|

|

||

|

The area in and around Basel in Switzerland is a veritable archive of Herzog & de Meuron buildings. From the practice’s earliest house conversions to its recent deconstructed office block for pharmaceuticals company Actelion (Icon 102), it is evident that the clients of its hometown have treated the firm well. Recently completed is its renovation of the Museum der Kulturen, in the very centre of Basel’s old town -– and it is an essay on the firm’s intelligent, inquisitive architectural style. The material Herzog & de Meuron had to work with was a 1849 neoclassical building, which was extended in 1917, but was still in dire need of more space. The building was accessed from the same entrance as the neighbouring natural history museum – the renovation provided the opportunity to change this and assert a separate identity for the cultural museum. This was achieved by opening up the courtyard to the back of the building to create a new entrance that is directly connected to the historic central square, and by building a feature roof above the existing structure.

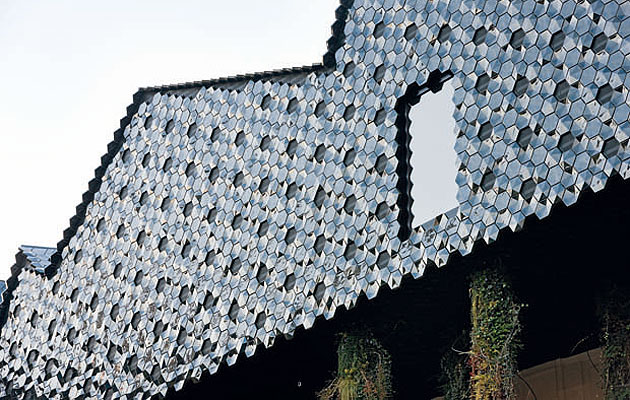

Jacques Herzog has said that “there are underground connections between different [H & de M] projects”, and here this is both literally and strategically true. The courtyard has been remodelled to slope downwards towards the building, and a glazed entrance storey that is far shallower than the piano nobile above has been created. The architect says these changes “lend the courtyard direction and give the building a face”. This strategy can also be seen in Herzog & de Meuron’s CaixaForum gallery in Madrid (2003-08), which has a similarly raised neoclassical block; at the entrance to the Tate Modern in London (2000); and in its famous house in Leymen in France (1997). The tactic gives familiar structures an uncanny, top-heavy appearance -– one of several defamiliarisation effects with which Herzog & de Meuron frequently experiments. Inside, much of the renovation has been simple, although typically clever. Windows on the first floor have been opened up, while on the second and third floors they have mainly been filled in, contributing to the sense of floating heaviness. Most spaces have been pared down to a minimum, while one room has had a floor removed to create a double-height space that can accommodate large objects and helps orient visitors within the museum. The roof is the most exuberant of the works. Its sawtooth profile, generated by an irregular, folded, plate steel structure, creates a column-free interior space – like a little cousin to Zaha Hadid’s recent Glasgow Riverside Museum (Icon 098). It is cantilevered out over the courtyard and odd, steel trellises carrying climbing plants are suspended from its overhang. The skin is clad in deep green, hexagonal ceramic tiles, many of which are pointed to catch the light, giving the surface depth and shimmer. This lushness echoes other Herzog & de Meuron investigations into material and texture, such as its Forum 2004 building in Barcelona, but when seen against its surroundings, the allusions to the typical tiled roofs of the old town become clear – an example of Herzog’s stated desire “to somehow be between the different poles of figuration and abstraction”. |

Image Iwan Baan

Words Douglas Murphy |

|

|

||

|

|

||