The Wicker Man includes an effigy of a ram’s head, which the train passes through in a burst of flames

The Wicker Man includes an effigy of a ram’s head, which the train passes through in a burst of flames

As the UK’s first new wooden roller coaster in two decades takes its inaugural plunge, a new generation of thrill-seekers can enjoy the sculptural majesty – and slightly terrifying quirks – of the king of the fairground. Priya Khanchandani went for a ride

The train ascends. With every click it is hoisted further upwards into grey-white skies. After what feels like an eternity, it reaches a climax. On either side the treetops shake. We begin to go gently over the edge, like sticky ice cream trickling off a cone. A tentative rider, I hold on to the safety bar, as though that will help us stay put. Before I know it, we are in unstoppable free-fall.  The Wicker Man is Alton Towers’ newest addition

The Wicker Man is Alton Towers’ newest addition

We are hurled downwards, then over a series of three smaller hills. At each gradient an iota of uncertainty sets in. Will we touch down? Are we going to make it all the way? Before long, we pass through darkness and arrive at the other side. There is light. We get off, exhilarated. We meander out into the rain, readjusting our balance to the omniscience of gravity. Moments later, we are amused by the terror on our faces in the gift-shop photos.

The Wicker Man is Britain’s first new wooden roller coaster in 22 years. Merlin – the company that dominates the country’s amusement park market, owning both Alton Towers and Thorpe Park – has until now only commissioned steel roller coasters. This state of affairs irked wooden roller coaster evangelists. Andy Hine, chairman of the Roller Coaster Society of Great Britain, has been campaigning for a wooden coaster to be built in the UK for the past two decades. ‘A steel roller coaster can look like you’ve given a child a crayon, told them to scribble on a page, and then they just created that in a track,’ he explains, ‘whereas a wooden roller coaster with its woodwork structure is much more artistic. And the ride is much more challenging. At the end of it you want to have another go because it promotes a different emotion in your body, more outright fun than scary thrills.’

Hine’s campaign involved an annual event at Alton Towers called Loopathon and another known as Pegamania, during which his members would put wooden pegs on the name badges of each member of staff as a reminder to management that steel rides weren’t the only way. While a niche sect in the UK, the Roller Coaster Society’s school of thought finds greater support in the US, where wooden roller coasters have always been taken as seriously as their steel counterparts.

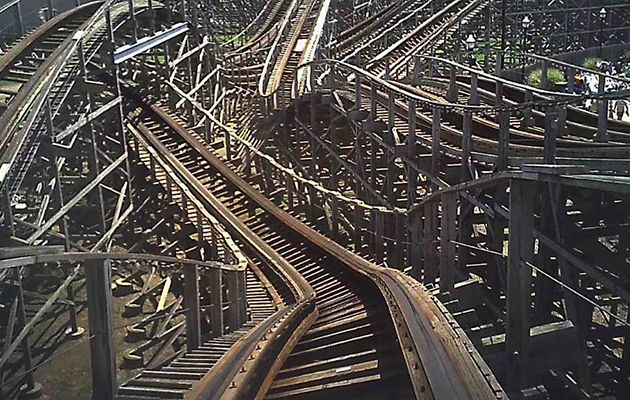

These titans of roller coaster history are worth taking seriously. Their distinctive sculptural quality cannot be easily wrought from metal. The lattice structure of the Wicker Man ride comprises layer upon layer of complex wooden trusses in uniform horizontal, vertical and diagonal sweeps. These scaffold the leaps and loops, giddy ascents and perilous falls, of its track. The largest turn, which descends from the first peak, is held up by a series of stilts attached to the ground that form an elegant (and, as a piece of design, virtuosic) sweeping curve: features absent from steel coasters, which do not need the same physical support.

Wooden rollercoasters can often match their steel counterparts in scale and ambition

Wooden rollercoasters can often match their steel counterparts in scale and ambition

Yet despite the extra support, wooden roller coasters match their steel counterparts in scale and ambition. The Wicker Man comprises 618m of sprawling track. Its centrepiece is a 17m sculpture topped with a flame-spurting ram’s head. The company that designed it, Great Coasters International (GCI), has been responsible for more monstrous rides in the US. The Beast, at Kings Island in Ohio, is the longest wooden coaster in the world at 2,243m, while Lightning Racer, at Hersheypark, Pennsylvania, is a wooden ‘duelling’ roller coaster that allows two trains to ride simultaneously. Meanwhile Swiss company Intamin created the 1,700m White Cyclone, completed in 1994 (currently closed for works), and the 1,600m Jupiter, opened in 1992, both located in Japan.

Wooden roller coasters aren’t necessarily any less exciting to experience, either. Riding a wooden roller coaster is a bit like going on a runaway train, only much faster – and much more thrilling. I have never experienced a steel ride that matches the sensation that you are in free-fall, while the bumpiness adds to the feeling of uncertainty. ‘Wooden coasters,’ says Hine, ‘have more shake, rattle and roll!’  Megafobia in Oakwood Park, Wales, built in 1996

Megafobia in Oakwood Park, Wales, built in 1996

There is always an element of unpredictability with a wooden roller coaster. According to mechanical engineer James Swinden of GCI, the way in which the wood adapts to its environment changes the experience of the ride. ‘When you ride a wooden roller coaster in different seasons, it will feel a little different,’ he explains, ‘since in a drier season you will sense the bumps a little more. In a wetter season, which at Alton [Towers] will be the majority of the time, the wood will swell and the track gauge will be tighter: it’ll be a smoother ride.’ The wood that was chosen, Southern Yellow Pine, only expands or contracts a fraction of a centimetre at a time and no more than 3mm, ensuring that the ride is still stable and robust. ‘When you ride the roller coaster you can hear it clicking along the tiny gaps,’ Swinden says.

The earliest roller coasters, which form the basis for the wooden coasters of today, developed from rides known as switchback railways. These were designed to parody the movement of a train crossing the hills and valleys of a varied terrain. Among the earliest of these opened in 1884 at Coney Island in New York. Rem Koolhaas featured it in his retrospective urban manifesto Delirious New York (1979): ‘Whole train loads of people tear up and down its slopes with such violence,’ he wrote, ‘that they undergo the magic sensation of lift-off at its peaks.’

More than 30 coasters were built at Coney Island between then and the 1930s. These included the Cyclone, which with 2,640ft of track and 12 drops, remains an important precedent in wooden roller coaster history. Completed in 1927, it was an icon of the machine age, the contemporary of the modern skyscraper and the limousine, the vacuum cleaner and washing machine. In this golden era of amusement parks the coaster was the king of all rides.

But it didn’t last long. A majority of American amusement parks were forced to close in the wake of the Wall Street Crash and the Great Depression. They were only revived with the advent of Disney in the 1950s. By then, faster, smoother steel roller coasters were being engineered. Two schools of thought on roller coaster design emerged: those who advocated high-speed steel rides and those who favoured the wooden roller coasters of an earlier era.

Before the Wicker Man opened in March, there were only a handful of wooden coasters in the UK. Blackpool Pleasure Beach boasts no fewer than four, all of which date from the 1930s and remain fully functional; the Scenic Railway at Dreamland in Margate first ran in 1920. These testify to the robustness of wood as a material for fabrication, even if enthusiasts would argue that these don’t reflect the modern capability of wood as a medium for a thrilling ride in the way that The Wicker Man and its contemporaries do.

Although the Wicker Man benefits from modern engineering and is a pioneer within its genre, it is not as extreme as the other wooden roller coasters made by GCI. This is partly because of the strict planning restrictions to which Alton Towers is subject, which requires all rides to remain below the tree line so that they don’t interrupt views of the countryside that surrounds it. Earlier plans filed with Staffordshire Moorlands District Council in 2003 for a giant wooden roller coaster with a 60m drop were rejected on grounds of noise and height.

To work within the limits, GCI created a three-hill sequence in the first drop, which gets you from the highest to the lowest part of the ride, instead of a single huge descent. ‘Normally we don’t have a restriction on height,’ says Swinden. ‘With this, we have a lot of low sweeping curves and stayed close to the ground.’ The result is more family-friendly than the park’s most extreme rides, including Nemesis, Oblivion and The Smiler.

The allure of the Wicker Man in an amusement park dominated by more hardcore roller coasters is its crafted quality. While it benefits from modern engineering and technology, as a designed object it contrasts with the svelte futurism of neighbouring rides. The latticed trusses that hold it up look like a giant, rhythmic weave – appropriate given the folkloric derivation of its name and the narrative around the ride, which begins in a dark room where you are told you are about to be sacrificed in a pagan ritual. The rustic atmosphere is reinforced when the train enters the mouth of the ram’s-head effigy to a burst of smoky flame.

Lightning Racer Tracks in Hersheypark, where two trains ‘race’ in entwining wooden structures

Lightning Racer Tracks in Hersheypark, where two trains ‘race’ in entwining wooden structures

The familiarity of wood and the fact that it derives from a once-living organism makes it an attractive material. Perhaps more so in an age of 3D printing and endless forms of synthetic polymer, where materials can be produced in a laboratory. We are surrounded by substances that are both far removed from nature and often unfriendly towards it. The unique grain of each piece of wood provides a refreshing antidote to a world of standardisation and mass production.

Such complexities are evident in the sculptural essence of the Wicker Man, beyond its experience as a ride. Nostalgic though it may be, the vernacular appearance of each truss of Southern Yellow Pine brings the technology and modern engineering of the ride back down to earth, rendering it warm and relatable. And the character traits of wood stand firm beyond the theme park. With Nendo having launched Fritz Hansen’s first entirely wooden chair in 61 years this year at Milan’s Salone del Mobile and the international resurgence of interest in timber architecture, wood is as irresistible a material for contemporary design as ever.