year. Following two years of creative glut, in 2018 Elemental is writing its own history, to be published as a monograph by Phaidon on 17 October. Aravena, who has made a habit of chewing up the questions that are put to him and coming back with a better answer to a different question, says it is less about influences and more about ‘conflicts’. He talks about what this means, the legacy of his Venice show, and how nature demands boldness.

ICON: Before the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, you said you wanted to create a space of learning for architects. Has that changed how you have worked since then?

Alejandro Aravena: We are now working on the new headquarters of the Inter-American Development Bank in Bueno Aires and that, originally, was [commissioned to be] a corporate building. Because it’s a development bank, the director wanted to trigger some of the benefits of the projects that they’re normally financing through their operations themselves, through their building. So he said, ‘We would like to have our headquarters in the middle of Villa 31,’ the biggest slum in Buenos Aires. Fifty-thousand people, across the railroads from the most expensive square metre in Buenos Aires – so, there are opportunities for the people living in the slum, but they can’t access them because it’s disconnected.

Seaside Promenade at Constitución, Chile by Elemental. Photograph courtesy Elemental/Phaidon

Seaside Promenade at Constitución, Chile by Elemental. Photograph courtesy Elemental/Phaidon

We thought, instead of asking for a pedestrian bridge [to link to Villa 31], why don’t we make the building itself the bridge? This idea of doing two things at the same time – in this case, infrastructure and building, and also on the bridge there is a park – came from Sergio Fajardo, the former mayor of Medellín [in Colombia, who spoke in Venice], and Medellín’s transformation of their water tanks into public spaces.

ICON: You’ve been very candid about the conflict that takes place at the start of your projects as you gather the different stakeholders for these community discussions. Is it right to say this kind of ‘participatory design’ can’t happen without fairly brutal conflict?

AA: And brutal honesty, I would add. In Buenos Aires, we’re also working on a project in La Cava, which is one of the most – what word to use – impressive slums I’ve ever been in. There’s no sewage system, so all of the pedestrian alleys are flooded by shit, basically. We went there

to understand how to intervene.

They are very well located in the middle of wealthy neighbourhoods, but with 15,000 people living under such conditions. There are drug-dealing issues that are complicated. On the other hand, people don’t want to be displaced, because that would be the end of the reason why they came to cities, to look for a better life, for opportunities.

You have to integrate all the actors: not just the end-user in the slum but the municipality, the federal government, the ones financing the operation, the wealthy neighbours. Fear or resentment, all those emotions that are involved have to be brought to the surface, so that you can have a clear picture of the complexity of the question, before jumping into the solution.

For a couple of days, we just sit there, shut up and listen. So that on the third day, we can say: this can’t be done on a micro-scale, it’s impossible to keep the fabric of this place, because of the septic wells that are underneath and have polluted the water basin. It will have to be remediated, at least 500 families at a time. Of course there’s friction. But in that conversation, and dialogue, everybody in the end was thankful.

ICON: You’ve been writing the history of Elemental. Did this give you a chance to rediscover early influences and think about where your ideas originated from?

AA: Not having grown up in an environment surrounded by architecture – I mean not just my family but also, in Chile (we did not have the empire they had in Peru or in Mexico) – I felt the need to swallow the whole body of knowledge of architecture. I studied from 1985 to 1990, which were the last five years of Pinochet, and not many magazines made it to Chile – we just had books. So, postmodernism didn’t make it.

I always tell this anecdote: in the first year of not knowing about architecture, I guessed that the names you were given were the ones that were apt to follow. So Corbusier, Mies, Vitruvius or Palladio, these were the big names. And then there were other names, like [Hans] van der Laan, the Benedictine monk. Well, if I’m reading van der Laan in the first year, he must be one of the biggest names in architecture – that’s why I’m being told about him. I went to university in Venice in 1992 and I wanted to see the original of van der Laan’s manifesto, Architectonic Space. And I was the first one to have ever taken the book off the shelf!

The Ocho Quebradas House by Elemental. Photograph courtesy Elemental/Phaidon

The Ocho Quebradas House by Elemental. Photograph courtesy Elemental/Phaidon

And so, we were looking at architecture that had stood the test of time, but I couldn’t possibly know if those were the right names to look at or not. Some of the professors were showing us Portuguese architects, who were closer to our reality. It was nonsense to look at the high-tech, or the postmodern, in a poor environment like Chile. But the Portuguese, I guess they were closer to what we could then deliver [in terms of] quality. I remember having a book by [Eduardo] Souto de Moura on the table, which had been brought in by one of our professors. So, instead of postmodernism, Souto de Moura was on our desk. I was there doing the numbers the other day, and Souto de Moura, at the time, was 28.

I would say that in the end, the biggest influence has to be Louis Kahn. Not his writing – I don’t understand a thing he writes – but the buildings, the treatment of matter.

ICON: But after that, you quit…

AA: After swallowing the history of architecture, I had one shitty client after another, connected to real estate. Not wanting to improve the quality of life through the built environment, but to make a profit. If it was more profitable, they would have gone to the stock market. I thought, I didn’t study for this. And I didn’t feel I had enough strength to resist that lack of quality, so I quit. That’s why I was running a bar. If I’m not going to be able to produce something decent, I prefer to do nothing.

The Angelini Innovation Centre by Elemental. Photograph courtesy Elemental/Phaidon

The Angelini Innovation Centre by Elemental. Photograph courtesy Elemental/Phaidon

ICON: With the Buenos Aires bank, the housing projects, and the rebuilding of the whole city Constitución in Chile after the 2010 tsunami, you talk each time about building with nature. Why focus on nature?

AA: I guess it is a mix between being humbled by nature and being required to be bold by nature. I don’t know if you have had the experience of being in an earthquake above eight [on the Richter scale]. You can’t stand on your feet. I mean, the earth becomes liquid. Unless you’re really stupid, it’s very easy to understand that there are things out there that are much bigger than you.

So, these are very obvious forces – there’s one less obvious, and that’s gravity. Recent architecture wants to be light. You take a glass building – it’s several thousand tonnes, and we are [trying to make] ‘light’ architecture? I think celebrating several thousand tonnes is so much more important than making it appear as if that weight is not there. I’m thinking about the Angelini Innovation Centre, for example, where the structure is the building.

And beyond that, maybe even less obvious, is time. That structure will last, even with the earthquakes we have here, I don’t know, 500 years? That can’t be achieved through a shy approach. It’s just pathetic to do something that will collapse under an earthquake. Boldness is the fairest way to establish a dialogue with the massive forces of nature.