|

Bjarke Ingels is mad about The Wire. Thanks to the unending jet travel that comes with his new status as one of the world’s most in-demand young architects, he has at last finished watching all five seasons of the epic American crime drama. “It’s a total of 65 hours,” Ingels says, fizzing with enthusiasm, “but because I have regular transatlantic flights I’ve been able to dive into this universe. I think that the aeroplane cabin is a contemplative space that I would otherwise miss.” The question of whether Ingels enjoys travel comes up because it’s hard to tell when he’ll be spending any time on the ground for the next few years. His practice, Bjarke Ingels Group or BIG, has just scooped a run of enormous projects across the world. There’s the Danish pavilion for the 2010 Shanghai Expo in China, a national library for Kazakhstan, a city hall for Estonia’s capital Tallinn, and a huge project to turn a lifeless rock in the Caspian Sea into a new, sustainable city for Azerbaijan. At a time when many architects are struggling, BIG is thriving. The most recent win, announced a couple of days before we meet, is comparatively local, but still large: a women’s sports complex in the Swedish city of Malmö, a short drive from Ingels’ native Copenhagen. No wonder Ingels is tired. The night before we meet in a London cafe, he told a packed room at the Architecture Foundation about BIG’s contribution to December’s Shenzhen & Hong Kong Biennale, and after that he was up until 4am. But he’s unstoppable – every question triggers a long, lively, effortlessly articulate answer. Asked, for instance, if his time watching The Wire is just relaxation or if it has any value to his practice as an architect, Ingels’ response is instant, uplifting and coherent: “I really believe that architecture is not the goal but the tool – human life is what you want to maximise the potential for. And in many literal ways our prime source of inspiration is trying to observe how life in the city evolves, and how the framework that we create for it should adapt to this evolution.” Ingels’ quickfire eloquence – he delivered a lecture for the prestigious TED Talks series in July – drove his decision to publish a manifesto in comic book form, rather than dusty text. Yes is More, which came out in November, is a typical BIG product: popular, upbeat, fun, deliberately quirky, accessible and bullshit-free (reviewed in icon 077). “Architects tend to skip the text bit and flip to the page with the images, right?” Ingels says. “So we’re like sneaking the medicine into the pudding.” The medicine here is the “yes is more” philosophy that has driven BIG’s success. It’s a position of radical affirmation: a sort of super-pragmatism, an ideology without ideology, which suggests to architects that it’s possible to give everyone involved in a project exactly what they want and still come away with an uncompromised piece of architecture. Indeed, just the mention of the word “compromise” in connection with BIG’s approach sets Ingels off. “A compromise is where both parties are equally unhappy,” he says emphatically. “We try to make both parties 100 percent happy, and that … makes impossible some of the standard solutions, and it makes possible a sort of hybrid solution.” He gives the example of the Mountain Dwellings in Copenhagen, an apartment block completed with former partner Julien De Smedt in 2008 (icon 064). Through Ingels’ usual combination of intuitive leaps and programmatic jiggery-pokery, it integrates an enormous parking garage with 80 flats – and manages to give every unit a southern aspect and a garden. “Quite often it is not a compromise,” Ingels continues. “It is synthesis.” Mountains are a recurring feature of BIG’s architecture, with the studio favouring geological skylines and continuous surfaces, slopes, ramps and paths that wrap around, through and over buildings. The mammoth Zira Island masterplan in Azerbaijan calls for seven huge blocks modelled on seven of the country’s peaks, and the Eight House, a huge residential development nearing completion in Copenhagen, is based around a rollercoaster walkway in a figure eight. BIG’s output is also characterised by faceted blocks that look as if they’ve been whittled, perforated facades and volumes that have been twisted like optical illusions. Often these buildings look highly formalist, but as Yes is More explains, all are a product of Ingels’ process of “synthesis”. This pragmatism, and his gifts as a communicator, are traits that Ingels shares with his architectural mentor, Rem Koolhaas. “I started studying architecture the year that S,M,L,XL was published, so in a way I read Rem before I read Le Corbusier,” Ingels, 35, says. After finishing his studies in 1998, Ingels went to work at Koolhaas’ studio, OMA. It was a shock. “At the time I arrived there, I was convinced that OMA was like this cult where everyone had the same approach and was driven by the same ambition and understanding,” he recalls, “and that was so massively not the case … I sometimes thought I was the only one who had actually read any of the books, at least the words in them.” What had drawn Ingels to OMA was the clarity of the concepts the studio produced – he imagined that they were the result of a clear, orderly process, carefully directed by Koolhaas. Instead, it was anarchy. “Rem would never really give you the scheme, he would just demand that you come up with something,” Ingels says. “And as a result, of course, I think there was an incredible waste of effort … so much wasted effort and ambition discarded almost without conversation …” Wasteful or not, it worked, and Ingels runs BIG along similar lines. But before BIG came Plot, the studio that Ingels set up with another Koolhaas alumnus, Julien De Smedt, in 2001. Plot won acclaim for projects like the 2003 Copenhagen Harbour Bath and 2005’s VM Housing in Copenhagen – but it didn’t work out, and in 2006 the two partners went their separate ways, Ingels to found BIG, De Smedt to set up JDS Architects. What went wrong? Answering, Ingels becomes uncharacteristically hesitant. “In a way, I think it worked out quite well, in the sense that … we were around as Plot for five years, longer than most relationships, longer than any relationship I’ve had actually, and, er … through cell division it evolved into JDS and BIG. I think it was just time to move on.” This idea of evolution is central to Ingels’ thinking. It comes up half-a-dozen times in the interview, and the subtitle of Yes Is More is “An Archicomic on Architectural Evolution”. This was the inspiring quality he found at OMA, the one he drew on when establishing BIG’s way of working. “Normally as architects get success, the quality of their work gets diluted, because you have like one creative genius that hands out the assignments to executive morons, so the more people that need to be employed by the creative genius, the more diluted the work gets,” he says. But at OMA, the process was bottom-up, and merely “curated by an editor … you have 100 ideas from 100 people, so you have 10,000 ideas”. These ideas have to compete until only the best is left standing – the survival of the fittest. The same creative struggle now takes place within BIG, allowing it to handle its recent enormous growth – the practice now has five partners and employs 70 people, twice the number that were at OMA when Ingels started there in the late 1990s. But there are some differences with OMA – apparently when Koolhaas visited the BIG HQ during a trip to Copenhagen he disapproved of the jolliness of Ingels’ team. Ingels gives the impression that his time at OMA in Rotterdam wasn’t exactly fun. “My belief in starting BIG was that you could do this interesting work and still have a good time – it doesn’t have to be so … punitive.” Certainly Ingels is fun company – even at 10am, after a heavy night, he’s an electric conversationalist and popping with good humour. His relentless positivity and enthusiasm is bracing. It makes one wonder if “yes is more” is really a philosophy that can be exported, or if it’s reliant on Ingels’ charisma – that it might not be the ideas that succeed so much as the way he sells them. One BIG project that’s currently in the works is a maritime museum in a historic dry dock in the Danish city of Helsingør. The client is now being sued by the Danish architects association because BIG won the competition despite defying one of its rules: that the museum had to be contained within the dock. “Some people had asked if they could place some functions outside the dock and they had gotten a no,” Ingels says, amused. “We never ask questions, basically, because you might get a ‘no’, whereas it’s much better to propose a convincing project and then figure it out.” It’s a typically mischievous and counter-intuitive move by BIG, but it does imply that “yes is more” might be more about moving the client to suit the project rather than moving the project to suit the client. Ingels acknowledges this. “An architect, and this might sound negative, has to be capable of manipulating people as the sculptor is capable of manipulating material,” he explains. “Because that is essentially our building material – it’s getting other people to go along. But also there’s a lot of incorporating input from the outside – I realise that there’s this like entourage of decision makers and if you can, in a zen-like way, make their forces the driving force of a project, you’re much more powerful as an architect.” Listening to Ingels talk in this way about the people-management involved in BIG’s work, one can see why Darwin might appeal to him. Whether it’s talking about The Wire or the interplay of desires in a large mixed-use project, he can sound like a sort of naturalist, examining human systems from above, proposing structures to bring them together. In this, he sees architects picking up where evolution left off – we used to adapt to suit our surroundings, and now architects adapt our surroundings to suit us. Ingels says: “So really observing how life happens and evolves is one of the primary jobs of an architect – to make sure that we actually create buildings that fit the way we live.” And he smiles broadly, and you have to smile along with him.

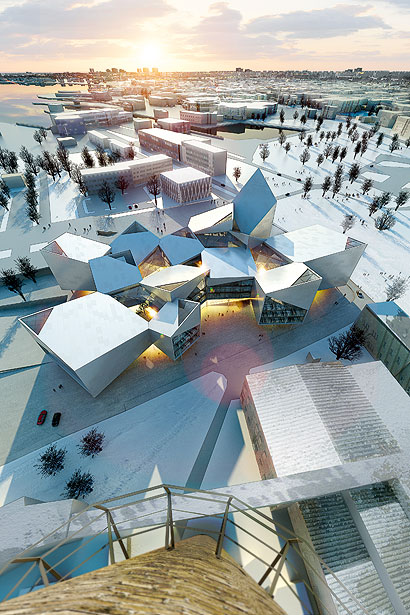

Tallinn Town Hall, Estonia, due 2013 |

Image Mark Guthrie

Words William Wiles |

|

|