|

|

||

|

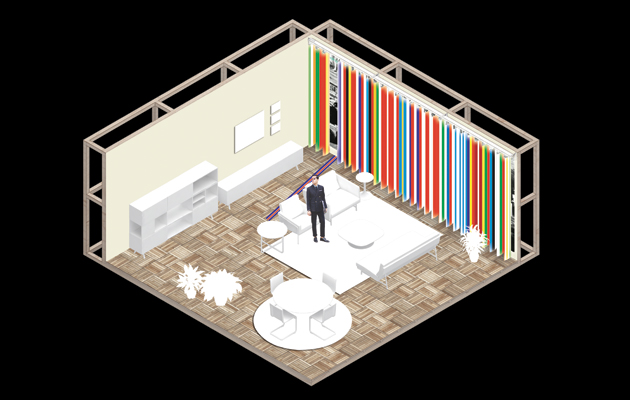

The Dutch architecture practice is designing a Brexit installation for the opening of London’s Design Museum. Partner-in-charge Reinier de Graaf reflects on how the practice’s engagement and views have evolved since its first EU barcode flag in 2001 We invented the EU barcode some 15 years ago: an alternative, colourful symbol for the European Union. A symbol of optimism. The idea was that the EU could be fun. In 2016, that spirit seems hard to maintain. Britain decided to jump ship, sparking similar discussions in the Netherlands, France and Austria: whether the interests of individual nations would be better served when ‘free’ to pursue their individual course, unimpeded by interference from Brussels. That national sovereignty needs to be preserved and restored to its former absolute state seems to be the sentiment of many. This installation tells a different story. It shows a simple living room: the type you could find in any European home, including Britain. The everyday objects in the room – table, chairs, sofa – have their origins in various European countries. In total there are 28 items – one from each EU member state – which together constitute the room’s interior, making it a showroom of European design and inadvertently of European collaboration. Vertical blinds, reflecting the colours of the EU barcode, control the amount of light and ensure privacy. Invented and patented in the US in the 1950s (around the same time that the European project started), vertical blinds have been applied all across Europe as one of the cheapest and most effective ways of window covering, and one of the most common forms of sun-screening. Common in interiors from Sweden to Italy, from Ireland to Greece, vertical blinds have become the silent witnesses of an emerging European unity. The system isn’t perfect: the connection between the slat and the pivoting head, from which the slat hangs on to the mechanism, is fragile and often breaks or disconnects. In this room, it is the slat that carries the colours of the Union Jack that has broken off, leaving an opening through which we see the daunting remnants of Europe’s historic past.

OMA’s original barcode (top), which unites all the flags of the EU countries, and a version that’s missing the Union Jack (above) In the context of overheated debates, bloated anti-European rhetoric and the media frenzy that follows, this simple room serves as understated evidence that there is a European project no matter what, which exists and continues despite recent setbacks. European integration is a fact of life, which transcends short-term performance indicators and constitutes an essential vehicle that gives us our security, comfort and all the other wonderful certainties we tend to take for granted. In a world where the most pressing issues inevitably exceed the size of nations, interdependence between nations is a given. Brexit does nothing to change that. More than just a political phenomenon, Europe is a form of modernisation, or rather a chance for the political sphere to catch up with modernisation. Interdependence between nations is a direct result of scientific and technological progress: once unleashed it cannot be reversed. When problems escalate, so must the arena in which they are addressed. An institution like the EU is born out of the knowledge that, in the face of the bigger issues, we are all minorities. Countries in Europe have a choice: they can either realise or ignore the fact they are small. Yet small they all are, including Britain. The United Kingdom is a modern nation, the origin of the Industrial Revolution, former centre of a global empire and, largely as a consequence, currently home to a global community. More than any other European country, Britain has been affected by other cultures. A retreat within the confines of its own borders is not only anti-European or anti-modern, but ultimately un-British. This living room offers ample proof. The Design Museum opens on 24 November 2016. This is an article from Icon’s upcoming issue – Icon 161 – in which Edwin Heathcote writes about architecture’s failed approach to housing and Ian Lowey looks back to the 1960s psychedelic revolution. Subscribe to Icon for all that and more

Behind the vertical blinds, a film will look at the history of European integration in reverse |

Words Reinier de Graaf

Above: The living room contains furniture sourced from the EU’s 28 member states |

|

|

||