|

All of life is here. Spintex Road, Accra, Ghana, is a six-and-a-half mile stretch of semi-industrial thoroughfare that runs from the Tetteh Quarshie Interchange (purportedly the largest in Africa) to the coastal port of Tema. At its start it is flanked on one side by the airport and on the other, for almost its entire length, the country’s only motorway (as yet), built by Kwame Nkrumah in the 1950s. The road was originally planned as a small, two-lane feeder route serving a handful of factories built outside the city’s residential zones, but today the suburbs that have sprung up along its length are among the fastest-growing in West Africa, part of a new phenomenon – the “urban corridor”, an uber-city that, in this case, takes the Ibadan-Lagos-Accra-Abidjan route and is home to some 25 million inhabitants. Clearly, two lanes won’t do. In May 2008, Ghana’s first Western-style shopping mall, the Accra Mall, was opened by Bentel Associates, a South African-Ghanaian consortium. It promised to bring a new “shopping experience” to the city, traditionally dominated by open-air markets, small shops and, more recently, American-style strip malls (though without the necessary car-parking provision). According to the developers, the Accra Mall is “one of the largest and most modern shopping malls in the whole of West Africa”. Given that there are only two such malls (one in Lagos and the other in Accra), the statement isn’t perhaps as hyperbolic as it sounds. While the arrival of the mall caused much excitement among Ghana’s small but growing middle classes, it has had other, possibly more interesting, repercussions, not least of which has been traffic. The entrance-exit to the Accra Mall runs directly off the Tetteh Quarshie Interchange and slap-bang into the Spintex Road. At the time of writing, the traffic congestion along the road has to be seen to be believed. It can take up to four hours to traverse its length, two of which can be spent negotiating the circumference of the roundabout that lies at its start. Although there are numerous shops, markets, kiosks and mini-malls along its length, the penultimate mile or so of the Spintex Road adjacent to the mall is particularly interesting because of the roadside market, a peculiarly West African phenomenon, which operates as traffic grinds to a halt. In November 2008, partly out of frustration (as I happen to live off the damned road), I began taking a closer look at the conditions that lie along it, from the retail to the residential, in the hope of finding questions (if not answers) that might prove useful in the ongoing battle to understand the nature, culture and direction of West African cities. A modest ambition, then. There are three major factors at work along Spintex – one, the average speed of traffic (just under two miles per hour); two, the burgeoning middle-class residential suburbs along its length that create both the commuter class and its chaos; and three, land ownership issues, which, while not exclusive to Spintex, have created a grey area of non-ownership along its sides, allowing a whole community of traders, producers and retailers to live, work and sell directly off the road. Despite the apparently chaotic appearance of Spintex, particularly in the hours between 6am and 6pm, there are three very distinct zones of operation in the half-mile strip between the secured edge of the runway and the motorway that flank the road at either end. Closest to the road and spilling into it in every conceivable direction is the retail strip, the market. Open-air, open-plan, mobile, flexible and seemingly arbitrary in its selection of goods, everything and anything you could possibly want is here – Christmas hampers, puppies, bicycles, Chinese-produced kente cloth, tombstones, second-hand books, toilet paper, the Bible and the Koran. Threaded in among the young men holding baby Rottweilers are the Big Brands; young men and women in brightly coloured red or yellow jackets who sell airtime and Coke. They are easy to spot.

Scenes from the Spintex Road, January to November 2009 Adjacent to the retail strip of random goods lies the second “zone” – production. Operating out of makeshift workshops (whose power supply is generally “creatively” engineered), hundreds of cane sofas, hampers, wardrobes, desks, garden gnomes and “traditional” masks are made each day. The output, given the rudimentary nature of manufacturing infrastructure, is staggering. Who buys plaster-cast storks or concrete Corinthian columns? Someone, clearly. Finally, sandwiched behind the production zone and sometimes in its midst lies the third layer of Spintex: residential. Not, I hasten to add, the gated, security-patrolled estates that have attracted up to half a million Ghanaian expatriates who’ve returned in the past decade or so and who contribute heavily to the cursed traffic flow, but the shack-like, temporary-except-they’re-permanent structures that house many of the traders, artisans and workers who ply the roadside market. There are huts, small child-care centres, food stalls, garden centres and security outfits all squeezed into the 20-odd yards that remain between the edge of production and the runway. It’s hard to guess – and harder to find out – exactly how many men, women and children live and work here, and hard to estimate the nature and depth of the social networks that such patterns have engendered. On what basis do people congregate together? Language? Ethnic group? Guild? Trade? Craft?

Scenes from the Spintex Road, January to November 2009 I struck up a very casual acquaintance with Millicent Koranteng, the co-owner of a small booth at the junction that leads to the suburb where I live. Together with her sister Constance, Millicent runs Millicoon Fast Tea. I asked Millicent what she thought of the Accra Mall. When we first began to talk, towards the end of 2008, she wasn’t sure what a mall was, or what it would be. She wondered if it would be for white people (and in that description she included Ghanaians who’d lived abroad, regardless of their actual skin colour – unwittingly, perhaps, she’d stumbled on a deeper truth about colour and culture than the one we routinely admit to). But by the time the mall was completed, she was under no such confusion. Millicent and Constance, along with several other traders who I’d come to recognise, if not know, were regular visitors to the mall. Many of the traders who ply the Spintex scrub up after a hard day’s roadside selling and, dressed in their Sunday best, creep in past the barrage of security guards and enter the mall’s hallowed grounds. They are easily recognisable; they look, admire and linger in the mall’s wide, air-conditioned corridors, but they never, ever enter a shop. These are not consumers-in-waiting, nor are they typical of the urban poor. Articulate, aggressive and ambitious, they navigate laterally across what the West calls the “informal economy” in order to create wealth. Within days of goods arriving in the mall directly from Durban, cheaper, Chinese copies are found along Spintex outside. Leftover and past-their-sell-by-date foodstuffs from Shoprite find their way onto the street the following morning. No sooner had Ghana’s first Apple store set up shop than knock-off iPhones began to appear. A week after Nike and Pippa’s Gym opened, I was offered a “tummy tuck” (a strange, quasi-scientific “machine” guaranteed to knock inches off one’s waistline) through my passenger window. Clearly, consumer patterns, habits and tastes are under observation, though perhaps not in the way one imagines and certainly with a lot less fuss. Forecasting, trend-casting and just-in-time delivery logistics have no place here – market women send representatives to the mall to buy entire lines in one go. Two days later, at the most marginal mark-ups imaginable, Truworth’s entire spring collection is on the street. It’s apparently pointless trying to work out how many size 12s, 14s or 16s a buyer may need – on Spintex, right next to the wooden kiosk that resells the clothes, a tailor has set up shop. For a small additional fee, he’ll cut to fit – right there, on the street, while you wait. At a conference in Delft a year ago, where I presented a paper on my findings along the Spintex Road, someone asked if what I purported to have uncovered was a useful representation or exploration of the larger cultural and social conditions that operate in Accra, or even in Africa as a whole. I’d certainly like to think so. Embedded within and along Spintex are many of the complex issues that Ghana (and, by extension, much of West Africa) faces – in terms of its relationship to modernity and the formation of a new urban culture that is neither a poor pastiche of the West nor hopelessly bogged down by the weight of its own traditions. The relationship between shopping and almost every aspect of contemporary culture is the subject of a much longer article, but as a point of departure, it’s not a bad place to start. Spintex Road offers a strange, often confusing, sometimes amusing glimpse into a way of operating that is at once problematic and yet full of possibility. There’s a new condition at play; a new way of working, living, making, selling that is both under-theorised and ill-understood. I remain (childishly) convinced that there are new conditions in front of us if we could only work out how to see them, what questions to ask. Derrida’s 1986 essay, “Where the Desire May Live”, points in a rather unexpected way to an architectural possibility that may be even more urgent for Africa than the “developed” West for whom, no doubt, the essay and its questions were originally intended. “How is it possible,” he asks, “to develop a new, inventive faculty that would allow the architect to use possibilities without aspiring to uniformity, without developing models for the whole world? An inventive faculty of architectural difference which would bring out new types of diversity … which would not be reduced to the technique of planning. There is a formless desire for a new location, new arcades, new corridors … new ways of living and of thinking.” New ways of living and thinking. No. Yes. Maybe. Spintex, it seems to me, isn’t a bad place to start.

One-metre-high “colon” figures – garden gnomes masquerading as policemen in colonial garb

One of the many “kente” weavers who have set up shop along Spintex

Links between home and the Ghanaian diaspora reflected in airline schedules

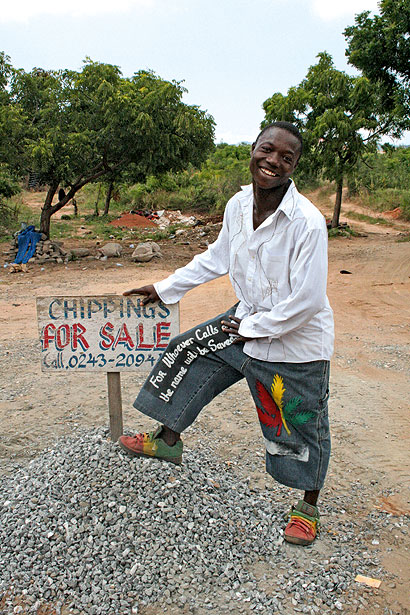

One of the small-scale production zones where granite is chipped to sell to contractors |

Image Lesley Lokko

Words Lesley Lokko |

|

|

||

|

Bookshelves and desks made by the roadside |

||