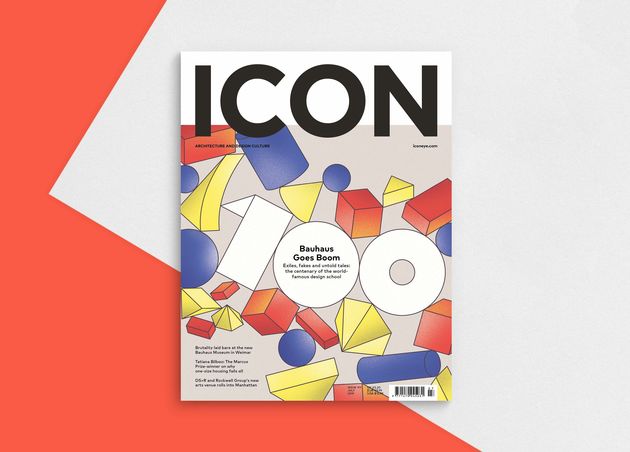

We celebrate the centenary of the design school with a look at the lesser known impact it had globally and its surprising relationship with Expressionism

The July issue looks at the influence of the Bauhaus globally, from its origins in Weimar to the surprising impact it had in Israel and the Soviet Union. Plus: our reviews of the Shed and the Design Museum’s Kubrick exhibition, an interview with Sheila Hicks and our Bauhaus Icon of the Month.

A word from Priya Khanchandani, editor of Icon:

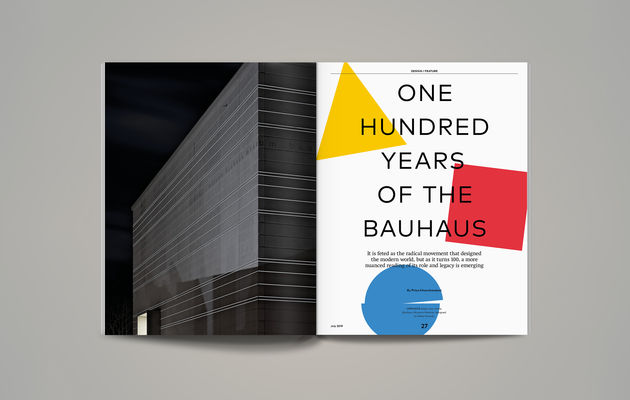

There are few modern design movements in Euro-American history that have stood the test of time like the Bauhaus. For a design movement, more so than for most other historic events, a centenary celebration of such magnitude is a major accomplishment.

At the same time, the Bauhaus history factory is churning out echoes and fakes by the dozen. There are worthwhile ventures such as the new museums at Weimar and Dessau and the extension to the existing archive in Berlin. But there will always be those who jump on the bandwagon, in this case with products that purportedly hark back to a school that redesigned the world.

A hundred years on from the spring in 1919 when Walter Gropius set up the first Bauhaus school in Weimar, Bauhaus history is often appropriated uncritically. It is understood in black and white: as the school that gave rise to a trailblazing eponymous movement; one that changed our understanding of modernity by fusing design with fine art, craft and technology. None of this is untrue; it is simply that there is more to be said.

The accomplishments of Gropius, Mies and Breuer in the US are often reported, but less so are stories of those of who moved to another enormous land, the USSR. In this issue, Owen Hatherley brings to light the work of those who have fallen into obscurity despite redesigning entire cities of the Soviet industrial heartland.

Israeli architect and architectural historian Zvi Efrat reflects on the ‘Zionist Bauhaus’ of Tel Aviv, where the whitewashed walls of the White City have been preserved thanks to the canonisation of vernacular modernism and the label ‘Bauhaus’ having been applied to what was arguably a pastiche of architectural styles.

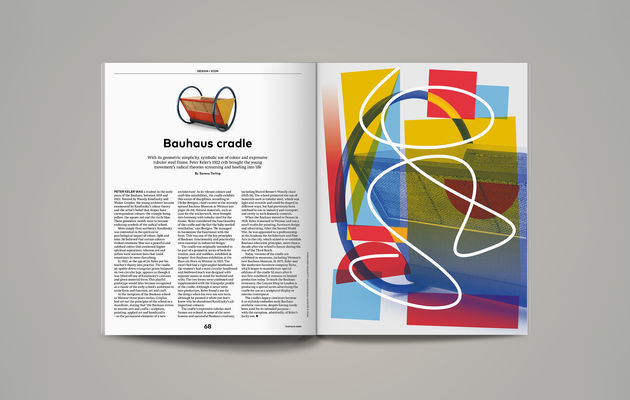

In addition to such real and contested legacies, we consider how contemporary design has moved on. Emerging studio Morph, whose expressionistic use of material and multi-media work sits at the boundary between physical and digital, embodies a postmodern hybridity that is the antithesis of Bauhaus simplicity.

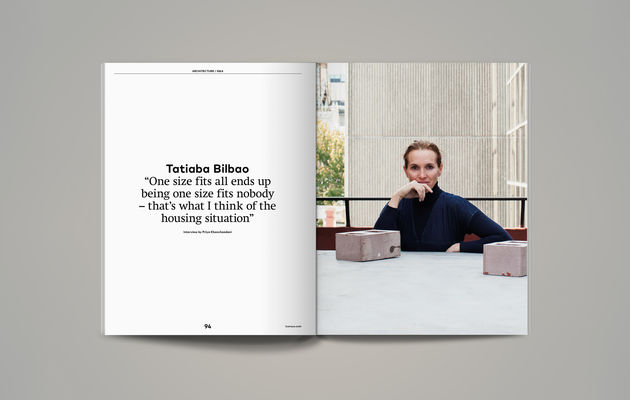

Mexican architect Tatiana Bilbao reveals her concern with functionality but also with the fact that we are living, breathing beings that exist within an organic context. Quite contrary to the Bauhaus ideal of mass production, she reflects: ‘One size fits all ends up being one size fits none.

Subscribe to Icon magazine to be the first to get the new issue!