words William Wiles

Benedikt Taschen is going to sell the moon. Bits of it, anyway – later this year he’ll be bringing out a book that includes fragments of lunar meteorite. For now, however, the 47-year-old publisher is in London for the opening of the first Taschen shop in the UK, on the King’s Road in Chelsea, opposite the new Saatchi Gallery.

With its prime location, golden Philippe Starck display cases and open volumes of the glossy, large-format art books Taschen is famous for, it is luxurious for a bookshop. But Taschen’s company, not yet 30 years old, is remarkable for having revolutionised both ends of the publishing spectrum. No one has done so much to democratise architectural publishing, selling monographs at a price the mass market is happy to pay. At the same time, the company is the Dubai of the literary landscape, unveiling landmark after landmark apparently for the sheer joy of breaking records and exhausting superlatives for the largest, the most expensive, the most exclusive.

Taschen has just launched a couple of grand architectural projects: a major monograph of Jean Nouvel, with a plexiglass slipcase designed by the Pritzker prize-winner, and a total reprint of the first ten years of Arts & Architecture, a seminal American magazine of the mid-20th century. It’s the A&A reprint that we’re particularly interested in. Under the editorship of John Entenza, Arts & Architecture was an influential force in championing the West Coast modernism of architects such as Richard Neutra, Charles Eames and John Lautner. The magazine was a significant architectural patron, through the celebrated Case Study programme that produced gems including the 1949 Eames House, as well as a standard-setter in graphic design.

“I love this mid-century architecture and design,” Taschen says of the project when we talk in a restaurant near the new store. He brims with enthusiasm on the subject. “I just love this stuff. It took years to get all of the issues together. It was easy to get 90 per cent, and very complicated to get 95 per cent and super complicated to get the last remaining copies. It was a small, tiny print job, you know, but then it was highly influential all over the world. I love it, it’s something I’m really passionate about.”

Taschen has made a career out of his enthusiasms. An avid collector of comic books, he opened a comic shop in his home town of Cologne in 1980, when he was still a teenager. In 1983, he bought a stock of 40,000 remaindered books about Dutch surrealist painter Rene Magritte, and resold them for a tasty profit, a move that convinced him that there was more money in art books than there was in comics. Rather than buying more remainders, he began to commission his own, starting with an edition on Dalí. By 1988 titles on architecture and furniture design were added to the range. Now, the Basic Architecture range of monographs contains dozens of full-colour books for £5.99 each. Architectural publishers have been forced to compete. “Others, including us, have had to copy them,” says the editorial director of one UK architectural publisher, who adds that a title that they sold at £30 20 years ago couldn’t be sold at the same price today, thanks to Taschen.

But the Arts & Architecture reprint is anything but cheap. This instalment, covering the years 1945 to 1954, comes in ten boxes and weighs in at £400. It joins, at the same price, the Nouvel monograph and other architectural publishing landmarks such as the company’s 2006 reprint of seven decades of Domus magazine. Another project, with Frank Gehry, is also in the works, again with a custom cover. These exclusive, high-end publishing projects are the source of much of Taschen’s publicity and prestige. Together with the high-volume, low-margin £5.99 range, these books have transformed the image of architecture publishing from a stuffy, expensive specialist field into something accessible, popular, desirable, even sexy. The £400 event-books might not be accessible, but they feed the star-status of architecture’s premiere league, lend lustre to the Taschen brand, and make architecture publishing glamorous.

“Architects, they are very restrained in their emotions and this is reflected in how architecture books most of the times look like,” Taschen says. “They are always trying not to do too much and to be on the safe ground.” He helped change this, prioritising the entertainment value of the books, and simultaneously liberating his architect collaborators to be freer in their thinking. “From the beginning, he had his own ideas about how to do the book,” Taschen says of working with Jean Nouvel, “and after a while I said, why don’t you just do it [yourself]. And so in his case it’s a real artist’s book, and we tried to assist him to develop his ideas but it’s entirely his own project.”

The opportunity to collaborate with architects, designers, artists, photographers and other cultural figures including Ingmar Bergman, Muhammad Ali and a variety of porn stars, appears to be what Taschen thrives on. Speaking admiringly of the great architects he’s worked with, he says: “All these people are crazy, of course.” Crazy? “That’s how they work, if they were normal, no one would care about their work,” he explains. “Of course it is out of the normal range, that is how they are capable of doing what they are doing.”

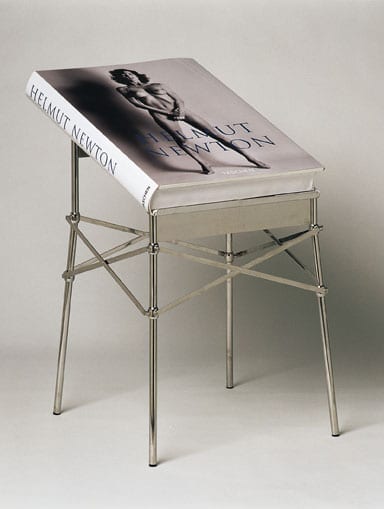

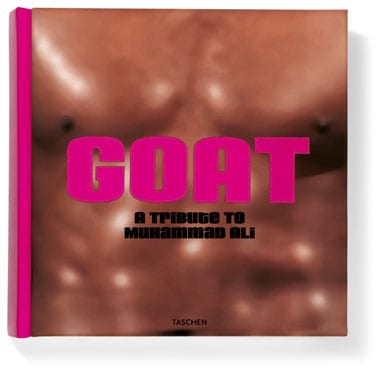

Taschen’s collaborations have produced some extraordinary publishing megaprojects. In 1999 he published SUMO, a retrospective of the work of photographer Helmut Newton. This beast was the largest book produced in the 20th century: 50cm by 70cm; the Vatican’s bible binder had to be called in to help make it. It came with its own stand, designed by Philippe Starck. Although the 10,000 copies of SUMO sold at a mere £6,000 each, edition number one (signed by 80 celebrities) later sold at auction for $304,000 – the most expensive book produced in the 20th century. SUMO provoked another round of catch-up from Taschen’s competitors, who suddenly broke out in a rash of gigantism, and whetted the publisher’s appetite for more. In 2003 he followed up SUMO with GOAT, subtitled Greatest of All Time: A Tribute to Muhammad Ali, the Champ’s Edition of which cost £7,500 – allegedly the second most expensive retail price in publishing history. It came with a set of photographs, a silk-covered box and a limited-edition artwork by Jeff Koons.

And, on the horizon, there’s the moon-rock project: a reprint of A Fire on the Moon, Norman Mailer’s 1970 book about the Apollo Moon landings. Mailer’s text will be larded with contemporary photographs, and that’s not all. “The whole design comes in a box that you can put on the wall,” Taschen says, enthusiasm racing again. “It was done by Marc Newson and there is also a special edition of the last 25 that come with a lunar rock.”

Do these inclusions and special features have any genuine merit, or are they just publishing “bling”, meant to generate desirability and exclusivity? Taschen argues that, for instance, the inclusion of a filmstrip in the company’s recent Ingmar Bergman retrospective gives the reader a genuine insight into the book’s subject. Fair enough, but the idea that the buyer of a special-edition monograph about Ingmar Bergman would have so little clue as to the mechanics of film production is questionable. There’s also an economic motive – less lavish, higher-volume editions for the general public are supported by the high margins and massive publicity that the special editions generate.

But Taschen’s image as a publisher is bound up with picture-led glossiness. Significantly, that first art book that Taschen sold, the remaindered Magritte, was in English – but still sold out in Germany. Was there another lesson in it – that text isn’t really important, and the economics are in fact based on pictures, production value and price? Do people actually read Taschen books? “We are not just doing illustrated books, but on the other hand we are not just a fiction or non-fiction publisher,” he says, mulling the point. “The text is of course equally important.” For the prestige editions, that might be true, but at the high-volume end of the market it’s a safe bet that the text isn’t what people are buying.

That’s something Taschen almost acknowledges with his next remark, which he adds with a mischievous smile. “If people read it all, that’s a different question. But that’s not our problem. And the ones who do read these books should not be disappointed.”

What Taschen’s “special features” point to is a consistent desire to push at what the idea of a book should be. In the early days of the business, the company experimented with selling unlikely products including kimonos, cardboard skeletons and inflatable gorillas. It kicked at received ideas of what publishers should “publish” and what bookshops should sell. But this is not a sign that he finds publishing restrictive. Talking about the much-promised rise of e-books, he becomes passionate on the indispensable value of the book as an aesthetic object. He is expanding the boundaries of the book, reinforcing it as an artifact, not just a store of information. “For us it’s about art, and art is an object of desire to create,” he says. “I have no concerns at all that books will last forever.”

Portrait by Steve Double