The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, by Mass Design Group

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, by Mass Design Group

Today’s memorials are less about quiet contemplation of the past than direct confrontation with the present, finds Jacoba Urist

Today, artists and architects are designing conceptually bold proposals for monuments at a faster rate than any other moment in modern history. This spring, Boston plans to announce the winner of a contest for an outdoor artwork commemorating Martin Luther King Jr and Coretta Scott King, who met and fell in love in the city as students. The finalists amount to a roll call of leading voices from the worlds of art and design: from Yinka Shonibare and Adam Pendleton to Adjaye Associates and Mass Design Group, who submitted a collaboration with Hank Willis Thomas.

Today’s monuments express a human craving for a concrete place to validate loss that stretches back to time immemorial. Although absence is near-impossible to represent through design, the impulse to memorialise tragedy through a display of remembrance is perhaps one of the most basic human aesthetic instincts.

In January, for example, a memorial service was held in Japan’s Kobe East Park to commemorate the 24th anniversary of the great Hanshin earthquake, which claimed 6,434 lives. In a poignant act, those who gathered lit 5,000 bamboo lanterns that together revealed a series of hiragana letters spelling out ‘tsunagu’, which means ‘to connect’.

Unlike its neo-classical and monolithic predecessors – such as the statues lining Richmond, Virginia’s Monument Avenue – the contemporary memorial is as much about what we have forgotten as what we remember. It enumerates stories that our history books have neglected or calls to attention the second-class citizenship handed to some of our communities.

Artist Patricia Cronin’s three-tonne marble Memorial to a Marriage is a likeness of herself and now-wife, painter Deborah Kass, in a serene, postcoital embrace. In 2000, when Cronin created the memorial, gay couples had more limited rights. Gay Americans could draft healthcare proxies for end-of-life decisions, but they could not formalise their lives together in the eyes of the law.

In the style of 19th-century mortuary sculpture, Memorial to a Marriage, unveiled to the public in 2002, channels the tradition of white, static statuary to critique social structure. Cronin purchased her own burial plot in New York’s Woodlawn Cemetery to house the artwork, which remains on public view today as a poignant reminder of the shameful gap in social justice.

Memorials hold such power to elicit emotion that it is of little surprise that communities feel vested in the way in which designers commemorate their loved ones and articulate their cultural narratives. Equally, it appears inevitable that anger will result when a monument is perceived to miss the mark.

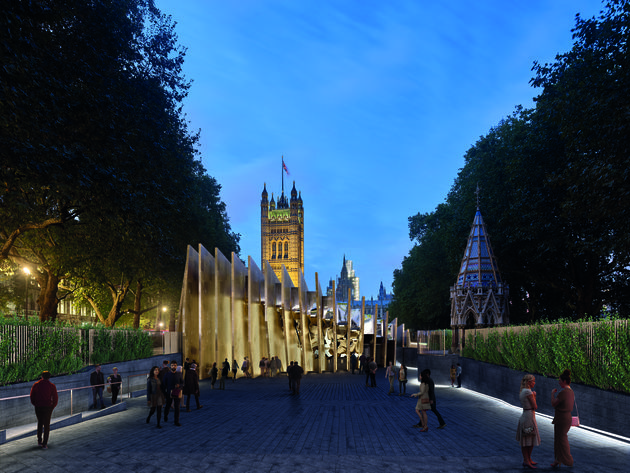

David Adjaye and Ron Arad’s joint proposal for a Holocaust Memorial and subterranean learning centre near Parliament in London was subject to protest in 2018 for failing to directly reference the Holocaust in a way that segments of the British Jewish community feel is appropriate. Selected by an international jury in 2017, the proposal is for a structure in the form of 23 tall bronze fins, arrayed in the southern part of Victoria Tower Gardens by the Thames. Using negative form to express unspeakable absence, the space between each dorsal ridge is intended to represent the 22 countries where Jewish communities were destroyed.

David Adjaye and Ron Arad’s proposed design for the National Holocaust Memorial in London

David Adjaye and Ron Arad’s proposed design for the National Holocaust Memorial in London

Adjaye has defended the proposal on the basis that Britain needs this design to remind us of what happened and ensure that Holocaust deniers are confronted with reality. When done well, memorials shape our perception of past events and jog our conscience. A Holocaust memorial near Parliament would serve as a rebuke to a government slow to recognise the resurgence of the far-right in recent years and how genocide can result from victimising minority groups. The location responds to the re-emergence of antisemitism in Britain and Europe, not to mention the Holocaust denial expressed across social media.

Unquestionably, Adjaye’s design is meant to speak truth to power. Now that we are 70 years post-Second World War and few Holocaust survivors will actually see it come to fruition, the monument is far less about grieving than it is a warning to resist bigotry and racism, particularly in a time when Holocaust denial worryingly persists.

Adjaye and Arad’s sculpture sheds light on the challenges of designing contemporary monuments in an aesthetic that has become the dominant language of memorial – a minimal fusion that traces its lineage to classic styles – while absorbing the work of pioneering modernists like Donald Judd and Robert Smithson. The language of minimalism can often spark a stronger emotional response than other public art genres, for instance in the case of Peter Eisenman’s 2005 Holocaust memorial in Berlin, which disorients us and challenges our very notion of space.

Eisenman’s monument is considered a modern classic, which overcomes an individual and national collapse of compassion. With no marked entrance or exit, thousands of rectangular concrete slabs, forming a blanket of nearly five acres, appear to undulate across the sloping land. New York architect Eisenman contends with the unfathomable through abstraction— how else does one render this scale of human barbarity?— and manages to generate the seeds of a perpetual, existential guilt.

What Eisenman designed is an exquisite piece of public art in its own right, a concrete necropolis, in which individuals become active participants in the creation of memory. Within this massive sculptural maze, the space encourages visitors to experience a helplessness that bears witness to the atrocity.

Like the Holocaust memorial planned for London with a learning centre attached, Berlin’s monument has a formal, underground trove of educational information. Even so, it has raised tricky questions about memorial-making by positing minimalism as the unofficial lexicon of contemporary memorials.

Social media boasts plenty of folks experiencing Eisenman’s vision on their own terms, notably collected in Berlin-based Israeli artist Shahak Shapira’s graphic online project, Yolocaust. On Instagram, we see tourists strike yoga poses and take selfies amid the concrete blocks. Shapira’s site Photoshopped the lighthearted figures from these social media posts into stomach-turning historical images of the realities of the Holocaust. While it wasn’t Eisenman’s intention to enable this kind of flippant or disrespectful response from visitors, one can’t help wonder if certain contemporary memorials are tapping into a collective experience that is far from introspective, and dependent, superficially, on external validation.

Is anger a more constructive public emotion? In her book, Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America, Erica Doss illustrates how the proliferation of memorials across the US underscores a cultural obsession with historical memory and a desire to stake those issues in very public places. ‘Contemporary memorials are very much about producing an emotional response,’ explains Doss, an American studies professor at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana.

A monument in Montgomery, Alabama harnesses anger in a productive manner. Opened last spring, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice is an immense, unyielding installation on a green hill in the Deep South that relies as much on design prowess as it does copious research. Some 805 rusted corten steel boxes are suspended from the ceiling of an open pavilion – akin to dangling, limp bodies. Each is inscribed with names of lynching victims, one casket-coffer for each US county where they were murdered. The Washington Post has called it the most effective memorial in a generation.

Raise up by Hank Willis Thomas is among the sculptures at the Montgomery memorial. Photo via Hank Willis Thomas studio / Equal Justice Initiative

Raise up by Hank Willis Thomas is among the sculptures at the Montgomery memorial. Photo via Hank Willis Thomas studio / Equal Justice Initiative

Built by the legal advocacy group Equal Justice Initiative and Boston-based, non-profit Mass Design Group, each of the boxes has a corresponding steel column, which sits outside the main building, awaiting collection by the county for whom it has been forged. The intention of the designers is that counties come and reclaim their monument, to construct a memorial to racial terrorism in their own communities, thereby keeping the history present and remembering its victims. Bryan Stevenson, an acclaimed public interest lawyer and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, has issued far more than a symbolic ultimatum. Lynchings included town square hanging, torture and dismemberment. The monument compels the counties to take public ownership of and reckon with their past.

This memorial isn’t designed to comfort or heal. It is built to cast a long shadow and issue a challenge, according to James E Young, who has authored several books on memorials and served on commissions for Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial and the September 11 Memorial design competition. The implication for counties who refuse the offer is clear: in doing nothing, they whitewash history. ‘This memory is meant to oppress,’ he says. ‘And it does so brilliantly by creating a devastating, upside-down hanging forest, rooted not in the earth, but in the heavens above.’

Created with contributions from artists Dana King, Kwame Akoto-Bamfo and Hank Willis Thomas, the six-acre site includes outdoor artwork which recasts slavery, racial terror and police violence in the US on a much wider social continuum. In this manner, racially motivated lynching becomes part of a longer, ongoing story. Thomas’s Raise Up, a row of bronze, life-sized depictions of men with arms held aloft, draws inspiration from a 1967 image by South African photojournalist Ernest Cole of a string of naked black miners, strip-searched during a medical exam. But visitors are likely to interpret the work as representing black men— Hands Up, Don’t Shoot— in contemporary America. And the artist welcomes multiple interpretations.

The Montgomery memorial again raises the question of how 21st Century monuments are consumed, in an age when many will experience them through photographs on social media. Photography is allowed thrughout the grounds. But an essay published last December by author William C Anderson reflected on the commodification of Jim Crow violence (that is violence effectively condoned by the Jim Crow laws which imposed racial segregation in the US) for some white spectators of lynching, through the use of photography. When visitors use their smartphones at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, he argues, they reproduce, intentionally or not, the opportunity for white onlookers to engage in the spectacle.

In Montgomery, we find a minimal monolithic monument at the centre of a constellation of different approaches, also including Dana King’s diminutive and dignified female statues, dedicated to the women who led the historic Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Artist Thomas points to the monolith as a stark reminder of forgotten violence, while saying his is more ‘narrative’. Yet both are part of one whole: ‘My sculpture is a small part of this larger sculpture, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which functions I think as a conceptual piece of art,’ says Thomas.

It is a signal, at least, that there is space for far more than the minimal memorial. Indeed, in our hope of us being shaken once again by the terrible violence of the past, the makers of memorials employ whatever means available, in the faith that our generation will learn from what they have built.

This article originally appeared in Icon 190, the April 2019 edition that looked at memory, memorials and architecture