|

Nicholas Grimshaw designed Herman Miller’s grade II-listed factory in Bath to reflect the manufacturer’s philosophy of open, inclusive and democratic working spaces that can be chopped and changed to suit their purpose – ideas that have revolutionised the modern workplace over the past half a century This article was first published in Icon’s May 2014 issue: Factories, under the headline “Action factory”. Buy old issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this The Herman Miller factory, in an industrial estate on the outskirts of Bath, sits on the north bank of the River Avon behind a screen of weeping willows. In their shade is a series of circular outdoor tables and stools on which workers are taking smoking breaks. The Wood Mill building, built in 1976-7 and designed by Nicholas Grimshaw in the days of his partnership with Terry Farrell, stands out from the drab breezeblock and corrugated iron structures that surround it. With its tinted glass, louvered windows and cream-coloured panels, which echo the local Bath stone, it is a building firmly of its time – its stocky rectangularity and rounded edges evoke Italian plastic furniture from the 1960s. “We built it to be flexible,” Grimshaw tells me. “The fibre-glass panels have been repainted once, but it has stood the test of time. It was an architecture that doesn’t just stand there and you try to use it, but architecture that you can manipulate and change. It was all about the idea of democracy in the workplace.” Last year, the factory was grade II-listed – it is considered to be an early and important example of the British high-tech movement. The US furniture-maker – based in Chicago and famous for its classics of industrial design by George Nelson, Isamu Noguchi, Charles and Ray Eames and Robert Propst – wanted a fully flexible building that reflected the avant-garde design solutions it was pioneering in the late 1960s. Herman Miller’s Action Office System had revolutionised the American workplace by providing a kit with which an open plan office could be easily configured using mobile division panels. “We all bought Herman Miller furniture,” Grimshaw says of his emerging generation of new British architects, who all benefited from the fluid workspaces they engendered. Herman Miller’s managing director Max De Pree opened the architectural competition for a British factory with a short, forward-thinking brief that Grimshaw described in 1995 as “practically a poem”. He called for a building that “Encourages an open community and fortuitous encounter … Is open to surprise. Is comfortable with conflict. Has flexibility, is non precious and non-monumental.” Grimshaw, who saw off entries from Norman Foster and Jim Stirling to win the job, called his completed building an “Action Factory”. “We put a lot of thought into the services,” he tells me. They run the length of the factory ceiling, which is painted bright yellow, in two arteries that are accessible via gantries. The industrial machines, which are being constantly updated and repositioned to maximise efficiency of workflow, can be moved around the factory floor and plugged into these veins at any point. Similarly, the external panels and windows can be easily reconfigured within the grid of the steel frame. There were bays, for example, on three sides of the building, but when these alcoves became amphitheatres for local drunks, they were easily eliminated – only the entrance now scallops in this way. In 1980, after his split with Farrell, Grimshaw designed a distribution centre for Herman Miller in nearby Chippenham, known as the Blue Building, and he has created several other similarly high-tech industrial facilities including factories for Rolls-Royce in Sussex and Vitra Furniture in Germany.

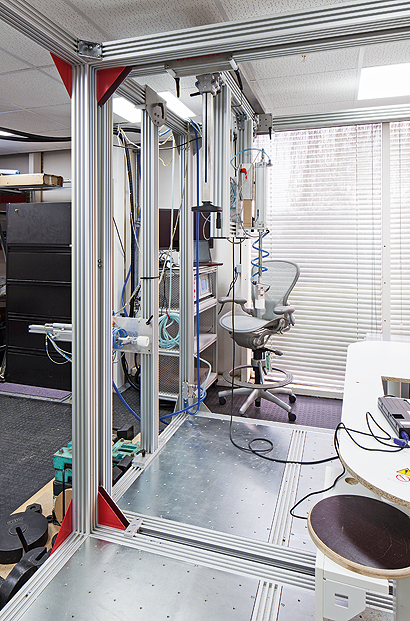

The services are accessible via yellow gantries In contrast to the bucolic setting, inside the Action Factory there is a smell of wood dust, burning plastic and glue. Earplugs are distributed to guard against the noise of the sawing and pneumatic machines. The 25 employees on the factory floor are clad in yellow DayGlo jackets and, with their reflective banding, wrap around shades and luminous ear protectors complete with radio antennae, they resemble worker bees. The head of UK manufacturing Charles Winn-Jones talks me through the heavily automated process. Three 40ft lorry loads of chipboard arrive every week, and much of the factory floor is given over to towering stacks of the material. They are arranged in batches of different finishes to be made into specific products and lifted using mechanical arms, called palimatics, on the end of which are huge suction devices. The factory is divided into cells whose machines perform different functions: in one, the boards are jigsawed into shape; in another they are almost seamlessly edged using laser technology. The workplace is surprisingly dust-free, the result of the whirring extraction fans that transport all waste to a large silo behind the plant. Hourly charts monitor the pace of production: 700 units are produced a day, one coming off the assembly line roughly every 40 seconds. Most of the products made here are the work surfaces, carcases and screen dividers used in what Herman Miller calls the Living Office. Whereas the 1968 Action Office used a small vocabulary of elements to create different environments (which are still manufactured in small quantities so as to fulfil 25-year continuity agreements), resulting in a fixed geometry, the Living Office allows you to create bespoke work spaces out of a narrow range of products. Industrial Facility, for example, created Locale for the brand, which comprises a vertical spine, to which shelves, cantilevered desks and tables can be easily attached. Hecht told Icon that the system enabled workers to fashion their own office spaces rather than “feeling like they are fitting into the employer’s or designer’s system”. Products designed by Yves Behar and Studio 7.5 are also made here. The options team sits on computers in an adjoining office, processing these customised orders. Above them is the research and development team, a top secret laboratory in which we are forbidden to take photos. It is a messy, creative space filled with miniature models of chairs. Various iterations of Behar’s Sayl Chair decorate a shelf and a prototype of Amanda Levete’s stainless steel and leather chair, which was shortlisted to furnish Wilkinson Eyre’s new reading room at the Bodleian Library, is placed in a corner, rather incongruously next to a life-sized sculpture of an Icelandic sheep. In a model shop, full of lathes and milling machines, development studio lead Stefan Kogut is sanding off miniature chairs designed by a Clerkenwell-based studio and produced on the office’s 3D printer. Someone is drilling holes by hand in a vacuum-formed sheet of plastic to which a paper template has been glued. Metal chair legs have been sprayed different shades and there is a special rig in which prototypes are being strength and fatigue-tested. Nick Savage, international product development manager for the brand, tells me that each product goes through two to three years of development. Grimshaw is about to break ground on a new Action Factory in Melksham, further up the Avon, where Herman Miller will consolidate the two sites over which it is currently divided, bringing manufacturing, logistics and product design under one roof (with no loss of jobs). With its gunmetal-grey facade and pillbox windows, it looks almost military in renders. The 15,000sq m building is designed around three elements: distribution and manufacturing dominate the L-shaped plan, in the crux of which is a triangular “people’s pod” that contains staff amenities and the main entrance. “We wanted to design a project which would contribute an aesthetic and human value to the landscape; an environment that welcomes all and encourages an open community,” Grimshaw explains, echoing Max De Pree’s 1970s brief. “The plan brings key travel paths as close as possible to the building entrances, allowing visitors to enter the heart of the building to see an active manufacturing and assembly factory, while keeping staff from feeling as though they are on show.” It is hoped that the move to the new facility will increase efficiency and speed the product development cycle. Wood Mill will then be put up for sale, which made its recent listing by English Heritage all the more urgent.

Reels of edging tape in different finishes

A test rig in the factory’s development studio |

Words Christopher Turner

Photographs Peter Guenzel |

|

|