Based in Folkestone but with global ambitions, this new furniture brand is bringing its own sustainable approach to design and manufacturing, with a collection of cool but functional pieces

Photography by Robert Foster

Photography by Robert Foster

Words by Dominic Lutyens

Contemporary British furniture could be more exciting and experimental than it currently is. It could also be far more rigorous in its commitment to sustainability. These two views underpin the philosophy of DEKA, a new furniture and homeware brand. For now, its products are manufactured in its factories in Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire, which helps to reduce its carbon footprint.

Yet it has global ambitions and, consistent with DEKA’s eco agenda, plans to find local manufacturers in any foreign countries its products are sold in. Nurturing young British design talent is another of DEKA’s key aims, say its co-founders Steve Lewis and Lucy Abraham, husband and wife and business partners.

‘Our main markets now are the UK and Ireland, then we will probably expand in nearby European countries, such as Germany and France, and later in North America,’ says Lewis. DEKA has a sister company called The Collective, a specialist in sustainable acoustics systems, which was founded by Abraham in 2014.

It only works with brands that wholeheartedly embrace sustainability. Founded in 2020, DEKA, whose HQ is in Folkestone, Kent was originally called Design Kartel before it was rebranded, its two words conflated to create a snappier moniker. The company’s team took advantage of the challenging time during Covid to establish its identity and core values.

Photography by Robert Foster

Photography by Robert Foster

I met Lewis in DEKA’s London office at co-working space TOG in Shoreditch. Showing me some of its prototypes, he told me about his fledgling company’s ambitions. The actual pieces will be made of 100% recycled and recyclable plastic, 100% polypropylene, recyclable steel and FSC-certified wood, marble slab offcuts and agricultural waste, for example hay.

The company will also look into using cork, recycled fabrics and other sustainable materials. It’s set to launch its utilitarian, rather retro-looking DC chair, still at prototype stage and made of British timber and steel, in June 2023, and anticipates producing three to four pieces a year, designed in-house or by freelancers.

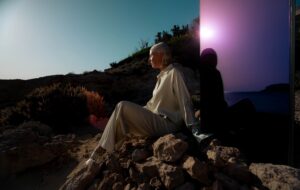

As a teaser to its imminent launch, the brand has published a large-format newspaper simply fronted by its name in a chunky, sans-serif font designed by branding agency Bonnevier Ainsworth. The images, which convey the spirit of the brand in a suggestive, abstract way, show examples of DEKA’s furniture, which is cool, funky and functional rather than glitzy and high-end. The idea is that the furniture, which will be sold via DEKA’s website and at several shops, will be accessible not expensive.

Archly shot with flash photography that gives them a flattened, modern look emphasised by sharp shadows, the images in the newspaper showcase the furniture in no-frills domestic or industrial settings. The images recall 1990s style magazine photography – think fashion snappers Juergen Teller or Corinne Day who worked for the ultra-hip style glossy of the day, The Face.

Photography by Robert Foster

Photography by Robert Foster

There are also images of a sunset in a city, creating a mellow vibe, a Weimaraner standing surreally on a coffee table, perhaps signifying unexpected outcomes and what look like stills of a disco scene in a 1970s movie.

The brand associates itself with words like ‘chaos’ and ‘outcast’ that recall 1970s punk’s anarchist stance, reflecting its desire to create ‘unconventional’ products that will make it ‘stand out from the crowd’. There’s also an image of an electric guitar being smashed, alluding perhaps to the guitar-destroying antics of Pete Townshend, who was inspired by the auto-destructive art of Gustav Metzger.

The Face, whose content straddled music, fashion and youth culture, seems an appropriate reference point for conveying another facet of DEKA’s ethos, in this case its cross-disciplinary character. ‘We want to have input from different genres, such as fashion,’ says Lewis. ‘We want to collaborate with graduates from various disciplines.’ DEKA aims in time to take on apprentices (The Collective already has an apprentice scheme).

Lewis believes that Britain’s furniture industry suffers from a lack of homegrown talent and DEKA aims to hire young British designers who, on graduating, traditionally find jobs abroad. His comment reminds me of the witty conceptual furniture by the likes of Gitta Gschwendtner and Carl Clerkin that made waves in the 1990s.

Photography by Robert Foster

Photography by Robert Foster

I find myself pondering that while there are plenty of talented UK-based furniture designers today, whether their work is as playful and original as that of their 90s antecedents. Lewis stresses that DEKA is independent. As such it isn’t beholden to shareholders, giving designers more freedom to experiment.

DEKA’s other eco credentials include using raw materials that are fully traceable at all stages of the supply chain in terms of their environmental impact, the ability to disassemble and reuse all products’ individual components and flat-packing goods during transportation and delivery to reduce fuel consumption.

Crucially, in its commitment to the circular economy, DEKA operates a system called ‘furniture return value’ whereby the company will buy products back from customers at a pre-arranged price and repair them to prolong their life cycle for as long as possible.

‘Companies often say that a product’s afterlife is the responsibility of the client, but we want to be accountable for all stages of its life cycle,’ concludes Lewis.

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter