words Daniel Miller

The wired generation unplugs long enough to spend some time on the couch in this fascinating insight into electronic culture, writes Daniel Miller.

How are new technologies altering our understanding of ourselves? What new attitudes are being formed by their use? And how is the new media changing our personal relationships? Many gallons of ink and billions of pixels have been spilled discussing the electronic revolution. But there has been surprisingly little discussion of the more personal sides of the issue.

An exception to this pattern is found in the work of Sherry Turkle. A psychologically trained sociologist with a peculiar insight into the world of machines, Turkle has been looking at the “intimate ethnography” of the digital age more or less since it began. In June 1984, Turkle’s path-breaking book The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit came out one month before William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer gave us the word “cyberspace”. Now, Turkle is a professor at MIT and founding director of the research initiative “Technology and Self”.

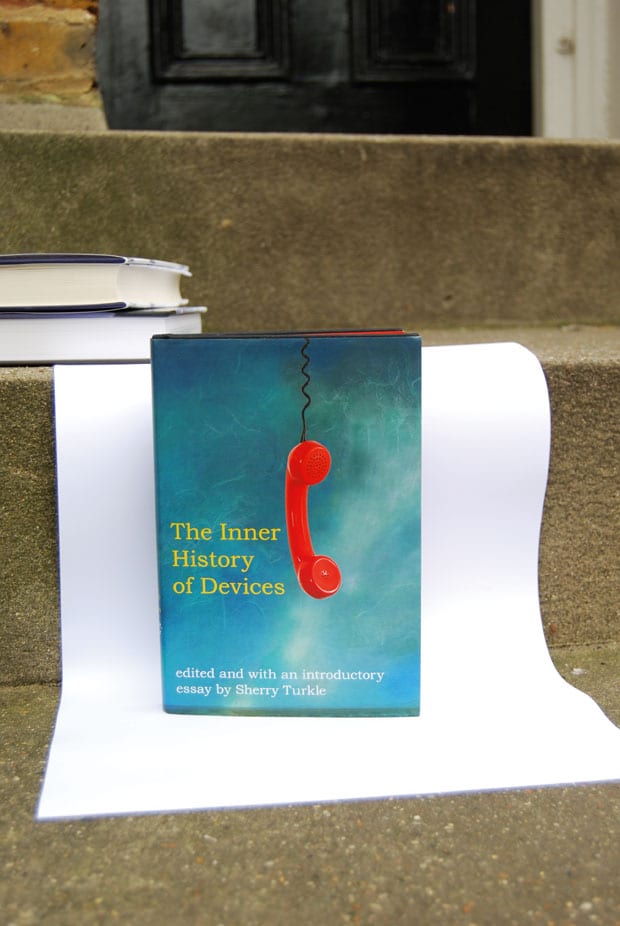

Her most recent book, The Inner History of Devices, is drawn from that initiative, representing the last in a three-volume series that Turkle has edited based on her seminars. All three volumes are grounded on a common hypothesis: that objects condition our interpreted world and embroil themselves in our intrigues. But while the first two in the series, Evocative Objects and Falling for Science, focused on everyday and conceptual objects respectively, with The Inner History of Devices Turkle returns to her roots in computer technology.

The book is divided into three sections. The first gathers personal memoirs on topics including cell phones and prosthetic eyes. The third presents anthropological fieldwork, including a lucid essay on video poker by Natasha Schüll and an informative study of tech news site Slashdot.org by Anita Say Chan.

But the spine of this book is to be found in its second section, which supplies three remarkable briefings from clinical practice. “I work with internet characters much the way a child therapist works with toy dolls,” writes the psychiatrist John Hamilton in his contribution “The World Wide Web.” His colleagues are equally savvy and radical. In her essay “Computer Games”, psychoanalyst Marsha H Levy-Warren notes that she has begun conducting parts of her sessions through email, and describes the results as productive.

Meanwhile in “Cyberplaces” Harvard Medical School Associate Professor Kimberlyn Leary defines psychoanalysis in cyberpunk terms, as an interface between the “hardware” of the consulting room and the “software” of emotions. These technological tropes are not just metaphors. “Cyberspace,” Leary points out, “creates new classes of imagination and subjective activity. The question of what is ‘real’ and what is ‘fantasy’ [and] the question of when such a distinction should matter … has become newly relevant to the culture at large.”

The Inner History of Devices charts this new terrain with an admirable depth and maturity, and supplies a thoughtful inquiry into our fast-changing world.

The Inner History of Devices, edited by Sherry Turkle, MIT Press, £16.95, mitpress.mit.edu