|

|

||

|

Fumihiko Maki’s Aga Khan Museum of Islamic Art and Charles Correa’s Ismaili Centre are intended as places of “civic encounters” with other communities, yet are set in a formal garden miles from Toronto’s other cultural institutions. Can Maki’s beautiful fortress and its refined grounds lure visitors all the same? This article was first published in Icon’s October 2014 issue: Museums, under the headline “Act of faith”. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this Two new buildings poke out of Toronto’s leafy Don Valley, about 13km north-east of downtown. If you drive by at speed, the view lasts a few seconds. The one that looks like a moon fort is Fumihiko Maki’s Aga Khan Museum of Islamic Art, and the other one is Charles Correa’s Ismaili Centre. Connecting them are gardens and a park by Vladimir Djurovic. Toronto’s Moriyama & Teshima Architects were the local architects. Even from the highway the scene hums with quality and expense.

The museum is clad in white granite with a metal roof Correa won the competition and construction drawings were underway when the adjacent property became available. The new land already included John Parkin’s Bata Shoes headquarters, a white rectangle from 1965 that floated on pilotis, like a Mediterranean hotel. Sasaki and Associates added the museum in its 2002 masterplan, and Maki further developed it in 2005 with a formal Persian garden. The Bata building was demolished in 2007 after a repurposing study and despite local protests. “There wasn’t a museum dedicated to the different civilisations of Islam,” explains my guide, Azim Alibhai, and nowhere to “see something from Spain juxtaposed with something from China”. Building the museum in Canada was a natural choice because “Canada is a model for pluralism”.

The windowless angled walls create the impression of a fortress The Ismaili community has been established in Canada since thousands arrived after their expulsion from Uganda by Idi Amin. The Aga Khan, the hereditary imam of the Ismailis, writes that “after 1972, we decided to build new spaces for the gathering of our communities and for the practice of our faith in the countries that were welcoming us … Structures where we could receive other communities and institutions in a dignified manner, and where we could demystify our faith.” The first such centre was designed by Hugh Casson in London near the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1985, and the second in the west was a gentle building by Bruno Feschi for the Vancouver suburb of Burnaby.

Concrete paving and planters match the granite exterior Feschi calls his centre “an iconic place for the civic encounter”, but today’s Canada is less civil and less pluralist than the one he built for. An oil boom and eight years of right-wing government have changed the tone. Inequality is rising; we now imprison foreigners, mostly Muslims, on secret evidence and spy on aboriginal activists and environmentalists. The only images of people in our redesigned passports are of white male industrialists, soldiers and sporty kids. In this context, the AKDN’s investment in international dialogue based in Toronto is praiseworthy before we even get to the architecture, but the project also raises the question of where civic encounters take place today. Once, it would have been in the streets, but now it is logical to build private homes for them.

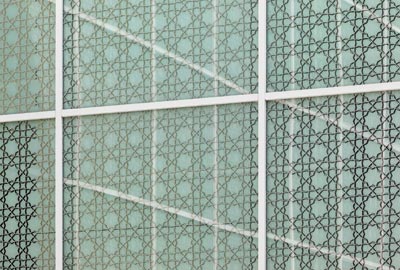

The glass is patterned with Islamic motifs And that being the case, where should these buildings go? The Don Valley site was a practical choice for the Ismaili Centre – the Ismaili National Council has rented offices in a nearby tower for over 20 years, and it is well served by highways and bus transit. But the museum was added because there was an opportunity. It would have been a more confident act to build a world-class museum of Islamic cultures downtown with the other leading institutions. While it was luck that made such a large site available, now the complex must rely on intention. In a region with few pedestrians, nobody will wander in from curiosity as they would downtown, where we could also compare Maki’s beautiful building with Frank Gehry’s Art Gallery of Ontario or Daniel Libeskind’s Royal Ontario Museum and tear those two down with our teeth.

The plastered interiors have an extremely high quality of finish Arriving by car reduces the force of this comparison. Seen from Wynford Drive the museum’s fortress profile is initially deceptive. It stands guarded, set back in a landscape lesson in modernist planning; a strip of office parks on one side and an eight-lane highway on the other with residential zones of newer condo towers and older townhouses further in the distance. Only two large windows interrupt the glacial sweep of its white granite walls (angled to catch the light, they would also help in a siege), while pairs of hexagonal skylights suggest crenellations and a metal auditorium roof rises beside the entrance with a watchful, Cylon-like countenance. Two crucial decisions dramatically improve the approach to the site. Both were expensive. A 600-car garage was built underground and more than 1,000 mature trees have been planted, including tall redwoods, decades-old magnolias, and berry trees to attract birds. The white concrete paving stones, benches and low walls were matched to the granite of the buildings and to contrast with the pearlescent black reflecting pools. The formal garden is remarkably peaceful considering its proximity to traffic. It backs into the park, a new green corridor joining Wynford Drive and Eglinton Street that includes about 2km of public paths. |

Words Lev Bratishenko

Images: Imara (Wynford Drive) Ltd. |

|

|

||

|

Light from the atrium casts patterns on surrounding spaces |

||

|

From the black pools you head left to the museum or right to the centre, which can’t be entered from the garden even though its prayer hall makes a dramatic intrusion there: a glazed wall, backed by onyx, beneath the faceted dome. This is the qibla wall. In a good mood, it is mysterious, but it is the back of the building and there is something uncomfortable about the encounter. Originally it was transparent, but condo towers built during construction were visible from inside the hall and forced a change. Gawping pedestrians may have eventually had the same effect. The museum’s glass doors sit below a razor-sharp aluminium canopy and lead to a courtyard within a 10m-tall atrium. This sanctuary is wrapped in solid steel columns and etched glass that casts sharply patterned shadows on the slate floor and massive plaster walls. The plaster is velvety and perfectly finished, seams align in all dimensions, and a chair should be provided for the sensitive Canadian visitor to cry. Maki’s building is far beyond our contemporary norms.

Circulation spaces are arranged around the 10m-tall glazed atrium The interior smoothness pulls you along a black line of lights etched high above, past the gift shop and cafe towards the lit courtyard cube. Two square mashrabiya screens of zinc cast in the same pattern as the courtyard glass jut out from the second floor. Around the courtyard are a ticket desk, a small ceramics gallery, entrances to the auditorium and permanent galleries, and stairs to the second floor. There is a separate entrance with a driveway for school buses around the back. The auditorium lobby is a narrow rectangle with an incongruous white origami staircase in glossy marble, steel and terrazzo against a bright blue wall. This tacky intrusion looks like it would lead up to a VIP room and it does. There is another in the south-west corner above the cafe, with a nice view over the entrance. This prominence of private spaces seems to be a trend where cultural institutions now offer cocktails with a view of ordinary people queuing below. The 350-seat auditorium itself is a marvel, a geometric fantasy in teak that rises to a tessellated white dome. The museum rewards progress through spaces of subtly different but cohesive proportionality, all with astonishing detailing. The temporary galleries on the second floor have paired honeycomb skylights, the electric focus of which suggests Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum. It’s a shame these rooms have to be filled with anything. The first is darker, in order to display more sensitive, older works, while the second will hold contemporary exhibitions. This room overlooks the permanent galleries through a delicate glass balustrade that should produce interesting contrasts as objects below are seen between contemporary works above. The museum comes with a collection of about 1,000 objects, with a quarter on view at a time. A ceramics gallery on the ground floor will be free to the public.

A staircase in marble, steel and terrazzo leads up to a VIP room Both Maki and Correa have previous experience of designing Islamic centres. Correa won the 1997 competition for the AKDN funded Museum of Islamic Arts in Doha and was passed over by Qatar for the never-built design by the runner-up, Rasem Badran. Maki has served on the Aga Khan Award jury and recently designed the Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat in Ottawa, which opened in 2008. The two buildings in Toronto both appear to reference the Delegation, which is faced in fused glass instead of stone. Its dome peeks out behind the roofline and hides a large inner courtyard, both tactics that Maki repeats in Toronto, while Correa’s spectacular prayer hall improves on the Delegation building’s similarly double-layered dome. Where Maki kept the upper and lower layers symmetrical, Correa has offset the lower one. The roof in Ottawa is sober, light and tense like a sail, while Correa’s in Toronto is a feat of hazy mineral construction. Joining double-glazing on the outside and triple-glazing on the inside with a truss in between required a test assembly of the entire roof in Germany. It gives the prayer hall dome a remarkable meditative quality; a sense of movement and of the sky invited in.

Honeycomb skylights filter light into the second-floor galleries Correa’s plan has the graphic appeal of a composition by Malevich, but it is confusing on the ground. He redesigned the centre after it was moved to its new location on the enlarged site, keeping the principles of a circular prayer hall with a prominent roof (originally a metal pyramid) and curvilinear walls, which now form a sweeping and wasteful entrance facade. The centre always oriented towards Mecca while the museum was aligned at an angle so its entrance frames the prayer hall dome. The centre’s driveway is covered by a fussy lasagne of laminated timber, steel and glass at full height so that snow can blow under it, but once that’s past, the interior is luxurious; maple and marble, well built, and flooded with light. Yet its lovely rooms could be in different buildings. The social hall, prayer hall and its antechamber, handsome classrooms and a richly wooded library all exit to the same incomprehensibly scaled lobby.

The pattern on the glass walls is derived from an eight-pointed star There are even pull-out walls to separate concurrent activities, but empty, it is bizarre after the clarity of the museum, which I am reminded “is the real story here”. Standing in the garden facing the centre’s towering glass dome with the qibla below and no entrance to be seen, Correa’s building appears to hesitate between private conveniences and a public gesture. Religious organisations have always made arrangements for themselves, but Ismaili Centres are unusual in their dual purpose as diplomatic and religious buildings. What is the standard for a community building that claims to be both public and private? And when its neighbour powerfully and unpretentiously asserts its public status like the museum does? It must be hard to build next to Maki. The gardens remain to be filled out and grown in. Despite the investment in mature trees the first winter killed a surprising number; it will be years before Djurovic’s design is really finished, which is a reminder that we judge buildings too quickly. Djurovic created a refined outdoor place and though he can’t invent a deeper relation between the two buildings, a decade may bring out the mystery in the centre and the sensitivity of the museum. Whether the complex accomplishes its goal of increased dialogue depends on the people who run it. It always does. |

||